The Uses of Value Research in Marketing

The term "value" has many meanings. In market research we meet the term most often in the phrase "value for money" but also in the notion "consumer values". The latter is our concern here. Values in this sense are the consumers’ priorities in their living. Values are something broader than attitudes and opinions; they are also more consistent than opinions and more lasting than attitudes. A full definition of (cultural) values thus reads: Values are generalised, relatively enduring and consistent priorities for how we want to live. Our values unite us with certain people, products, and services and estrange us from others.

Markets, technically speaking, are continual exchanges of property rights until they end up with those who pay an optimum price. One ultimate driving force of the markets in a region is the values held by its population. Values indicate priorities for how we want to live, and, in our type of society, the market is the major system through which we can realise our values.

Such simple considerations have suggested that it may be very fruitful to incorporate value research into market research. Value research has many benefits for marketing.

| Value research can give you information about the segments where your product is strong and weak. Since long, such information has been available in terms of demographics, i.e. age, sex, region, income, et cetera, the very staples of market research. In many instances, however, persons of the same, age, sex, and income go for different products and services because they have different priorities. Then demographics need be supplemented by "valuegraphics". | |

| Value research tells you how your product or service is positioned in relation to the competition. Cognitive maps of markets can be constructed in several ways. They show brand names and their distance from one another. Close distance means close competition, far distance means safe segmentation for the brands. One of the most efficient types of cognitive maps is constructed in terms of consumer values. Such maps are easy for executives and brand managers to interpret. | |

| Value research shows you where there is room for a new product or service. Some areas of a market map may be white; here there is room for a new product or service. By reading the value co-ordinates of the white space we find out which qualities are desirable and which ones should be highlighted in information about the new offering. | |

| Value research can assist you to the optimal choice of distribution channels. People with different values tend to shop in different places. Products with known appeal to specific value groups should receive extra promotion in the type of retail outlets that attract these value groups. | |

| Value research is helpful in media selection for public relations and advertising. The public’s choice of media, be they print or broadcast, is strongly influenced by values. Some advanced national guides of media selection have in the 1990s begun to include information on value groups of the readers and viewers. | |

| Value research can guide the shape of your advertising. It is well known that demographic market information bores advertising agencies. Value information seems more exciting, and is indeed helpful in both copy writing and finding illustrations and background to the messages. |

In Europe there are several market research houses that can count regular and systematic value research since the 1970s, for example Basisresearch GmbH in Frankfurt, Cofremca in Paris, DemoSCOPE Marktforschungsinstitut AG in Bern, and Sifo AB in Stockholm. The trend started in the USA with the Yankelovich Monitor in the late 1960s. In 1973 Elisabeth Nelson of Taylor Nelson Ltd. in London introduced a version of this value monitor in Europe. At about the same time, and without knowledge of the Yankelovich effort, Alan de Vulpian of Cofremca started regular value measurements in France. Today there is actually more knowledge about value measurements in market research than in academic research. Some comprehensive value surveys by university researchers are, of course, essential such as the work of Pierre Bourdieu (1979), Ronald Inglehart (1990) and the European Values Study initiated by Jan Kerkhof of Louvain University (Barker, Halman & Vlot 1993). However, they lack the regularity of the commercial surveys and cannot easily establish value trends. Some are theoretically and methodologically advanced but of less substantive interest since they are based on student samples (Schwartz 1992) or employees in a multinational corporation (Hofstede 1980).

There are a variety of commercial models for value studies in marketing. A brief critical review counted some 15 different systems of value segmentation of markets. (Sampson 1992). Many are closer to personality profiles than values, and some mix demographics into their typologies. They usually use proprietary methods.

We will distinguish the theory-based systems of value measurements from the ad hoc systems.

Theory-Based Systems of Value Measurement

Academic value research has been conducted in the liberal arts as history of mentalities, in philosophy and theology as analysis of world religions (e.g. Morris 1942), in anthropology as a part of the study of culture (e.g. Douglas 1982, Kluckhohn & Stodtbeck 1961). In sociology value research has a longer tradition (e.g. Sorokin 1937-1941). In recent political science we also find value research (e.g. Inglehart 1990). There are many contributions from social psychology (e.g. Rokeach 1968, Schwartz & Bilsky 1987, 1990) and from traditional psychology (e.g. Edwards 1954). Psychologists have also been very active in the neighbouring field of psychographics with a focus on personality traits rather than values. We lack a review of value research in marketing of the kind that is available for psychographics in market research (Gunter & Furnham 1992).

