|

INDIKATOR is the name of the political newsletter from Sifo (Swedish Institute for Opinion Research). This English-language issue is a service to the international press covering the 1982 Swedish Election. Sifo researchers Karin Busch and Hans L Zetterberg will also be available to the press at 10 am September 17 at the Press Centre of the New Parliament Building to comment on Sifo’s final pre-election poll released in the morning papers the same day. [Table of Contents at the end] |

We gratefully acknowledge a

grant from the Foreign Office to prepare this issue in English. Needless

to say, the Foreign Office or the Swedish government have no

responsibility whatsoever for the content of this issue; Sifo is a private

research house, undependent of party politics. We describe the political

situation and make our forecasts on the bases of data available to us,

irrespective of which party or interest group they may seem to benefit.

Our objective is not to try to be a friend to all or even to a few but to

be respected for honest, accurate work.

The researchers at Sifo who have worked on the election polling are Karin Busch and Hans L Zetterberg. In this release they have pooled their interpretations and drawn on previous issues of INDIKATOR and other published polls. |

The 1982 election deals with two fundamental issues of international interest: the shrinkage of the welfare state in an ailing economy and the gradual socialization of the private sector of the economy according to a new model, the wage-earner funds. The nation's non-socialists are accused of wanting to cut government spending by diminishing the welfare system that had provided post-war Swedes with cradle-to-grave-security. The Social Democrats are in turn accused of trying to socialize the economy through the introduction of wage-earner funds designed to gradually transfer stock ownership from private to public and/or union control.

The Social Democrats emerge the winner in most debates about welfare policy, the non-socialists win most debates about wage-earner funds. The electorate, however, balks at taking stand on such portentous issues: most people want neither cutbacks in welfare nor collective ownership of the means of production.

A majority may vote for the Social Democrats on September 19 as defenders of the welfare state, not as socializers of the economy. Whether the Social Democrats will use their mandate mainly to defend the welfare state in hard times, or also to introduce wage-earner funds is the real implication of the election. If they successfully do the latter, their model to socialize an advance economy may be copied in other countries.

In the middle part of the twentieth century two blocs have competed for the Swedish government. On the one side, we have the non-socialist bloc: the Moderates (before 1969 called Conservatives), the liberals, and the Centerites (before 1958 called Agrarians). On the other side, we have the Social Democrats and (since 1917) the Communists. The Communists have not entered the socialist governments. But the Social Democrats have been able to count on them not to vote a socialist cabinet out of office at the many times in recent decades when the Social Democrats have been by far the largest party but nevertheless not quite reached an absolute majority in Parliament.

The party structure has been amazingly stable throughout the entire twentieth century: world wars, depressions, and booms have come and gone but the parties have survived. A Swede who had turned into a Sleeping Beauty in 1920 and woke up in 1982 would not have any difficulty in recognizing the parties although all of them except the Social Democrats have changed their names.

There is, however, in the 1982 election a small crack in the otherwise so stable party structure. The strong environmentalist movement in Sweden has earlier had its political home mostly among the Centerites. However, in time for the 1982 election, an ecologist (green, or, alternative) party has been formed in Sweden. It is called the Environmental Party.

The code names of the parties used by all media and recognized by most Swedes are:

| c | Center Party (previously Agrarian Union) |

| fp | Liberal Party (literally People's Party) |

| kds | Christian Democratic Union |

| m | Moderate Party of Unity (the Conservative Party) |

| mp | Environmental Party |

| s | Social Democratic Workers' Party |

| vpk | Communist Party of the Left |

Looking at the balance between the socialists and the non-socialists, the four elections in the 1970s were all close, and the 1973 and 1976 elections were cliff-hangers where parliamentary distribution. of seats was not available on election night but required recounts.

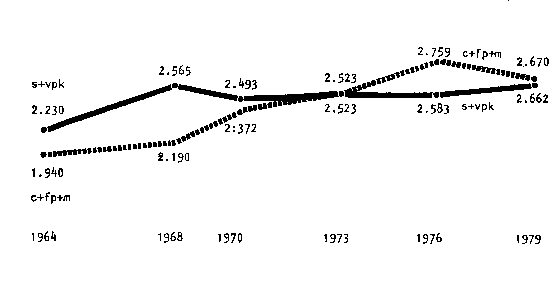

The bloc votes (in thousands) in recent elections are shown in this diagram:

The closeness is, of course, no law of nature and we anticipate a wider gap in this election (see also page 47).

Turnout has been high in recent elections:

| 1968 | 89.3% |

| 1970 | 88.3% |

| 1973 | 90.8% |

| 1976 | 91.8% |

| 1979 | 90.7% |

Swedes are allowed to cast their vote in the post office between August 20 and September 19 and do not have to go to the polling stations on Election Day, September 19. This, of course, makes it convenient to participate in the election. However, one should not take a high voting level for granted; the 1982 turnout may well fall short of the high-water mark set in 1976 (see also page 49).

There is one chamber with 349 seats in the Swedish parliament (riksdag). Of these 310 are so-called fixed seats (fasta mandat), the number varying from 2 to 29 per constituency (valkrets). The total number of constituencies is 28. The remaining 39 seats are adjustment seats (utjämningsmandat) which are distributed among the parties in order to give them a representation In the Riksdag absolutely equal to the proportion of votes in the whole electorate. These rules are applicable only to parties attaining 4 percent or more of the total number of votes cast in the whole country. A party that has not reached this share may nevertheless be represented in the Riksdag if the party has obtained 12 percent or more of the votes in any one constituency.

The 1982 polls put the Communists and the Environmentalists close to the 4 percent threshold, and considerable attention is focused on whether they will be in or out of the 1982 riksdag (see also pages 50-52).

If the Communists in the polls appear to fall below 4 percent some Social Democrats may consider lending them a helping hand. A Social Democrat this inclination is known in Sweden as "a Comrade-Four-Percent". voters believe that they trade the last seat of their own party to 14 seats (4%) of Communists to make the victory of the socialist bloc more certain. Pollsters play an uncomfortable role in this process since their figures normally lack the precision required to make such decisions.

Entitled to vote are all Swedish citizens aged 18 on the day of the election. Swedes residing abroad are permitted to vote on application if they been residents in Sweden some period of their life.

The elections to County Councils (landsting) and Municipal Councils (kommuner) take place on the same occasion as the elections to the Riksdag. Foreign nationals who have been registered Swedish residents since Nov 1, 1979 and are 18 on Polling Day are entitled to vote in the county municipal elections, but not in the parliamentary election.

The government weekly for immigrants, whose English language version is called News and Views, had a special election issue in August to inform non-nationals of their voting rights.

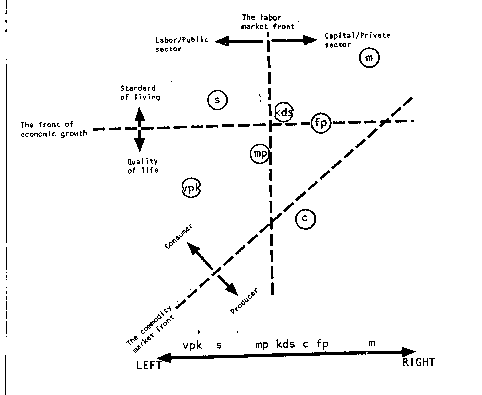

In the Swedish multi-party system, the parties' fight for votes is a war waged on all fronts. For a Liberal the struggle against the Conservatives can be as important as that against the Social Democrats. For a Social Democrat the battle against the Communists may seem as urgent as that a96inst the Center Party. There are, however, three main frontlines in the political battlefield of the 80s, and the parties may from time to time variously join forces along these lines. The three fronts are the labor market, the commodity market, and growth. The way the parties group themselves along these fronts is illustrated in our diagram:

Most clashes occur along the frontlines of the labor market. The struggle is for power over work and the workforce, the production apparatus, and its surplus profits. The frontline coincides with the preference for the private sector and the public sector. The forces are aligned as follows:

This frontline is the basis for the blocs in Swedish politics – the nonsocialists and the socialists, those who favor individual/entrepreneurial solutions and those who favor collective/egalitarian solutions.

