VOLVO

OUTSIDE SWEDEN

An Executive Summary of the Volvo Monitor Survey 1983-84

In 1983-1984 Volvo Monitor interviews covered all major Volvo establishments outside of Sweden. It was a period of upturn in world trade in spite of strong projectionist overtures. It was also a period marked by a sharply rising US dollar. 1984 was a banner year for Volvo worldwide. This undoubtedly colors the results of the interviewing.

A total of 4840 interviews with Volvo employees were collected from Denmark, Norway, Finland, West Germany, Switzerland, Belgium, France, Italy, Scotland, North America, Brazil, Singapore, and Australia. In this summary analysis we have combined all operations in the same country with the exception that Penta in Italy is treated separately from Volvo Italia and Volvo White in the United States is treated separately from Volvo Corporation of America. The various plants of Volvo White (Greensboro, New River Valley, Ogden, Orville, and Columbus) are pooled in this summary. The Halifax plant in Canada collected interviews only from its white-collar workers and not from its blue-collar workers, and is, therefore, excluded from this summary.

In addition to the employee questionnaires information was collected in 75 informal interviews with managers.

This summary is not intended to do justice to the details of the situation in each country. (For that you must turn to the various country reports.) We will instead paint a broad picture and get an overall view.

Managers on the Volvo Philosophy

There is something special about Volvo - this can be heard and agreed upon in all countries where Volvo operates. However, Volvo executives around the world have a hard time articulating the special qualities that are Volvo. This difficulty is obvious also when they met a sympathetic interviewer. A typical manager rarely is able to go beyond statements such as "Volvo is safe and sound" meaning in one sweep both the Group's financial position, the products Volvo sells, and the operation of his own unit.

In some subsidiaries the Group's basic values and philosophy appeared rather unknown, in others very imperfectly known.

Management in still other subsidiaries could identify the "Volvo values" as articulated by the Head Office but noted that their particular unit was as yet unable to live in accordance with the Group's principles, and even questioned whether it should, in instances where such principles appeared to collide with local cultural norms.

Volvo's philosophy is sometimes described not in terms of the Volvo values but simply as being "Swedish". This is a characterization that has both positive and negative connotations. It frequently stands for "people-oriented," for example an attribute that is generally laudable if not "carried too far." Caring for people is welcomed, if not seen as an expression of a "socialist view, as is the case among Volvo people in some countries. The Group's personality and by this is usually meant impressions of middle management in Gothenburg is sometimes ascribed features that are stereotypically Swedish: slow, methodical, dull, thorough, and cautious.

How transportable are Swedish views on personnel, leadership, etc? To most managers interviewed, leadership development remains a problematic area. Some subsidiaries are most eager to get clear direction and Head Office backing for management development, while others express concern with the lack of articulation between their own views on leadership and those of the Group. In some countries, it was said, subordinates may feel more secure with a more hierarchic system and an authoritarian boss; for example, in Volvo White some (not all) complained that the organization was too "flat."

it was not unusual for local managers outside of Sweden to contrast the Swedish executive's group/committee approach and co-determination routines with their more individualistic manner. Explaining the backgrounds to decisions and giving those concerned an opportunity to voice their reactions to impending moves was thought by these managers to consume an inordinate amount of time.

Managers' Dependency on Gothenburg

The middle management in Gothenburg with whom the outside managers regularly deal are seen as good guys who are trapped in theft own world, about which they ask to few question. There is a welcome acceptance of headquarters views and procedures when they are based on superior analysis and understanding and practical experience. There is a reluctance to accept headquarter procedure that is seen as purely Swedish without any other redeeming quality.

When it comes to top management in Gothenburg, however, the profile changes: it is seen as bold, strong, and dynamic - all qualities that are personified in the person of Pehr G Gyllenhammar.

While this is admirable, a long-term corporate policy must eventually provide other ultimate bonds between the far-flung managers end headquarters than the charisma of the Chairman.

Utter dependence on Gothenburg is the unwritten premise for the managers in both the manufacturing and marketing subsidiaries. Here is a first psychological key to the understanding of Volvo outside of Sweden.

With the exception of Volvo White, the people working for the Group outside of Sweden owe everything baste to Gothenburg design, products, parts, delivery time, quality, prices, etc. This dependency is felt to be very asymmetrical. To be sure, Volvo in Gothenburg depends on its marketing companies abroad. However, with the exception of VAC in Rockleigh, the general feeling is one of poor leverage in dealing with Gothenburg. The psychology of this asymmetry is probably not fully understood by management in Gothenburg.