An Illustration from Psychological Theory

A major contribution to value research in marketing has come from developmental psychology. There are stages of growth from psychological immaturity to a rich and full adult life. The modern inspiration of a scientific study of this type of value change comes mainly from Erik H Erikson, David McClelland, and, above all Abraham H Maslow. Arnold Mitchell gave this research tradition a reinterpretation. The result was the Values and Life Styles Program (with the brand name VALS) of the Stanford Research Institute, later named SRI so that it would not be confused with Stanford University. We will cite VALS here as a first example of a theory-based system of value measurement.

The main contribution of the VALS team is the thesis that there are two parallel paths to ego development, one Outer Directed and One Inner Directed.

Figure 1. The Two Paths to Value Maturity according to VALS

The left arrow of psychological development is the traditional, outer-directed hierarchical path, described also by Maslow. The right arrow is the more contemporary inner-directed, heterarchical path. (This distinction is not consistent with Riesman’s (1953) more well known usage of similar terms.)

The basic division is between three categories: the Need-Driven, the Outer-Directed, and the Inner-Directed. The first category acts because of needs rather than choice. The last two categories can choose between acting upon external cues or internal cues. One brief and simple example of the major types: The Need-Driven person may lose weight because he or she is too poor to get enough nutrition. The Outer-Directed may loose weight because it makes him or her look better to others. The Inner-Directed may loose weight because it makes him or her feel better.

Everyone starts his or her psychological development with a primacy of basic biological needs of physical security and of basic emotional needs of trust and belonging. Those retaining these priorities also in adulthood are called Need-Driven. Among Post-Belongers there are two alternative options. Those who give priority to their need of esteem are called Outer-Directed. Mitchell divides those whose adult priorities are the need for esteem into two levels, the Emulators and Achievers.

The other route concerns self-development. Those who put their priorities here are called Inner-Directed. The Mitchell team distinguishes between three levels of self-development here: I-Am-Me, Experiential, and Societally Conscious.

At the top of both paths, Mitchell places a small number of exceptional individuals who are able to successfully balance all phases and priorities, the Integrated. Not everyone reaches this level. On the routes from childhood to maturity different people rest at different levels and continue to exhibit the values of their final levels.

The VALS system is based on well-defined categories and an underlying dynamic theory. In the late 1970s and early 1980s it became widely used in marketing and advertising research, mostly in the United States. Its usage has declined in recent years, but its approach of basing the measurement of values on a theory is sound.

An Illustration from Sociological Theory

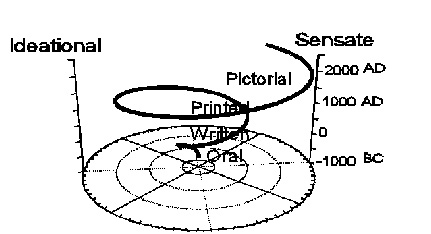

In the 1930s the Russian-American sociologist Pitirim A. Sorokin, classified the history of ideas using a scale that ranged from sensate culture to ideational culture. In a sensate culture most symbols have a clear, close reference to the evidence of the senses or refer to gestalts of biological and physical existence. In an ideational culture most symbols and cultural expressions are removed from the external sensory data and gestalts of everyday experience, and mainly allude to other symbols or internal states.

Sorokin’s work, Social and Cultural Dynamics shows how Western civilisation has fluctuated between sensate and ideational cultures. An ideational culture in 600 BC had changed into a sensate culture by the time the Roman Empire was at its height. This, in turn, developed into a new ideational culture in the Middle Ages, which was followed by the sensate culture of our times.

The main forces behind the shifts in cultural mentality are immanent, i.e. residing in the symbol-system (culture) itself. In a great lurch towards ideational culture, the symbol-system loses touch with everyday realities and a sensate mode gets a new opportunity. In a lurch toward sensateness the symbol system loses touch with spiritual reality and the ideational mode gets a new chance. And so on. The pattern of historical value change is "lurch and learn", as also Daniel Yankelovich (1997) has observed.