The other front is the commodity market, primarily foodstuffs. The producers of foodstuffs are in conflict with consumers. At the heart of the conflict are the requisite conditions for primary industry and sparsely populated rural areas, subsidees to agriculture, and food-prices. The forces are aligned thusly:

The third frontline is growth. The fight is between supporters of growth and quality of life. It concerns the environment, large-scale 'uii-dustry, elaborate bureaucracy, heavy dependence on exports, decentralization. The forces are aligned thusly:

We recognize this front from the 1980 referendum on nuclear energy.

There are indications of other frontlines. One would be the front, where kds, the Christian Democratic Union stands alone against all other parties, with the possible exception of the Center Party. Yet another would be foreign affairs: APK, the Workers' Communist Party, is loyal to the Soviet Union through thick and thin, and stands in opposition to all other parties, while the Conservatives are viewed as more friendly to the United States than others. In contrast to many other countries, Swedish party structure does not evince any marked alignment along cultural-ethic lines.

The new Environmental party is quality-of-life oriented, is more nonsocialist than socialist, and differs from the Center party In that it is more concerned with the consumer than with the producer.

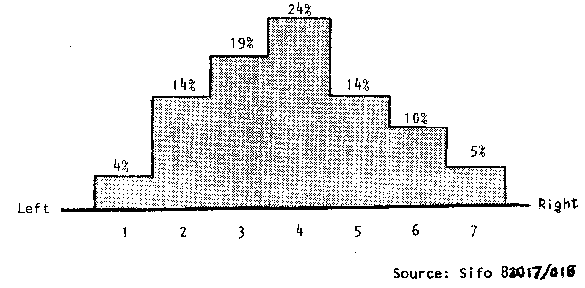

In April and May, 1982 Sifo asked voters to place themselves on a Right-Left scale according to seven rating points. The results are shown in the diagram below.

We note that the distribution is like that of a Gauss curve, but that it leans somewhat to the left. Swedish voters thus have a political profile that is slightly to the left. The average rating is 3.88. We find that 57 percent place themselves in the three middle positions (3, 4 and 5), that 18 percent view themselves as leftist-oriented (positions 1 and 2), and that 18 percent view themselves as right-oriented (positions 6 and 7).

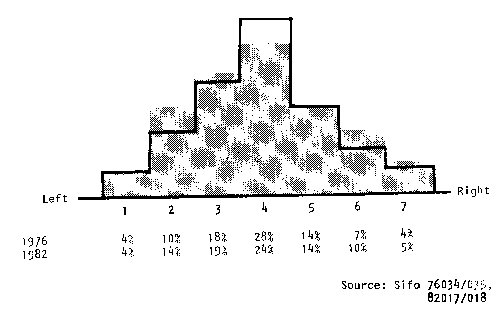

During the time the non-socialist government has been in power the distribution has moved toward greater polarization. The diagram below shows the distribution on the right-left scale in May and April of 1982 (the shaded area) compared with the distribution in August, 1976 (the solid line).

The averages did not change between 1976 and 1982, but we note that the distribution was slightly more concentrated around the middle of the scale in 1976 compared with 1982. The results this year show a greater polarization, with more voters who align themselves with both the left and right wings. The percentage supporting the left has increased from 14 to 18 percent, the percentage supporting the right from 11 to 15 percent.

Part 2 – CONFIDENCE IN THE SYSTEM

During the 705 we repeatedly ascertained that the publicls confidence in the Swedish model was dissipating. The growing distrust of politicians received the most attention in the media. This widening credibility gap hurt not only the politicians themselves but also political institutions, for example, Parliament and government agencies such as the Labor Market Board and the Board of Education. The corporative feature of Swedish society – the indisputable dominance of big business, big labor and big interest groups also met with increased skepticism. In the early 70's a decline in confidence was also the lot of the mixed economy, particularly the market economy. The widespread erosion in confidence among the general public in all these aspects of our system pointed toward a crisis of legitimacy, the kind of crisis that usually is a forerunner of change in systems.

By 1981 the situation had changed in a surprising way. The trend we have called "confidence in the system" has split into three components, each with a different development.

This diagram summarizes the course of development confidence in the system has taken:

Diminishing Confidence in Government

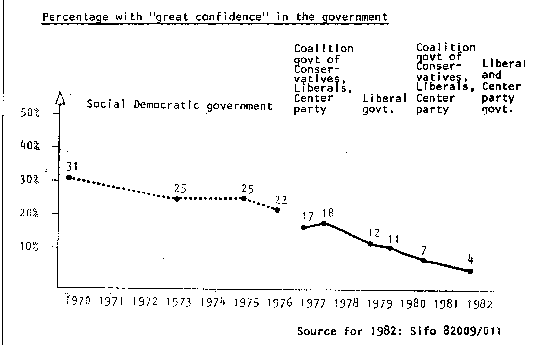

Confidence in the political system is still declining. Since 1970 Sifo has asked: "How much confidence do you have in the government – great confidence, neither great nor little, or little confidence?"

During this entire period confidence declined almost as rapidly under the socialist government in power prior to 1976 as under the subsequent nonsocialist governments.

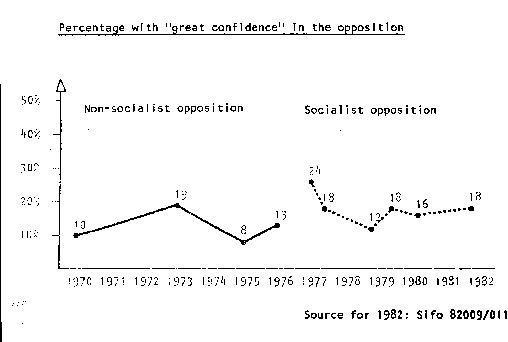

A corresponding question has been asked about the opposition: "How much confidence do you have in the non-socialist/socialist opposition – great confidence, neither great nor little, or little confidence?"

The declining confidence in the Government has not been balanced by an Increasing confidence in the opposition. Confidence has not moved from one group in society to another; it has disappeared from the palms of the politicians.

We illustrate the decline also with a question on the Parliament, wheel Sifo first asked during the period when socialists and non-socialists ht-jd the same number of members in Parliament (the number of MPs has since @5c-eh changed to an odd number: 349), the so-called "Lottery Parliament":

| 1974 | 1978 | 1981 | |

| Great confidence | 20% | 17% | 10% |

| Neither great nor little confidence | 39 | 43 | 41 |

| Little confidence | 30 | 33 | 45 |

| Don't know, no answer | 10 | 7 | 3 |

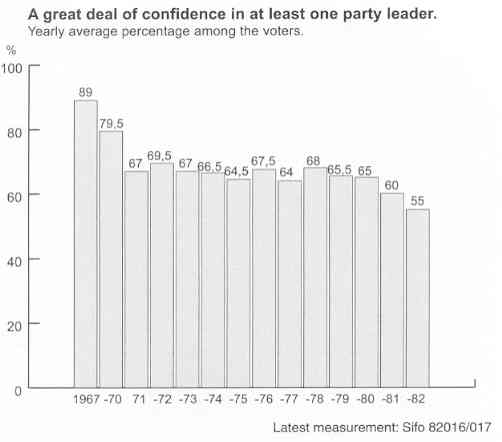

The percentage of people who have "a great deal of confidence" in at least one of the party leaders has fallen from 89 percent in 1969 to 55 percent In 1982.