The relation between subsidiaries and the Gothenburg offices is a source of anxiety, sometimes anger, and always ambivalence.

Some subsidiaries (Volvo Far East and Volvo Trucks (Great Britain) are uncertain about Volvo's long-range commitments to them, an uncertainty reinforced by, for example, lack of capital investments. in such places there is a yearning for some sign of grace from Olympus in Gothenburg.

The Head Office is not only "where the action is" and the repository of Volvo knowledge, but is also the fountainhead of the Group's success. Most managers in subsidiaries would like to have a closer association with Gothenburg, to visit there more often, and have representatives from the Head Office visit them. Much like rivaling siblings, the subsidiaries want attention end evidence of an on-going interest from the Mother Company. Time and again one encounters expressions of disappointment at what is interpreted as Gothenburg's lack of interest in a company as long as it is doing well. This is when clear signs of appreciation would be welcome. One feels one deserves more attention! instead, one gets attention mostly when the company is having problems.

Yet one would prefer visitors from Gothenburg either to conform to the role of an ideal parent of a mature child, i e a parent who is concerned and supportive without being controlling and interfering, or to be clearly labeled as Junior brothers who are there to learn, not to lead. Also, like a good parent, one would like Volvo to respond without delay to requests; Just about every one of the subsidiaries complained about Gothenburg's painfully slow response time.

Some managers complain about what they see as a poor structure for managing Volvo corporate news. It too often happens that they learn about Volvo developments from a daily newspaper or a business magazine rather than from internally distributed reports, memos, telexes or other forms of communication.

Subsidiary manager's desire more opportunity to rotate to other subsidiaries, other countries, but this is perceived as the monopoly of Swedish management.

Managing the Consequences of Fluctuation in Local Markets

The second key to the mentality in the marketing subsidiaries is their response to fluctuations in their own. marketplaces. This response is much more complex than optimism in good times and pessimism in bad times. Once a marketing company has been through a couple of ups and downs a pattern seems to crystallize among its managers that sets the horizon for the company in both good and bad times. They develop either a consolidating mode or a dynamic mode.

One's view of the present and the future s, of course, greatly colored by past experiences. However, it is influenced not only by what one has experienced but also by how one reacts to it. It is not a simple one-to-one relation whereby favorable past circumstances automatically become harbingers of future felicity. The pessimist or the worrier may even react to good fortune with unease and say to himself nothings cannot continue to be this good." The optimist on the other hand may find in adversity an impetus to reverse his fortune. One man will regard change as a threat, another as a challenge. One manager will close himself to the uncertain future and withdraw into the smaller office or shop where he can create a stable, efficient world, the other will be open to the new day and go out to meet it.

The companies in a consolidating mode may be said to be in a process of premature closure, of turning inward in response to market fluctuations rather than meeting them head on. They seem to react to change like some chess players, who adopt a defensive posture and concentrate theft resources on consolidating their internal structure rather by breaking out and taking the offensive. The result can be preoccupation with guarding one's territory, stabilizing procedures, and on shoring up internal mechanisms to the extent that one's posture becomes too rigid for the market. The resulting structure is one that is too locked to be able to expand offensively and take advantage of opportunities when they present themselves. The commitment to work in such a climate may get high percentage points, but it is of a different quality than the commitment in dynamic companies. It is an energy-binding obsession with staying safe rather than an energy-releasing freedom of action. Most companies in the Volvo Group represent the latter, more dynamic mode. Here we find chess players who take advantage of openings and work actively to create these openings.

A Map of Volvo outside Sweden

Let us look in more detail at how the major Volvo companies outside of Sweden are coping with their human resources: We turn from the interviews with managers to the survey of employees.