There may, however, also be external forces behind the swings. In a comely but imperfect coincidence with Sorokin’s main cycle, Marshall McLuhan (1962) also finds turning points in the cultural development at about the third or fourth century before Christ, the mid-fifteenth century, and at the time of the late twentieth century. McLuhan’s criterion for change is the vehicle by means of which the important symbols travel: oral prior to Plato, written until the end of the Middle Ages, printed until the mid-twentieth century, and pictorial (or electronic) in our days. The medium, he argues, affects the message: the values of oral culture are those of wisdom, the values of written culture, on the other hand, are those of knowledge and information. The use of the medium of printed text is harsh and manly, and drives forward instrumental tasks, while the values of pictorial culture are soft and womanly, using the intimate medium of television to express internal states, evoke emotions, maintain harmony and well-being. The latter are the values of our times, and we see their appeal in the advertising and packaging of modern products and services.

Figure 2. Ideational and Sensate Values and Media Technology

In an ideational culture, ethics is concerned with unconditional moral principles. In a sensate culture ethics is concerned with the pursuit of happiness. The former thus preaches value fidelity, the latter preaches pragmatism. In a sensate culture human activity is extroverted; in an ideational culture it is introverted. The former preaches the inner-directed values of humanism, the latter preaches the outer-directed values of materialism. Life view in a sensate culture stresses becoming; in an ideational culture it stresses being. The former thus preaches progress and modernity. The latter preaches the stability of tradition.

To bring such lofty sociological ideas closer to the world of empirical market research Zetterberg (1992, 1995) has fitted them into a three-dimensional value space (see Figure 3). The resulting system of value measurement and presentation was given the brand name Valuescope.

The first dimension, depicted from south to north, runs from being (e.g. being traditional), where one upholds stability, to becoming (e.g. becoming modern) where one welcomes change. Modernism initially took shape under a banner bearing the slogans "faith in reason" and "technology." The 20th century gave modernism a new content beyond rationalism: an élan vital, to use Bergson’s phrase. Nietzsche’s contribution was creative self-realisation, the idea of a sunny superman (Übermensch) who, unrestricted by traditions, creates himself and his world. Freud contributed therapeutic expression of drives, enabling the 20th-century human beings to affirm their biological selves, live for the moment and deny the magnitude and character-moulding features of suffering.

The second dimension, which runs from west to east, spans the field from value fidelity, where one dramatises one’s values, to instrumentality, where one compromises one's values. Value fidelity — which can be called idealism if you approve of the value or dogmatism if you disapprove of it — embraces values that one will not compromise. They typically include matters of conscience, such as loyalty toward one’s family, solidarity with the weak, compassion for the ill, saving planet earth for future generations. Instrumentality — that can be called pragmatism if your approve of it or opportunism if you disapprove — includes values that we can experiment and compromise with to obtain an optimal result; they typically include practical deliberations and calculations in business or politics and the selection of technical solutions. The distinction between value fidelity and instrumentality was most explicitly drawn by the German sociologist Max Weber in the early 1900s. Value rationality, wertrational actions, was separated from instrumental rationality, zweckrational actions (Weber 1956, pp 12-13).

The third dimension runs from the valleys to the mountains in the diagram. It separates a concern with material things from a concern with human beings, thus bridging the poles of materialism and humanism. Such labels have many connotations. Several other designations can be used, including Sorokin’s original terms sensate and ideational. Materialism may also stand for "values of production" such as order, punctuality, ambition, efficiency and other values promoting economic growth. Humanism may stand for "values of reproduction" such as self-development, empathy, sensitivity to and concern for others, and other qualities necessary for personal inner growth and a genuine understanding of other people. Arnold Mitchell (1983, chapter 2), as we have seen, refined and re-labelled the opposite poles of this dimension in his distinction between Outer-directed and Inner-directed. Values that appeal to external cues are called outer-directed or materialistic. Values that appeal to internal cues are inner-directed or humanistic.

Figure 3. Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft in a Three-Dimensional Value Space

For a hundred years, sociologists and others have had an understanding that society has moved from Gemeinschaft to Gesellschaft (Tönnies 1887). The three-dimensional view of values shows that this is not the only possible path. Gemeinschaft represents being stable and showing value fidelity and humanism. Gesellschaft represents becoming modern, pragmatism, and materialism. But a present-day society may embrace humanism rather than materialism — this is the message from the feminist movement. And it may embrace fidelity rather than pragmatism — this is one of the messages from the environmentalist movement. Such movements are actually part of the modernity of our times, not necessarily calls to return to tradition. But they represent a different way of becoming modern without the pragmatism of the industrial era or the spirit of compromise of the parliamentary era.