The same trend is found in the following question, which is an everyday expression for political alienation: "Ordinary people get less to say in politics, do you agree or disagree?"

| 1978 | 1981 | |

| Disagree completely | 3% | 4% |

| Disagree somewhat | 11 | 6, |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 22 | 17 |

| Agree somewhat | 44 | 46 |

| Agree completely | 20 | 27 |

The same falling trend is found for government agencies. We have the following index figures for the School Board (SÖ) and the Labor Market Board (AMS):

| 1972 | 1978 | 1981 | |

| School Board (SÖ) | 3.46 | 3.19 | 3.10 |

| Labor Market Board (AMS) | 3.71 | 3.44 | 3.25 |

It should be noted that the Monarchy has not suffered from the general decline in confidence in political institutions.

Confidence in the Big Apparatus Outside of Government

The confidence in the large interest organisations – the corporate system has broken the do wnward trend. Since 1972 Sifo has asked:

"Large organisations such as the Co-operatiori, the Federation of Employers, and the Labour Unions as well as the large government agencies constitute iniportar it parts of our society. I'@icy take active part in the general debate on social questions, they inform in many ways on their activities and they express their views on societal is5ues.

What they say can have more or less credibility. 1 would like you to show me what degree of credibility you find in each of the following. SHOW CARD. Please use this card and the numbers from 1 to 6.1 means very little credibility and 6 means a great deal of credibility.

|

- - - LO - - - |

- - - SAF - - - |

TCO | |||||

| 1972 | 1978 | 1981 | 1972 | 1978 | 1981 | 1981 | |

| 1 Little credibility | 3% | 8% | 6% | 4% | 14.% | 13% | 7% |

| 2 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 6 | 12 | 14 | 12 |

| 3 | 16 | 21 | 21 | 15 | 23 | 24 | 29 |

| 4 | 21 | 24 | 25 | 17 | 22 | 24 | 27 |

| 5 | 15 | 14 | 18 | 12 | 10 | 11 | 10 |

| 6 A great deal of credibility |

17 | 13 | 14 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 3 |

| Index (average points) | 4.11 | 3.72 | 3.86 | 3.72 | 3.15 | 3.23 | 3.34 |

| Don't know, no answer | 20% | 10% | 6% | 40% | 16% | 9% | 12% |

(In the category "don't know, no answer" are registered both the persons who do not know these organisations and the persons without view on their credibility.)

The indices for the cooperative movement and the Federation of Swedish Industries also break the falling trend and increase. Averages on the six point scale are -

| 1972 | 1978 | 1981 | |

| Federation of Swedish Industries | 4.07 | 3.31 | 3.40 |

| The Co-operative Movement | 3.79 | 3.46 | 3.67 |

A recent international survey investigated, among other questions, the amount of confidence enhoyed by trade unions. It revealed that in Sweden and Denmark (the only Scandinaviari countries in the survey) the trade union movement enjoys more confidence than in other parts of Europe.

"How much confidence do you have in the trade unions? Do you have a great deal, quite a lot,, not very much or no confidence at all?"

Sweden |

Ten European Countries |

|

| A great deal of confidence | 8% | 5% |

| Quite a lot of confidence | 39 | 27 |

| Not very much confidence | 38 | 43 |

| No confidence at all | 16 | 21 |

| Don't know | 0 | 3 |

IF we rate "a great deal of confidence" as 4 points, "quite a lot. of confidence" as 3 points, "not very much confidence" as 2 points, and "no confidence at all as 1 point Swedish unions average 2.41 points.

| Average | Percentage who answered "no confidence at all" |

|

| Sweden | 2.41 | 16% |

| Denmark | 2.51 | 11% |

| The Netherlands | 2.32 | 12% |

| West Germany | 2.26 | 16% |

| Great Britain | 2.09 | 22% |

| Italy | 2.00 | 32% |

| Spain | 2.18 | 20% |

| France | 2.22 | 20% |

Confidence in the Market Economy

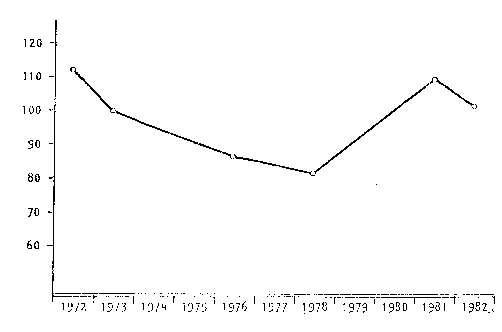

The Sifo index about the confidence in the market economy has returned to the high level it had at the beginning of the 1970s.

For ten years Sifo has carried on the following discussion with the public:

| 1972 | 1973 | 1976 | 1978 | 1981a | 1982 | |

| Good | 47% | 40% | 41% | 38% | 40% | 36% |

| Bad | 11 | 7 | 8 | 12 | 14 | 16 |

| Neither good nor bad | 8 | 11 | 9 | 13 | 11 | 9 |

| Uncertain, don't know | 34 | 42 | 42 | 37 | 35 | 39 |

"Sometimes we talk about 'state control'. Do you have the impression that it is good for the development of the society or that it is bad for this development?"

| 1972 | 1973 | 1976 | 1978 | 1981a | 1982 | |

| Good | 33% | 26% | 33% | 27% | 19% | 23% |

| Bad | 41 | 39 | 30 | 32 | 47 | 41 |

| Neither good nor bad | 12 | 13 | 11 | 18 | 16 | 15 |

| Uncertain, don't know | 14 | 11 | 26 | 23 | 18 | 20 |

| 1972 | 1973 | 1976 | 1978 | 1981a | 1982 | |

| …more on the market forces than now?" | 24% | 21% | 16% | 12% | 23% | 25% |

| …more on state control than now?" | 9 | 7 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 7 |

| …on the same mixture of the market forces and state control as we have now?" | 50 | 49 | 55 | 56 | 53 | 49 |

| Uncertain, don't know | 17 | 23 | 23 | 24 | 17 | 18 |

| Confidence in the market economy: | ||||||

| Index (total of the underlined figures in the three tables above) | 112 | 100 | 87 | 82 | 110 | 102 |

The underlined figures add to the index of confidence in the market economy shown in the chart at the beginning of this section.

A question on the entrepreneurial spirit may round off this review of the confidence in the market economy.

The Swedish public was asked this question in 1963, 1978, and again in 1982 by Sifo. During these nineteen years the entrepreneurship has lost much of its attraction, but is lately gaining appreciation:

| 1963 | 1978 | 1982 | |

| Start own business | 43% | 27% | 35% |

| Employee | 46 | 59 | 60 |

| It does not matter | 6 | 8 | 3 |

| Don't know, cannot tell | 5 | 7 | 3 |

When the historians of the future write about Palmels (first?) government they will probably stress the general decline of entrepreneurship along with many other more deliberate policy shifts. The upswing noted in the beginning of the 80's is strongest among the young.

What is Interesting to the Voters?

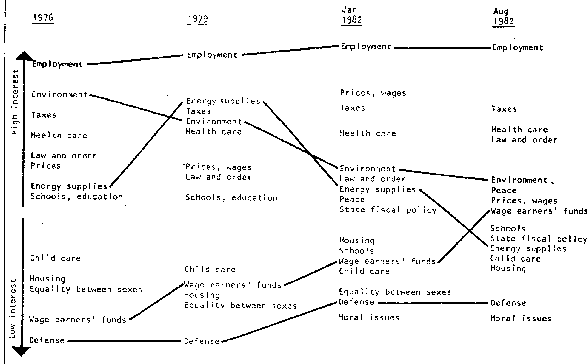

The voters' menu in regard to the issues that interest them has changed quite a lot during recent campaigns, but the primary issue remains the same – employment. In order to gain a perspective on this year's answers to the question "Which political issue is of most interest to you?" we shall compare them with the answers given in the two previous campaigns. The following diagram gives a schematic representation of how voters' interests have fluctuated.