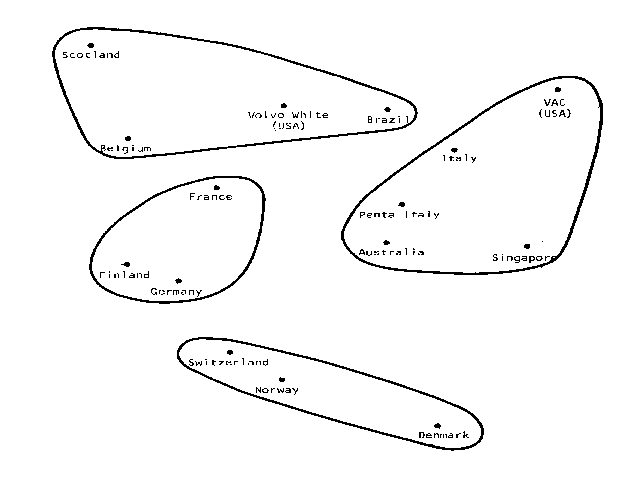

By cluster analysis |on the whole using the same variables as in the clustering of Volvo's domestic operations) we achieve the overview represented in Figure 1(1) This overview does not follow the official organizational plan. It is a matrix of distances. The criterion used is that differences between groupings should be greater than differences within the groupings on a large number of scores. Where such groupings are found they became "islands" on our map. We also want the distance between various units to represent measures of the differences we have discovered between these units. Although this is hard to achieve on a two-dimensional map the general rule is that the closer two units are on the map the more alike in their attitudes are the people working there. There is a great deal of difference between the attitudes of Volvo although they share a common language. There is a great deal of difference between the attitudes of Volvo in Denmark and Volvo in Ghent, Belgium, although the driving distance between them is short. The difference in mentality between VAC and Volvo Italia is small although a vast geography separates them.

There are three different clusters of marketing companies.

Group 1. The first group consists of Volvo of America Corporation, Volvo Italia, Italia Penta, Australia, and Singapore. The latter two are in the bottom part of the cluster, closer to the other groups of marketing companies. VAC and Volvo Italia are the more characteristic members of the group.

More than in the other Volvo units here studied, Group 1 personnel have the feeling that they work toward clear and common goals. They have a nearly boundless optimism about Volvo's future and more than other Volvoites outside Sweden they describe Volvo as successful. They feel more than others that it is easy to sell Volvo products and they show more pride in both Volvo products and Volvo service. They know that there are promotion opportunities.

The cluster analysis employed the same variables as in our clustering of Volvo's domestic operations. The model used is called NORMIX and was originally developed for the clustering of US Navy personnel. See J H Wolfe, "Pattern Clustering by Multivariate Mixture Analysis," Multivariate Behavior Research, 5, 1970.

Figure 1. Volvo worldwide clustered according to similarity of employee responses.

Most companies in this group have a management who are described as good listeners but also very determined; the leaders trust their people. The employees have, in most places, good relations to their local managers, and speak less gloriously about top management in Sweden than is customary in the Volvo group.

This Group is good to Volvo. Volvo Far East, however, does not have the momentum of its host economy. Volvo Australia is bothered by a gap between white- and blue-collar workers that should be resolved to release full energies. Actually, all conflicts within a company in this group should be resolved quickly. In no other Volvo units are the employees so ready and able to take Jobs outside of Volvo as in Group 1.

Group 2. This group consists of the marketing companies in France, Germany, and Finland. They have been less successful on the market in recent years than the Group 1 companies and have entered a consolidating mode.

On their positive side is a strong imbued work ethic: if you have taken on a Job you should do it and do it well. There is also a better-than-average feeling of being in the know about what goes on. And there is a sense that the Job requirements are in line with experience and abilities.

There is less reported independence and freedom on the jobs in Group 2 compared with the other groups, less feeling of being useful and productive, less appreciation of procedures for getting the work done, less cooperation between departments. The employees report less often than in other Volvo units that their supervisor consults them, and they do not think as often as in other Volvo companies that management notices when they put in an extra effort. The leadership is more often described as unimaginative and distrustful.

This group has an excellent potential for Volvo, but needs to be put into the dynamic mode. Each company in the group has activities in which this potential already is manifest. However, the average age of the employees is high and the median time they have served Volvo is long: 11.1 years in Volvo Deutschland, 9.1 years for Volvo Auto in Finland, and 6.9 years in Volvo France. The lower figure in the latter company may facilitate a process of change there.

Group 3. Within the Volvo world there is also a small convivial culture that appears in small nations where the social fabric is relatively unruffled untorn by major strife. Norway, Denmark, and Switzerland belong here.

The subsidiaries in these countries hold their own or make steady though somewhat unspectacular progress. The coworkers in these companies appear to excel in interpersonal relations. The social atmosphere at work Just couldn't be better: they feel they have a say in decision-making, they feel well-informed, that people care about them, they have good relations to their immediate (often inner-directed) supervisors and to management, and they work with people they like. But that is not all: they also have a rosy attitude toward their job, which they say is interesting, develops their potentials, is in line with their experience and abilities, and affords them a lot of independence. Their supervisors are open and inspire trust, as does top management. The only apparent wrinkle at these pleasant workplaces is poor cooperation between departments, but this is a nuisance they feel can be corrected. Not surprisingly, they want to stay with Volvo.