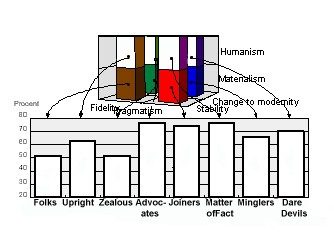

To obtain Valuescope’s classification of value carriers, the population is divided according to types depending on their high or low position on each of the three dimensions. We then get eight types of value carriers. In all value research it is wise to refrain from classifying those who have nearly equal scores on all dimensions. Methodologically they are uncertain to classify, and in real life they represent the minority who have average values on all dimensions. In Valuescope they form a ninth group called Centerites. The others are given the labels Folks, Uprights, Joiners, Matter-of-Fact, Zealots, Advocates, Minglers, and DareDevils. The table below summarises the division and gives thumbnail sketches how they might appear in Europe in the 1990s.

Value Carriers

| Uprights | Being traditional |

Fidelity |

Materialism |

| Old-fashioned people who mean it when they say "You must!" and "You must not!". The Upright are patriotic and often suspicious of strangers and immigrants. They hate inflation and love law and order. As consumers they are cautious and apprehensive about experimenting. They like tried and true products. | |||

| Folks | Being traditional |

Fidelity |

Humanism |

| The Folks are more concerned with family and relatives than with the material base of existence; old-fashioned religion thrives here. As with the Uprights, love of the home community and the preservation of its traditions and surrounding nature are important concerns. Service to the next of kin is self-evident. When buying they often follow the advice of their long-time local retailer. | |||

| Matter-of-Fact | Being traditional |

Instrumentality |

Materialism |

| In this segment one seeks practical and technical rather than traditional solutions. Do-it-yourself is common. Your car and residence, not only your family, signal who you are. As consumers The-matter-of-fact are more ambitious than the Uprights and the Folks. They are not trendy; often they go for big brands and standard products. | |||

| Belongers | Being traditional |

Instrumentality |

Humanism |

| These sociable but old-fashioned people believe that friends and clubs, not only family and possessions, signal your identity. In joint efforts they have learned to influence their conditions. As consumers they may like to bargain pleasantly in looking for value for money. | |||

| Advocates | Becoming modern |

Fidelity |

Materialism |

| Here are the people who like the comfort of modern living but do not use material goods as status symbols. They are convinced of the merits of their values and want to change society to correspond to their values, not to adjust themselves to society. They are pro-environment and anti-commercialism. They are fairly big consumers but they are usually suspicious of advertising. | |||

| Zealous | Becoming Modern |

Fidelity |

Humanism |

| Emotion and intuition and empathy are meaningful for the Zealous. Like the Advocates they question tradition, hierarchy, and authority. They embrace not only environmental and Third-world causes as the Advocates but are also stronger on issues such as peace, feminism, multi-culturalism, gay rights, and/or animal rights. They are very critical consumers who tend to look for personal experiences rather than material things in the market place. | |||

| DareDevils | Becoming Modern |

Instrumentality |

Materialism |

| Unafraid of the complexity of life they look for and enjoy challenge, e.g. entrepreneurship, risky lifestyles in sports and/or in financial markets. Their bonds to products, causes, and people may, however, be short-lived. They continually ask, "What works for me?" and are ready to discard anything that is no longer flashy or profitable or useful. They are very interested in the technical features of the hardware they buy, but volatile in their pursuit of fashion in clothing, of cars, and of interior design. | |||

| Minglers | Becoming Modern |

Instrumentality |

Humanism |

| Trendy networkers thriving on cosmopolitan contacts and markets. Eating an ethnic dish a day is a matter of course. Interest in new expressions of personal life is intense. In their way of living they often like to combine familiar fragments in unexpected ways as in a music video. The Minglers are sophisticated consumers, more interested in software than hardware. | |||

| Centerites | |||

| They have nearly mean scores of all value dimensions. Methodologically they are uncertain to classify. They represent the minority who have average values on all dimensions. | |||

These nine categories are proposed as valuegraphics in the Valuescope system in parallel to demographics of age, sex, occupation, etc. in interviews using questionnaires.

As an example, we calculate and chart possession of driver’s licences in West Germany in 1996. We find that among Uprights, Folks and Advocates there are significantly fewer car drivers. Knowing their values we understand that they abstain from driving cars for rather different reasons. The Uprights and Folks because they live with the traditional idea that only males do the driving, the Advocates because they want to live a modern, ecologically sound life relying more on public transportation.