Two new questions appear on the voters' list in 1982. One is the peace issue (a nuclear-free zone and disarmament) and the other is the issue of the state's fiscal situation (foreign debts, economy measures, the budget deficit). A number of questions related to the welfare system that came into the spotlight in conjunction with the government's economy drive represent new ingredients in the 1982 campaign. One, out of five voters has said that he is interested in welfare-related issues such as unpaid sick leave and pension guarantees.

Despite the intensity in the accusations "You intend to socialize!" and "You intend to slash welfare programs!" the electorate is unusually uncertain about what the conflict is all about in this election campaign. In addition it is not sure how the economic picture really looks.

Non-socialists and Social Democrats have long,been divided on acceptable levels for government spending and taxation. This schism seems to have deepened: non-socialists consider the government to be in far more severe financial constraints than do the Social Democrats.

LO's May 1 poster this year is a good indication of the Social Democratic view of economic rality: "Say no to unpaid sick-days! Sweden can afford social security." Compared with non-socialists Social Democratic politicians have more residues of the thinking habits prevalent during the period of almost continuous economic growth that coincided with Social Democratic rule after the Depression of the 19305.

In 1976 non-socialist leaders in government began by being even more magnanimous than Social Democrats in their budget for social expenditures, but during recent years they have grown increasingly restrained and do not believe it possible to increase taxes and government spending as before.

What are the voters to believe when one side asserts "We can afford it" and the other contends "We can't afford it"? There are today no economic experts who are above party politics and can give a credible answer. Even the OECD report on the Swedish economy is accused of political bias.

For several decades the idea that Social Democrats are good at welfare programs and employment and non-socialists are good at handling money and the economy has been widespread among voters. When the non-socialists won power in 1976 they were most eager to show that they, too, were proficient in handling welfare programs and the employement question. The Fälldin Governement's budget for social expenditures grew, and capital was poured into unprofitable enterprises in an effort to stem unemployment. As investments to win the good-will of voters these endeavors failed: they did notconvince more voters that non-socialists represented the welfare state and high employment. The Social Democrats have easily held onto their position as the safekeepers of the welfare state and high employment. This is of importance in elections that coincide with periods of unemployment, as in 1982.

What has happened during the non-socialist rule is an undermining of the government's fiscal state – and of confidence.in non-socialist politicians as capable financial managers. This change took place while the popular Gösta Bohman was minister of finance. Having lost much of their own ground and without having captured any of their opponent's territory, the nonsocialists face the electorate in 1982.

The Government's Fiscal Situation

The public has the greatest amount of confidence in the Social Democrats when it comes to managing State finances. Sifo asked "Which party do you think does the best job of managing State finances – the Conservatives, the Liberals, the Centerists, or the Social Democrats?" The Social Democrats got a confidence vote of 37 percent, and the three non-socialist parties together a vote of 31 percent. There is, however, a great deal of uncertainty, and one out of three voters answers either that there is no difference between the parties or that he does not know.

| Conservatives | 27% |

| Liberals | 2 |

| Centerists | 2 |

| Social Democrats | 37 |

| No difference | 15 |

| Uncertain, don't know | 17 |

The present non-socialist coalition government gets a very low vote of confidence on this issue. Only 4 percent answered "the Liberals" (2%) or the Center party (2%).

Employment Is Best Ensured By The Social Democrats

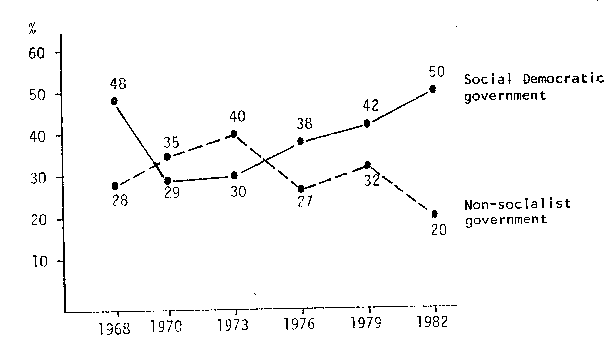

The Social Democrats enjoy a large and growing amount of confidence on the issue of employment. Half of all Swedes believe that a Social Democratic government would be most capable of ensuring employment in the nation. Ever since 1968 Sifo has asked this question a few months prior to each election day: "Which government do you think would be best able to ensure employment in the nation – a Social Democratic or a non-socialist one?" The answers are shown in the diagram below.

In the early 1970s the non-socialists enjoyed more confidence in respect to this issue than the Social Democrats, but since the election campaign of . 976 the situation has been reversed. Faith in the Social Democrats as Guarantors of employment grew during the '70s, and now 50 percent of Sweden's voters place their trust in 'the Social Democrats in regard to this issue while only 20 percent view the non-socialists as a mainstay of employment.

Whichever party or parties that form a government after the elections will have to deal with the question of the government's budget deficits. Eight out of every ten voters think the government should deal with this question in the first place through economizing, secondly by raising taxes, and thirdly by borrowing more money abroad. Sifo asked:

"What do you think the government should do after the elections in order to deal with our budget deficit – do you think it ought to raise taxes, introduce economy measures, or borrow more money abroad? What should we do in the first place, in the second place, and in the third place?"

| In 1st place | In 2nd place | In 3rd place | |

| Raise taxes | 14% | 62% | 9% |

| Economy measures | 81 | 14 | 2 |

| Borrow more abroad | 1 | 10 | 69 |

| Uncertain, don't know | 3 | 14 | 20 |

A majority among both socialists and non-socialists think that the government should first of all economize. Restraint in government spending is given more emphasis by Conservatives, liberals, and Centerists than by the opposing bloc: 93 percent among non-socialists and 70 percent among socialists give priority to economizing. Both socialists (71%) and non-socialists (67%) assign borrowing abroad third place among the alternatives presented.

One of the big political issues in this election campaign is the taxation agreement reached in 1981 by the Center party, the Liberals, and the Social Democrats. Their scheme is not primarily designed to increase taxes but to reshuffle them and limit the interest deductions for high-income earners.

Every other voter (52%) answers that he does not know whether the taxation proposal is a good or bad idea. Sifo asked:

"Do you think the taxation proposal put forth by the Social Democrats, the Liberal party, and the Center party is good or bad?"

| Good | 26% |

| Bad | 22 |

| Uncertain, don't know | 52 |

Few members of the parties that sponsored the proposal think it is bad (14% among Liberals, 16% among Centerists, and 13 % among Social Democrats). About one third answer that it is a good proposal (29% among Liberals, 34% among Centerists, and 30% among Social Democrats). The rest answer "don't know".

As may be expected, the Conservatives are more critical of the proposal: they withdrew from the government in 1981 because of their opposition to the taxation proposal and the way it was reached. Among the Communists those who consider the proposal bad also outnumber those who think it is good. They want to raise government revenue by a sales tax on the stock market trade.

| Good | Bad | Uncertain, don't know |

||

| Conservatives | 16 | 45 | 39 | 100% |

| Liberals | 29 | 14 | 57 | 100% |

| Centerists | 34 | 16 | 50 | 100% |

| Social Democrats | 30 | 13 | 57 | 100% |

| Leftist Communists | 19 | 32 | 49 | 100% |

After 100 years of political activity in Sweden the Social Democrats have put forth their first concrete proposal, based on a decision reached at a party congress, to break up private dominance in business. Health care, social service, communications, education, and much housing is already publicly controlled and owned. Now it is the business world's turn.

The non-socialist government has socialized crisis industries: steel, shipbuilding, and forestry. It has de facto socialized a greater number of industries in six years, 1976-1982, than the Social Democrats did during their 44-year reign, 1932-1976.

Now Social Democrats do not propose emergency aid to crisis industries but rather increased collective ownership of the viable parts of business life. LO took the initiative in regard to wage-earners' funds. After repeated revisions of LO's proposal by the Social Democrats, its intent has shifted from a form of guild socialism, whereby trade unions would be responsible for steering business concerns, to a democratic state socialism, whereby publicly elected officials would control the investments and the boards in business concerns. Both variations, the guild socialist and the more conventional socialist one, share a common feature in their Swedish version: the stock market, the heart of capitalism, is assigned a central role. The transition to collective ownership is to be achieved through open purchases on the Stockholm exchange or through direct offers to companies not listed on the exchange. There would be no overnight compulsory socialization as in Mitterrand's France. Nor would there be a central agency for state-held shares as in France, but rather several regionally based funds.

A considerable degree of uncertainty prevails among both Social Democrats and opponents to the funds about how much guild socialism and how much conventional socialism the funds entail. It appears clear, however, that local unions will get up to 20 percent of the votes at shareholders] meetings but no dividends which will, in the main, be deposited in the General Pension fund. There is an unresolved conflict between LO, which wants union representatives to be guaranteed a place on the governing boards of the funds and the position of the party leader, Olof Palme, who wants general elections to special legislative bodies that would in turn appoint boards for the collectively owned companies. General elections of the Western type would result in governing boards with a non-socialist majority in much Southern and central Sweden, where the business community flourishes. Elections of the Eastern European type – general elections, but only among candidates nominated by the powers that be – have not been discussed.

The proposals for the introduction of wage-earners' funds have given rise to a vehement and well-organized opposition in the business community. Its largescale campaign against the funds has focused more on the guild socialist aspects than on the funds' state socialist features.

Here follows some illustrations how these issues look in the polls.

Wage-Earners' Funds and The Control of Capital

Control of the investments and long-term planning of business is the core of the wage-earners' funds issue. Sifo was commissioned by the dailies Arbetet and Svenska Dagbladet to chart voters' opinions on this issue.

Sifo's interviewers asked 1,006 persons these questions.

We may summarize our results in percentages of all those interviewed:

As the campaign continues public opinion has grown increasingly adverse to the proposal for wage-earners' funds put forth by LO and SAP. Three out or four voters (73%) have by now taken a stand on this issue. Among the voters 57 percent are against the funds, 15 percent are for the funds, and 27 percent have not yet made up their minds. The gap between supporters of and opponents to the funds is 42 percent, 5 percent more than just before Midsummer. On the first leg of the campaign in Almedalen on the island of Gotland, Palme made a statement that he personally favored general elections to the governing boards of the funds. This public declaration hardly helped stem the drainage of support from the funds. Sifo posed this question:

Among Social Democratic supporters we find that 25 percent are anti-funds and 31 percent pro-funds. Within LO, 38 percent of the membership is anti-funds and 21 percent pro-funds. The remainder answer "don't know". These results did not correspond to our expectation that party loyalty would assert itself more noticeably as the campaign grew hotter. We do not find that increasing numbers of Social Democrats are closing ranks behind the funds.

The paradox we encounter in this campaign is that while a growing number of people are becoming negative to the funds, the Social Democrats still retain their advantage in our polls. A clear majority of voters are certain about their "no thanks" response to the funds, but the Social Democrats in the electorate are still pondering whether they will allow the issue to affect their vote on September 19th.

In August, pursuant to Palme's publicly stated personal view favoring general elections to the governing boards of the funds, Sifo asked voters these questions:

| "Are you of the impression that the Social Democrats and LO have the same view or different views on wage-earners' funds?" | All voters |

Social Democrats |

LO members |

|

The same |

34% | 32% | 38% |

|

Different |

38 | 34 | 28 |

|

Don't know |

29 | 33 | 34 |

| "LO wants funds in which the unions have the decisive say and Palme wants funds in which politicians have the decisive say. Whose opinion do you think will prevail, Palme's or LO's?" | |||

|

Palme's |

41% | 48% | 37% |

|

LO's |

32 | 23 | 30 |

|

Don't know |

27 | 29 | 33 |

| "If you had to choose, which would you prefer: funds that are controlled by the unions or funds that are controlled by politicians?" | |||

|

Unions |

23% | 30% | 32% |

|

Politicians |

48 | 40 | 34 |

|

Don't know |

28 | 30 | 34 |

It looks as if LO will be the loser in the struggle over control of the funds. LO's original intentions may be realized only by negotiaging directly with employers and by making the fund issue subject to contractual agreements. But the employers will not comply with this.

If Palme wins the election he will in no way be a captive of LO in respect to wage-earners' funds. He will be as independent of LO as Erlander was at the height of his power as Prime minister. Corporativism takes a step backward and political democracy regains a bit of ground in Sweden.

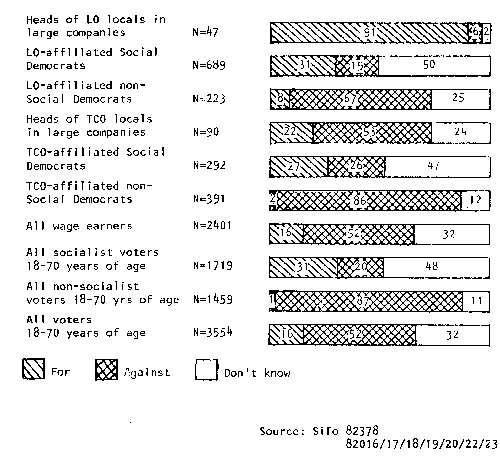

The diagram below shows the acceptance of the LO/SAP proposal on wage-earners' funds within different groups during the second quarter of 1982. The results are based on the question: "Are you for or against wage-earners' funds set up in accordance with the design proposed by the Social Democrats and LO?" The different areas within the bars represent percentages.

Swedes are growing increasingly skeptical toward state aid to ailing industries. They believe the government has invested too much in them and granted terms that are too generous.

| "The Government has had the state take over some companies in crises and has given other subsidies or loans in order to maintain employment. Do you think the Government has invested too much, too little, or neither too much nor too little in support of companies in crises?" | 1978 | 1982 |

| Too much | 21% | 45% |

| Too little | 23 | 17 |

| Neither too much nor too little | 36 | 20 |

| Uncertain, don't know | 21 | 18 |

| "Do you think Government support of companies in crises has been on terms that are too generous, too hard, or neither too generous nor too hard?" | 1978 | 1982 |

| Too generous | 34% | 49% |

| Too hard | 3 | 5 |

| Neither too generous nor too hard | 28 | 18 |

| Uncertain, don't know | 36 | 28 |

The issue of aid to ailing industry is highly associated with the name of Nils G Åsling, centerite minister for industry.

Non-socialists allege that they definitely want to maintain the welfare system; the Center party and the Liberals are especially inclined to protest when cutbacks are mentioned. The non-socialist majority in parliament has attempted to economize by reintroducing into the national health insurance, the qualification that the first two days of absence from work due to illness would no longer be reimbursed by the insurance plan, the so-called qualifying days. Non-socialists insist, however, that further savings in the state budget must be made. Automatic hikes in expenditures will total some 25 billion crowns next budget year, while the expected increase in tax revenues totals only about half that sum. Sweden is borrowing to the hilt from foreign banks.

The unions were incensed at the change in sick benefits put forth by the non-socialists, and wrote a common, threatening letter to the government. Stig Malm, the coming man in the National Federation of Trade Unions, warned of a political general strike. Social Democratic campaign propaganda contends the continued economizing is the non-socialists term for continued cutbacks in the welfare system. The Social Democrats spread posters proclaiming their defense of child allowances,.pensions and other benefits.

In regard to the most urgent issue for the voters, that of unemployment, the government defends its record by pointing out that it has taken more measures to counter unemployment than any previous Swedish government and that the result is a lower level of unemployment than in other nations: 166,000 unemployed or 3.7 percent compared to 10 percent in the OECD. But the Social Democrats promise to borrow and raise taxes in order to create more jobs through government spending.

Here follows a review how these issues look in the polls.