Figure 4 shows the shares of car drivers in each segment and the location of the segment in value space. The numbers in the bar chart are percentages of the various value groups.

Ad hoc Systems of Value Measurements

We turn now to systems of value measurements that do not depend on a prior theory. Here we find the big international brands of commercial value research.

The oldest is The Yankelovich Monitor developed in the United States by Daniel Yankelovich. It has its origin in the late 1960s in the studies of the changing values on American campuses (Yankelovich 1972). In the 1970s Alan de Vulpian of Cofremca in France and others developed a system used in many countries for measuring values called RISC (Research in Sociocultural Change). RISC was incorporated in 1978 as an internationally operating research firm. Yankelovich and de Vulpian have since relinquished the corporate control of these international brands. de Vulpian together with the Italian pioneer of value research, professor Gianpaolo Fabris, market their versions of continual value research as 3SC.

The Yankelovich Monitor, the RISC system and 3SC all rely on fairy long questionnaires. The researchers do not start from a specific theory, they include any item that might catch the relevant values of contemporary times. Data reduction and analysis are performed by statistical techniques such as correspondence, cluster, or factor analyses. Pioneering methods have been invented for the tracing of the bifurcation of values. New items are added to their questionnaires from time to time to keep up with changes in the value climate. The ad hoc nature of these systems have made them non-dogmatic and always of interest for those who have to cope with marketing implications of the Zeitgeist.

Correspondence Analysis and the Study of Gravity Points

The well-known French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu has promoted methods of research that minimise the distortions of the researchers’ preconceived ideas. He has done so in many areas of social science, including research into taste and values. One advanced aspect of such method is the use of correspondence analysis. Correspondence analysis is a statistical technique that is more popular in France and Japan than in Anglo-Saxon countries. It renders a graphical representation of crosstabulations and establishes a purely empirical distance matrix.

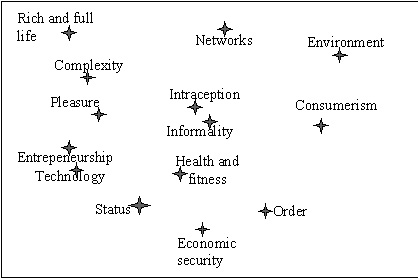

To glimpse the structure of the values of the times by means of interviewing without any preconceived idea one would have to start with a large sample of the respondents’ expressions representing their possible values. Every answer would be tabulated against all other answers. You quickly get lost in interpreting the latter undertaking. Instead one can plot answers to value questions by correspondence analysis. An example is found in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Correspondence Analysis of Selected Value Responses. Sweden 1982

The only measures that mean anything in a chart from a correspondence analysis are the distances between the points. They are the same whether the chart is tilted, turned upside down, or, converted by a mirror. The chart does not have fixed axis; they do not have to be horizontal and vertical, they can be drawn in any direction. (As an example, the left and right sides are switched in Figures 5, 6, 7 and 9 compared to all other diagrams in this section on ad hoc measurements of values.) The distance between the points would in all these instances nevertheless be the same. And the meaning of the distances is simple: they show difference. For example, the points of pro-entrepreneurship and pro-technology are close, and this means that these values often tend to reside in the same persons. The points of pro-technology and pro-environment are further from one another, and this means that these values tend to reside in different persons.

Note that the points in the correspondence charts represent centres of gravity. Individual readings for all the respondents would appear as a cloud around this gravity point. We tell how well the chart can represent the true distances by calculating a coefficient called "stress", indicating the amount of force used to fit the gravity points to the data. If the stress is high it might be necessary to include a third dimension in the correspondence analysis.

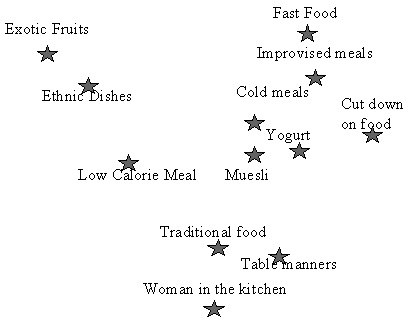

We may add other items than value responses to the correspondence analysis, e.g. products or services used by the respondents, the mass media they normally use, or the opinions or memberships they hold. Let the points representing the values fade into the background (or turn into small print) and what stands out is a map of the markets for products, services, media et cetera. For example, if the gravity points of two brands are close, they compete for attention among people with similar values; if the points are at a distance they appeal to people with mutually different values. Such information guides decisions about positioning and repositioning of products and services. Figure 6 is a simplified example from a Swedish food survey from 1982.