A majority within all the non-socialist parties are of the opinion that the proposal to introduce two initial unpaid days of sick leave (karensdagar) vas right. Most socialists oppose the proposal. Sifo asked: "Do you think it is right or wrong to introduce into the health insurance plan two initial qualifying days of sick leave that are not reimbursed by the health insurance offices?" The answers were as follows:

| Right | 35% |

| Wrong | 59 |

| Uncertain, don't know | 6 |

The question clearly divides the political blocs:

| Right | Wrong | Uncertain don't know, | ||

| Conservatives | 65 | 26 | 9 | 100% |

| Liberals | 63 | 31 | 5 | 100% |

| Centerists | 61 | 33 | 6 | 100% |

| Social Democrats | 14 | 81 | 4 | 100% |

| Leftist Communists | 2 | 94 | 4 | 100% |

Political strikes to protest against unpaid sick leave

One out of three adults (37%) believes that a political strike would be an appropriate means cf demonstrating against the new government measures, such as the introduction cf two qualifying days without reimbursement at the commencement of a period of absence from work due to illness.

One out of six Swedes (17%) says that he would be willing to participate in such a strike. Sifo asked:

"Do you think political strikes are an appropriate or an inappropriate means of demonstrating against government decisions, such as unpaid sick leave?"

| Appropriate | 37% |

| Inappropriate | 53 |

| Uncertain, don't know | 10 |

"Would you consider personally participating in a short political strike to demonstrate against unpaid sick leave?"

| Yes, willingly | 17% |

| Yes, maybe | 17 |

| No | 62 |

| Uncertain, don't know | 4 |

A majority within all the non-socialist parties consider political strikes inappropriate, and only a few individuals with non-socialist sympathies would consider participating in such strikes. Half of the Social Democrats, on the other hand, consider such strikes appropriate, and one out of three (30%) Social Democrats would consider participating in such a strike.

It should be emphasized that Sweden, unlike for example Great Britain, has no tradition of political strikes.

One of the issues that divides the political blocs in this election campaign is the disposition of child care benefits. Sifo asked:

"Which do you think is best – that the money politicians spend on child care for pre-school children be invested primarily in daycare centers or in child care allowances for parents?"

| All | Non-socialists | Socialists | |

| Day-care centers | 28% | 15% | 4o% |

| Child care allowances | 62 | 75 | 51 |

| Uncertain, don't know | 9 | 9 | 9 |

The Center party and the Christian Democratic Union are the most vigorous supporters of care allowances.

In the group most affected – families with preschool children – 59 percent opted for child care allowances and 34 percent for day-care centers. The women in this group are slightly more interested in daycare centers than in parents' allowances.

Parents of preschool children:

| All | Men | Women | |

| Day-care centers | 34% | 30% | 38% |

| Child-care allowances | 59 | 63 | 54 |

| Uncertain, don't know | 7 | 7 | 7 |

The Social Democrats often criticize the government for being too slow in building day-care centers. The near-stand-still of new construction is due to financial restraints.

If the Social Democrats win a majority on their own in September – as in the 1968 election and Sifo's latest political barometer – the government will naturally be Social Democratic. In this situation, a coalition government would be conceivable only in the event of a major foreign crisis.

If the election results are similar to those in 1970 and the Social Democrats emerge larger than the non-socialist parties taken together but without a majority of their own because of the Communists' (and now perhaps also the Environmental party's) mandate, the question of forming a government will be less clear. In February and March this year Sifo asked voters to address themselves to such an eventuality.

"Suppose the elections this autumn result in a socialist majority but the Social Democrats do not gain a majority by themselves, which kind of government would you prefer in such a situation?"

The 709 Social Democrats who were interviewed answered:

| A Social Democratic government that is sometimes supported by the Leftist Communists, sometimes by one of the non-socialist parties | 49% |

| A Government formed by the Social Democrats and the Center party | 15 |

| A government formed by the Social Democrats and the Liberal party | 19 |

| A government formed by the Social Democrats, the Center party, and the Liberal party | 10 |

| Uncertain, don't know | 7 |

A majority of Social Democrats (49%) would in such an eventuality want a Social Democratic minority government. This is the kind of government we have had so often in the past when election results have followed the pattern just described. The Leftist Communists who would have to support the Social Democrats in such a situation in all parliamentary questions that followed bloc lines, would back such a government up to 90 percent. A majority of non-socialists (78%) would prefer a coalition government to a Social Democratic minority government, but their opinion would hardly carry much weight of election results followed the pattern described.

If the non-socialists win the election – which only 25 percent of the voters now believe will happen – there are two possible outcomes: the Center party and Liberal party will together be larqer than the Conservative Party or vice versa. Sifo asked:

"Suppose therewill be a non-socialist majority as in recent elections and that the Liberal and Center parties together are larger than the Conservative party – which kind of government would you prefer in such a situation?"

The 645 non-socialists who were interviewed answered:

|

All non-socialists |

Conservatives |

Liberals |

Center party |

|

| A government formed by the Conservative party, the Liberal party, and the Center party | 59% | 76% | 30% | 38% |

| A government formed by the Liberal party and the Center party, which is sometimes supported by Conservatives, sometimes by Social Democrats | 18 | 10 | 30 | 29 |

| A government formed by the Liberal party and the Social Democrats | 9 | 4 | 35 | 0 |

| A government formed by the Center party and the Social Democrats | 9 | 5 | 3 | 24 |

| Uncertain, don't know | 5 | 5 | 2 | 9 |

We see that one out of five non-socialist voters (18%) and nearly one out of three Liberals or Centerists (29%) favors continued government by the Liberals and Centerists jointly. Those who favor the re-establishment of a three~party government total 76 percent among Conservative voters, 38 percent among adherents of the Center party, and 30 percent among adherents of the Liberal party. A minority of Liberals and Centerists (35% and 24% reso) want a coalition with the Social Democrats if election results followed this pattern.

If the non-socialists win the election and the Conservatives emerge not only as the largest non-socialist party but larger than the Liberal and Center parties combined, we will be confronted by a situation like that which followed the Norwegian elections in 1981. Sifo asked:

| All non-socialists | Conservatives | Liberals | Center party | |

| A government formed by the Conservative party, the Liberal party, and the Center party | 56% | 62% | 41% | 51% |

| A Conservative government that sometimes is supported by Liberals and Centerists, sometimes by Social Democrats | 24 | 29 | 17 | 15 |

| A government formed by the Center party and the Social Democrats | 7 | 2 | 4 | 23 |

| A government formed by the Liberal party and the Social Democrats | 7 | 2 | 31 | 3 |

| Uncertain, don't know | 6 | 5 | 8 | 8 |

The Norwegian solution with a Conservative minority government is favored by one out of four non-socialists (24%). A majority of adherents of all three non-socialist parties would in this situation favor re-establishment of a three-party government (62% among Conservatives, 41% among Liberals, and 51% among Centerists).

How do the voters react when they are asked to take a stand on portentous issues such as socialization of the economy and slashes in welfare programs when these questions are but vaguely defined for them and they are unsure what economic reality in fact amounts to?

One way of reacting is to rely on one's own experience and ask the old respectable question: "Has the government now in power handled itself so well that it deserves renewed confidence?" Experience indicates that answers to this question are gloomy for, governments that are in power during hard times.

The non-socialist Governments that were in power 1976-1979 were rated higher by the voters than the non-socialist Governments of 1979-1982. We have used this method of scoring:

| Very good | 5 points |

| Fairly good | 3 points |

| Poor | 1 point |

The average score given for the electoral period 1976-79 obtained through interviews made three years ago is higher than the average score for 1979-82. The first non-socialist electoral period received an average of 2.32 points, the second 2.12 points. The Government was rated in 16 areas in 1979 and in 17 areas in 1982.

Non-socialist voters gave the Government higher scores in the latter electoral period for its energy policies, taxation reforms, and the individual is increased determination over his housing. In other areas the 1982 scores are usually lower than the 1979 ones.

|

Non-socialists |

All voters |

|||

| 1979 | 1982 | 1979 | 1982 | |

| Economical use of tax revenues | 3.06 | 2.80 | 2.11 | 2.10 |

| Reducing government bureaucracy | 2.71 | 2.23 | 2.21 | 1.82 |

| Reforming the taxation system | 2.40 | 2.59 | 1.80 | 2.10 |

| Combatting unemployment | 2.82 | 2.27 | 2.10 | 1.71 |

| Providing youth with work opportunities | 2.66' | 2.25 | 1.76 | 1.66 |

| Ensuring energy supplies | 2.46 | 3.29 | 2.01 | 2.87 |

| Increasing the individual's determination over his housing | 2.86 | 3.08 | 2.32 | 2.49 |

| Strengthening the market economy | 3.37 | 2.69 | 2.72 | 2.15 |

| Strengthening the competitive position of business on the international market | 3.84 | 2.65 | 3.33 | 2.27 |

| Providing more favorable conditions for small and average-size industries | 3.38 | 2.75 | 3.01 | 2.38 |

| Balancing the budget and foreign accounts | 2.85 | 2.31 | 2.14 | 1.70 |

| Fighting inflation | 3.27 | 2.75 | 2.58 | 2.13 |

| Reducing power concentration in private hands | 2.45 | 2.40 | 1.95 | 1.76 |

| Reducing power concentration in public hands | 2.49 | 2.33 | 2.05 | 1.97 |

| Weighing in policy-making the wishes of business in a way advantageous to Sweden | 3.36 | 2.85 | 2.93 | 2.36 |

| Weighing in policy-making the wishes of the trade union movement in a way advantageous to Sweden | 2.80 | 2.71 | 2.15 | 2.04 |

| Preserving the welfare state | *) | 3.37 | *) | 2.60 |

|

Average score |

2.92 | 2.67 | 2.32 | 2.12 |

On the basis of the Government's scores in 1979 the voters renewed their vote of confidence in the non-socialists by a majority of only one seat in Parliament. The lower scores received this year indicate that the nonsocialists are facing a polling day that will be even more severe.

The present government not only has to try to overcome the ill will created by hard times. The government has mainly been formed by non-socialist politicians who had remained in parliament after 44 years of Social Democratic hegemony. The most talented members of the non-socialist bloc were never considered for government positions. As Social Democratic sway became extend. ed over time, they turned to the business community, to the military, to public administration, or to the universities. Thus the prolonged Social Democratic hegemony 1932-76 casts its long shadow over the elections of 1982 "The government has done as good a job as it could," says opposition leader Olof Palme, and the mild irony in his judgment is not difficult for the vote s to sense.

Mr. Fälldin, the incubent, has headed three governments during the past six years. He remained the key political figure in Sweden also after his.party was severely beaten in the 1979 election: it dropped from 24.1 percent of the electorate to 18.1 percent and lost 22 seats in parliament.

He is a vigorous and ardent opponent to nuclear energy – a paramount issue in his politics. He lost the nuclear referendum 1980 – obtaining 38.7 percent of the vote – but remained nevertheless as head of government. He is a clearheaded, resilient, and slow-speaking sheep farmer, totally non-academic. He has not made use of the usual paraphelia of politics: public relations teams, television appearances, public opinion polls. He uses his press secretarey more to keep journalists away than to feed them with his ideas. While he is more appreciated by the people than by the press his main effectiveness lies within the cabinet and the parliament than with the electorate. The public confidence figure obtained for him are bearish. However, he was generally considered the winner against Palme in the only televised debate during the campaign.

Mr. Paime, the leader of the opposition, unlike Fälldin, needs no introduction to an international audience. If you would ask whom he resembles most, Mitterrand or Papandreo, the answer will probably be Papandreo. The peers of his own choice among Europe's socialist leaders seem to be Kreisky and Brandt whom like his own Swedish mentor, Tage Erlander, are reformers first and foremost and keepers of the doctrine second. The public confidence figures for Palme in his own country are stable at a moderately high level.

The newly elected Conservative leader, Ulf Adelsohn, is a creative politician who before joining national politics developed a solid reputation for fiscal responsibility in the City Hall of Stockholm. The voters' confidence in him was, however, dealt a blow when he made an expensive weekend trip to the Carnival in Rio in the middle of negotiations with the Prime Minister. (Swedes are more puritan than their image!) Adelsohn nevertheless commands the public's confidence of a level twice as high as the Prime Minister and the Deputy Prime Minister, Mr. Ullsten.

The comparable confidence readings for Alf Svensson, leader of the Christian Democratic Union, is 6 percent, and the figure for Per Gahrton, the founder of the Environment party is 4 percent.

None of the non-socialist leaders approaches Palmels popularity as the voters' choice for Prime Minister. Thorbj8rn Fglldin, the present Prime Minister, makes a poor showing against Paime. Sifo asked: "if you compare Thorbj8rn Fglldin and Olof Palme, who do you think would make the best Prime Minister?"

Of our respondents, 63 percent favored Palme, 22 percent favored F311din, 6 percent thought there was no difference between them, and 9 percent answered "don't know". In the last election campaign 54 percent of those Sifo questioned had preferred Palme and 35 percent Fglldin: Palme has increased his lead.

In similar "contests" Palme now wins against Liberal leader Ola Ullsten by 62 to 20 percent, and against Conservative party leader Ulf Adelsohn by 55 to 30 percent. Ullsten had made a better showing in the previous election campaign (when he was Prime Minister) and had then lost to Palme 54 to 35. Adelsohn has succeeded in making the same showing against Palme as his predecessor as leader of the Conservative party, G5sta Bohman, did in 1979.

| Non-socialists | Socialists | All | ||||

| 1979 | 1982 | 1979 | 1982 | 1979 | 1982 | |

| Palme or Fälldin | ||||||

| Palme | 23% | 34% | 87% | 92% | 54% | 63% |

| Fälldin | 64 | 46 | 4 | 2 | 35 | 22 |

| No difference | 4 | 9 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Don't know | 8 | 10 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 9 |

| Palme or Ullsten | ||||||

| Palme | 11% | 34% | 75% | 89% | 42% | 62% |

| Ullsten | 68 | 41 | 6 | 3 | 37 | 20 |

| No difference | 9 | 14 | 10 | 5 | 9 | 9 |

| Don't know | 12 | 11 | 10 | 3 | 11 | 9 |

| Palme or Bohman(1979)/ Adelsohn (1982) | ||||||

| Palme | 25% | 18% | 93% | 88% | 57% | 55% |

| Bohman/Adelsohn | 61 | 65 | 1 | 3 | 31 | 30 |

| No difference | 5 | 7 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 |

| Don't know | 10 | 9 | 4 | 5 | 8 | 9 |

| Fälldin or Ullsten | ||||||

| Fälldin | 27% | 40% | 13% | 19% | 20% | 28% |

| Ullsten | 58 | 39 | 66 | 51 | 61 | 44 |

| No difference | 9 | 12 | 12 | 17 | 11 | 15 |

| Don't know | 7 | 10 | 9 | 12 | 8 | 13 |

| Fälldin or Bohman (1979)/ Adelsohn (1982) | ||||||

| Fälldin | 38% | 21% | 58% | 31% | 48% | 27% |

| Bohman/Adelsohn | 47 | 63 | 20 | 39 | 33 | 48 |

| No difference | 7 | 7 | 10 | 13 | 8 | 10 |

| Don't know | 8 | 10 | 12 | 17 | 11 | 15 |

| Ullsten or Bohman (1979)/ Adelsohn (1982) | ||||||

| Ullsten | 47% | 23% | 79% | 46% | 63% | 34% |

| Bohman/Adelsohn | 36 | 62 | 8 | 26 | 22 | 41 |

| No difference | 10 | 6 | 5 | 11 | 7 | 9 |

| Don't know | 7 | 9 | 8 | 17 | 8 | 15 |

Source: Sifo 82013/016

Fälldin has improved his position in relation to Ullsten, but Adelsohn wins against both Fälldin and Ullsten as the people's choice for Prime Minister. Among socialists, however, Ullsten is the first choice for Prime Minister among the non-socialist party leaders, and is the only candidate who receives any appreciable support from the opposing bloc.