Figure 6. Food Preferences Imposed on the Value Map in Figure 5.

It is a common experience that executives very quickly grasp the meaning and content of these types of graphs, often called "maps". The relations on the map can also be expressed numerically in a table, just like the automobile atlas has a table of distances between the major cities.

Cluster Analysis and the Establishment of Target Groups

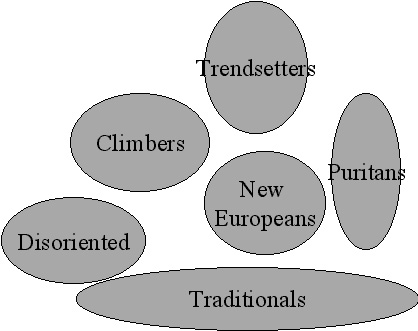

Utilising a so-called "cluster analysis with drift" we can continue an ad hoc analysis of values without any prior theory. The goal here is to put individuals with similar values into the same target group. Such non-hierarchical clustering of individuals was almost impossible prior to the advent of the computer and its iteration abilities.

The non-hierarchical cluster analysis in the computer is like a huge cocktail party. In the beginning the hostess arbitrarily puts people in, let us say, twenty or thirty different circles, so that they can talk to each other. They compare the values they subscribe to. The persons whose values deviate the most from the mean of the circle are sent away to another circle in the party. The process continues in numerous rounds until the differences in values between circles are maximised and the differences between individuals within circles are minimised. At the end, everyone at the party has found a circle with nearly the same values as himself or herself. Such circles, of course, can be of very unequal size. If too many groups are created you can relax the criteria of sameness or ask the smallest group to dissolve and merge with others so that the number becomes manageable: six to ten value groups might be enough for most marketing applications.

After its first all-European survey RISC found six clusters of Europeans entering the 1980s. See Figure 7.

Figure 7. Clustering the European Population

Factor Analysis and the Establishment of Axis and Sectors and Segments

With correspondence analysis and non-hierarchical cluster analysis we reveal the structure of the value climate without imposing any preconceived idea on the data. Most researchers prefer, however, to impose at least common co-ordinates on their data, and give names to the north, south, east, and west of their maps. By imposing common latitude and longitude on their maps, the early geographers could begin to relate the tales of different travellers to one another and make geography a cumulative science. The practitioners of ad hoc value research have felt the same need.

The statistical technique of factor analysis will find systems of co-ordinates and, by rotations, find optimal axis. When value researchers change, as many did around 1990, from correspondence analysis to a rotated factor analysis there was no great change in the resulting value maps. There is, however, an assumption that the axes do mean something in the real world.

A factor analysis will also reveal how many axis (factors) are required to fully represent the data. For many years RISC used a two-factor solution but in analysing the 1993 interviews RISC changed to three factors.

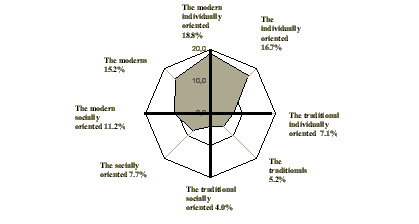

The researcher must upon inspection of how various interview questions have fared in a factor analysis invent appropriate names to the factors. In Denmark, for example, Flemming Hansen (1997) used a two-factor solution and called the dimensions Traditional vs Modern and Socially Oriented vs Individually Oriented. Without much violence to the same data another researcher could probably have chosen the RISC labels used, namely, Resistance to Change vs Openness to Change and Hedonism vs Ethics (Hasson & Ladet 1994, p 199). One must be careful in judging different models of value research and not assume that they are the same or different simply because the researchers have given their factors the same or different stickers.

Instead of a cluster analysis to find groups with different values, the user of factor analysis in value research has other options. He may use the sectors ("pie slices") of his system of co-ordinates to define groups with similar values. Or, he may convert the factor scores to percentiles and impose a grid on his data that delineates the value groups. The latter method produces the more homogenous groups. Examples of outcomes of these two methods are found in Figure 8 from Denmark (Hansen 1997) and in Figure 9 from Norway (Hellevik 1996, p 66).