The distribution of party votes according to Sifo is published monthly by four newspapers, each one supporting a different major party. The monthly report has a standard layout. Below is shown the poll from August 1982 published on September 4.

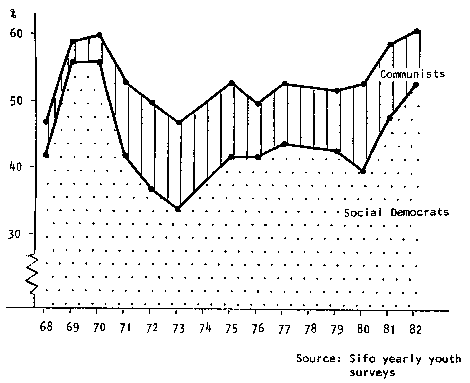

In the late 1960s a "red wave" swept over the younger generation in industrial countries. In 1968-1971 it swept over Sweden. Students, often the products of middle-class homes, were carried along by current, that divided the generations. When the wave crested 60 per cent of eligible voters under 25 yeares of age supported a socialist party.

Between 1972 and 197,9 the percentage of young people who sympathized with a socialist party was lower: in the trough of the wave the figures vary between 46 and 53 percent.

A new red wave has been gathering momentum since 1980. In 1982 Sifos annual youth survey noted a record high of 61 percent socialist sympathizers among those eligible to vote under the age of 25. Like its predecessor, the current wave is mostly composed of a growing number of Social Democrats. The Leftist communists and other communist fractions constituted a larger proportion of red youth in the trough of the late 19705.

Unlike the case in 1968, the new red wave has attracted young people who works as well as those who study. This time the non-students would appear to be in a majority. Unemployment is something they know about first hand.

The Conservatives maintain their share of young voters. The new red wave gets its strength from the weakness of the parties in the center of the political spectrum among the young. Party sympaties among 18-24-year-olds interviewed in Sifols youth survey between December 28 and January 30, 1980 are as follows:

| Conservatives | 24.5% |

| Liberals | 4.5 |

| Centerists | 8 |

| Social Democrats | 52.5 |

| Leftist Communists | 7.5 |

| Others | 3 |

Source: Sifo 82353

Blank Ballots and Election Day Boycotts

When election campaigns are mounted on the issues of socialization and cutbacks in the welfare state and most voters want neither the one nor the other it could not be surprising if many withdraw from the fray and either leave blank ballots or stay at home on election day.

We have a direct question that confirms a lower turnout 1982. It has been asked by Sifo in August prior to the September election in recent election years:

| 1973 | 91% |

| 1976 | 90% |

| 1979 | 91% |

| 1982 | 86% |

Source: Sifo 82034/035

In spite of the fact that the campaigns are being waged with larger resources than ever, the election to parliament may result in many blank ballots and/or lighter voter turnout than usual. The voters are not faced with dilemmas of the same proportions in municipal and county elections as in the parliamentary election, but there is a danger that the local will also reap a lower turnout since they are held on the same day as the parliamentary election.

Sifo has asked two questions in order to discern how the electorate is disposed in respect to blank votes and abstaining from voting.

421 non-socialists answered as follows:

| Abstain from voting | 9% |

| Cast a blank ballot in election to the parliament | 20 |

| Vote for one of the minor parties | 27 |

| Vote for the non-socialists anyway | 34 |

| Vote for the Social Democrats | 1 |

| Don't know | 9 |

425 Social Democrats answered as follows:

| Abstain from voting | 9% |

| Cast a blank ballot in electionto the parliament | 22 |

| Vote for one of the minor parties | 26 |

| Vote for the Social Democrats anyway | 20 |

| Vote for the non-socialists | 3 |

| Vote for the Communist Party of the Left | 1 |

| Don't know | 19 |

The dilemma of the non-socialist voter is resolved according to 29 percent of our respondents by casting a blank ballot or abstaining from voting, that which social scientists refer to as "exit". Accordinq to 31 pereent of our respondents the dilemma of the Social Democratic voter is resolved in like manner.

We also see that twice as many of our respondents chose to cast a blank vote as chose to abstain in the parliamentary election. In the 1979 election 31,000 persons cast blank ballots. This year the number will probably be greater.

Are The Minor Parties Jokers In The Game?

The answers to the voters' dilemma reported above also show a strong tendency to vote for minor parties. Almost as many as chose to exit elected the option to vote for one of the smaller parties: 27 percent of the non-socialists and 26 percent of the Social Democrats.

In order to view the minor parties in the right perspective let us turn to the 1979 election. The 4 percent minimum was then 219,000 votes. A total of 117,000 votes were cast for minor parties not in parliament. Of these, kds, the Christian Democratic Union, garnered the greatest number of votes, 76,000.

A rule of thumb is that a new party ought to be 2.5 to 3 times as large as old kds in order to have a realistic chance of getting into parliament. The Environmental party has never managed to attain such proportions in Sifols polls, nor has kds itself.

IMU, the pollster for Dagens Nyheter, gives the new Environmental party 6 to 8 percent in different polls. IMU is a beginner at opinions surveys and has never before participated in an election campaign. (IMU did take part in the referendum on nuclear energy and incorrectly found the opposition to nuclear energy, Line 3, to be the largest.) IMU has recorded a positive reaction to a new party name but not necessarily a genuine personal identification with a new party. For obtaining responses to a new party a pollster must be sure to record a phrase corresponding to "I regard myself as a voting supporter of the Environmental party" somewhere in the interview. The Environmental party has about 4,000-5,000 registered members, one third of which live in the Stockholm area. The percentages reported by IMU corresponds to 100 times this number.

In spite of unusually favorable conditions for minor parties in this campaign it is doubtful whether any of them will be able to surmount the high obstacle to getting into parliament the election law prescribes.

The Key Role of the Communists

Should the Social Democrats fail to reach an absolute majority and Communists not clear the 4 percent hurdle, a supporting party will be snatched from the Social Democrats if the Speaker asks them to form a government – this would be the case even if the voting were to result in a socialist majority.

The Leftist Communists have.had difficulties with their female voters. Their numbers have already declined under the 4 percent minimum.

Leftist Communists sympathizers among women:

| Summer 1981 | 5.6% |

| Winter 1981-1982 | 4.8% |

| Second quarter of 1982 | 3.5% |

The 1982 Swedish Election

*Forming a Government 1982

*Let's Look at the Record

*Part 4 – THE POLITICAL ACTORS

*Part 5 – PARTY VOTES

*The New Red Wave Among Youth

*Blank Ballots and Election Day Boycotts

*Are The Minor Parties Jokers In The Game?

*The Key Role of the Communists

*

Sifos INDIKATOR – Sifos politiska nyhetsbrev – ger opinionsledare och personer i ansvarsställning upplysningar om det rådande opinionsläget och förandringar i samhället.

Siffermaterialet är vanligen hamtat från Sifos s k veckobussar, de kontinuerliga intervjuer vid hembesök som Sifo gör två eller tre gånger i månaden på ett representativt riksurval av befoikningen i åldern 18-70 år. De baseras på 1 000 intervjuer. Om annan tidpunkt ej anges har intervjuerna gjorts veckorna före utgivningen. Om ej annat anges är de frågor som redovisas ställda på Sifos bekostnad och ansvar och gjorda enbart f6r Indikator

Sitos Indikator utkommer var 14:e dag fram till valet 1982, därefter sporadiskt.

Prenumerationsavgift: kr 2 000:- per år.

Ansvarig utgivare: Hans L Zetterberg

ISSN-nummer 0345-5262

Copyright (c) 1982 Sifo AB. Reprinted by permission.