Figure 8. Per Cent Coca-Cola Drinkers in Denmark in Value Groups Delineated by Sectors

Modern |

||||||

| 38 | 55 | 61 | 69 | 77 | ||

| 45 | 57 | 64 | 71 | 81 | ||

| Materialistic | 53 | 63 | 71 | 77 | 86 | Idealistic |

| 55 | 71 | 78 | 84 | 89 | ||

| 76 | 81 | 86 | 92 | 95 | ||

Traditional |

||||||

The research group Agorametri in Paris found that the quadrants (in a two-factor solution) have definite and dynamic meanings when they studied a full set of public controversies in France over several years (Durand, Pages, Brenot & Barny 1990). New public opinions originate in a quadrant where people celebrate change and love to dramatise their views, then spread to the quadrant where they celebrate change but compromise their views, and then to a quadrant where they celebrate stability but compromise their views. Finally, the opinions spread in the quadrant where people celebrate stability and dramatise their views. By then the critical intellectuals of the first quadrant have long since found new causes to promote.

Questionnaires in Value Research

The first point we want to make about questionnaires in value research is that they should not rule out demographic items. There are clear correlations between the demographic categories and the value groups. For example, the young generally support the change to modernity more than do the old. Men tend to be more materialistic than women.

We shall not join here the great debate between Hegelians who argue for the primacy of values and Marxists who argue for the primacy of social structure. In the data available, both are partially right, one more than the other depending on the concrete issue at hand. In every country we have studied there are correlations between demography and values but demographics and valuegraphics each contribute a unique piece of market information, small or large, to the concrete issue at hand. This is the reason why both questions about demography and values are needed in the questionnaires. Attempts to combine them into one and the same typology have, however, so far been less successful.

The questionnaires for the theory-based systems of value measurements are used only to calibrate but not to define the dimensions. In this approach the dimensions of value space are given in theoretical social science. In other words, the general attributes of values are anchored in theory and shall not be obtained pragmatically from the items by means of a factor analysis or similar method. Instead of listing the great variety of specific values that are found in the real world they should only reveal the few general attributes of values found in the theory. Hence the questionnaire used as measurement can be short. It shall normally relate directly to the definition of values, i.e. have face validity. If values are priorities how we want to live, then the questions used should present situations of choice in which some alternatives are chosen and others rejected.

If your theory has only one dimension, you may be satisfied with only one interview question. The pioneering measurement of materialism-postmaterialism (Inglehart 1970) required only one interview question. The respondents were asked their priorities in regard to four national goals: (a) maintaining law and order, (b) give people more of a say in national decisions, (c) fight rising prices, and (d) protect the freedom of speech. The respondents were asked to make a choice of two out of these four alternatives. Those who picked (a) and (c) were called "Materialists", and those who picked (b) and (d) were called "Post-materialists". All other combinations of choices were "Mixed". This will work so long we stick to definitions of materialism as concern for security and of postmaterialism as concern for democratic freedom. The single question, however, is too sparse to represent a full modern value space in which to place, say, class issues, feminist, ecological and libertarian politics (Cf. Hellevik 1993). But the use of the original materialism-postmaterialism measure nevertheless represents a scheme for asking about priorities that is entirely in accord with to our definition of values.

A general rule of questionnaire construction is that the questions should not be too bureaucratic or academic but relate to everyday life and ordinary speech habits. The response alternatives used in the materialism-postmaterialism measure come close to being academic but have actually worked well in over 20 countries. The choices used to calibrate the Valuescope dimensions are less abstract. They deal with situations such as choosing television programmes, preference of persons with whom to spend a weekend, and expressing three wishes to the good fairy. They have been tested in Anglo-Saxon, Latin, Germanic, Finno-Ugric, and Japanese languages and they calibrated the three theoretical dimensions adequately in all these languages.

The criteria for questionnaires for the ad hoc systems of value measurements are different. Here the questions used shall both define (e.g. by factor analysis) and calibrate the dimensions of the value space. This requires many more questions. Often they are listed as statements to which the respondents shall agree or disagree.

The Yankelovich, 3SC, and RISC value monitors also want to reveal from time to time what is new on the value front, including new and fading dimensions of the contemporary value space. Their customers want a better understanding of the values in the emerging business environment. To formulate interview questions for this purpose the researchers need contacts with the avant guard. As preparatory work for the construction of a value questionnaire they can use qualitative interviews with pioneering souls, they can listen to adolescents in bellwether cities and quarters, they can make content analyses of the new fads on the internet, et cetera. This type of research is clearly a task for the worldly and sophisticated.

Barker, David, Loek Halman & Astrid Vloet 1993. The European Values Study 1981-1990: Summary Report, Cook Foundation, London

Bourdieu, Pierre 1979. La distinction. Critique sociale du jugement. Minuite, Paris. English translation 1986, Distinction. A Social Critique of Taste, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London.

Douglas, Mary 1982. In the Active Voice, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London.

Gunter, Barry and Adrian Furnham 1992. Consumer Profiles: An Introduction to Psychographics, Routledge, London & New York.

Durand, Jacques, Jean-Pierre Pages, Jean Brenot, Marie-Hélène Barny, "Public Opinion and Conflicts: A Theory and System of Opinion Polls" International Journal of Public Opinion Research, vol 2, no1, 1990, pp. 30-52.

Edwards, A L 1954. Personal Preference Schedule: Manual, The Psychological Corporation, New York.

Hansen, Flemming, 1997. "From Life Style to Value Systems to Simplicity" to appear in Advances in Consumer Research 1997, Association for Consumer Research.

Hasson, Larry & Michel Ladet 1994. "New Cultural Maps for the 1990s: the Future Axes of Consumer Needs", 47th ESOMAR Marketing Research Congress, Amsterdam, pp. 197-207.

Hellevik, Ottar 1993. "Postmaterialism as a Dimension of Cultural Change", International Journal of Public Opinion Research, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 211-233.

¾ 1996. Nordmenn og det gode liv. Norsk Monitor 1985-1995, Universitetsforlaget, Oslo.

Hofstede, Geert 1980. Culture’s Consequences. International Differences in Work-Related Values, Sage, London.

Inglehart, Ronald 1971. "The Silent Revolution in Europe: Intergenerational Change in Post-Industrial Societies", American Political Science Review, vol. 65, pp. 991-1017.

¾ 1990. Culture Shift in Advanced Industrial Society, Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ.

Kluckhohn, Florence Rockwood and Fred L Stodtbeck 1961. Variations in Value Orientation, Row Peterson, Evanston, Ill.

McLuhan, Marshall 1962. The Gutenburg Galaxy, University of Toronto Press, Toronto.

Mitchell, Arnold 1979. Social Change: Implications of Trends in Values and Lifestyles, SRI, Menlo Park, (proprietary).

¾ 1983. The Nine American Lifestyles, Macmillan, New York

Morris, Charles 1942. Paths of Life. Preface to a World Religion, Harpers, New York.

Riesman, David, Nathan Glazer, and Reuel Denny 1953, The Lonely Crowd, Yale University Press, New Haven, Conn.

Rokeach, Milton 1968. Beliefs, Attitudes, and Values, Jossey-Bass, San Fransico.

Sampson, Peter 1992. "People are People the World over: the Case for Psychological Market Segmentation", Marketing and Research Today, vol. 20, no 4, pp. 236-244.

Sorokin, Pitirim A 1937-41. Social and Cultural Dynamics, (4 vols.), American Book Company, New York.

Schwartz, S.H. 1992. "Universals in the Content and Structure of Values. Theoretical Advances and Empirical Tests in 20 Countries, in Zanna, M. (ed) Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Academic Press, San Diego, pp. 1-65.

¾ & W. Bilsky 1987. "Toward a Universal Psychological Structure of Values", Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 53, pp. 550-562.

¾ & W. Bilsky 1990. "Toward a Theory of the Universal Content and Structure of Values", Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 58, pp. 878-891.

Tönnies, Ferdinand. 1887. Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft, Fues Verlag, Leipzig.

Weber, Max 1956. Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft, 1. Halbband, J.C.B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck), Tübingen.

Yankelovich, Daniel 1972. The Changing Values on Campus, Washington Square Press, New York.

¾ 1997. "How Societies Learn: Adapting the Welfare State to the Global Economy", published lecture May 14, City Universitetet, Stockholm.

Zetterberg, Hans L 1992. "The Sociology of Values: the Swedish Value Space", paper presented at the 87th Annual Meeting, of the American Sociological Association, August 20-24, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, reprinted in revised form in Richard Swedberg & Emil Uddhammar (eds) Sociological Endeavor , City University Press, Stockholm 1997, pp. 191-219.

¾ 1995. "Valuescope: A Three-Dimensional Value System", in Flemming Hansson (ed), European Advances in Consumer Research, vol. 2, Association for Consumer Research, Provo, Utah, pp. 163-171