These job attributes would seem to describe the ideal workplace - if they were coupled with a robust drive to excel in the business world as well. This, however, is not regularly the case. It is as if these affable people have reacted to market fluctuations by flocking together and seeking comfort from each other, rather than by grappling with their problems. Whether by cultural orientation or individual disposition or both, they seem to put a lid on healthy aggressiveness and open zest for competition, preferring to be nice guys rather than ambitious and forceful. If you challenge them to a game of chess, they'll suggest having a cozy cup of coffee and a chat instead.

For Volvo Group 3 is a problem In spite of or perhaps because of all its pleasant qualities and their overload of humanistic Volvo values. These companies run the risk of losing their sense of business urgency and competitive drive at least the Scandinavian members in the group. They have a first-class management of human resources that is somehow waiting to be put to the big market test.

Group 4. This group consists of the production companies in Gent, Irvine, the Volvo White locations, and Curlttba in Brazil.

They are seen 4s providing reasonably good pay but not complete Job security. The employees feel they produce something important and that they serve the community. The Jobs are generally considered uninteresting and without independence but with good procedures for getting the work done and with good training provided by Volvo. There is good cooperation within various departments and between them.

Cultural Differences we may note in passing that the various companies in our cluster analysis do not divide according to cultural lines. Anglo-Saxon culture is represented in two separate clusters. The three Latin countries - France, Italy, and Brazil - end up in three different clusters. The four Anglo-Saxon entries - Scotland, the US with VAC and White, Australia - end up in two different clusters. And the five units from the Germanic world - Germany, Flemish Belgium, Switzerland, Norway, and Denmark are spread over three clusters.

The cluster analysis looks at relations and patterns between answers to interview questions and in this process other factors than cultural heritage become dominant, that is, organizational, interpersonal, and leadership issues.

Management Practice. A Model.

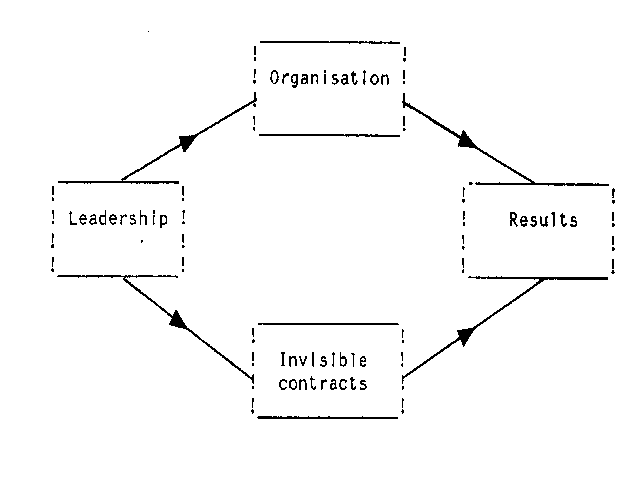

The Volvo Monitor Survey asks about matters we think are important to running a good business. There is a model of management built into this survey. This model is brought out in the reporting of results to each participating subsidiary, and its implementation is stimulated by local discussions, issuing from the survey results.

In simple terms this model of management can be represented by Figure 2.

Figure 2. Simplified Model of Volvo Management.

The starting point is leadership at all levels. This means that

| supervisors explain background | |

| supervisors ask the opinion of those involved | |

| confidence and trust develop in (a) the immediate supervisor, (b) local management, and (c) top management. |

Leaders have two interrelated tasks. The first is to make sure there is a functioning organization. This means to

| work toward clear and common goals | |

| efficient supervision of work | |

| cooperation within units |

The second task of leadership is to develop bonds between the organization and its members, what we have called the invisible contract, 8 mutual give-and-take between the organization and its employees. Here the leader attends to things such as -

| designing jobs that match the values of the employees | |

| giving everybody sufficient training for the Job at hand | |

| simultaneously developing (a) the employees' loyalty to the organization and (b) the organization's loyalty to the employee | |

| showing care and concern |

The organization and the invisible contract work together in producing results in the form of -

| economic gain | |

| ease in selling products and service | |

| good group spirit |

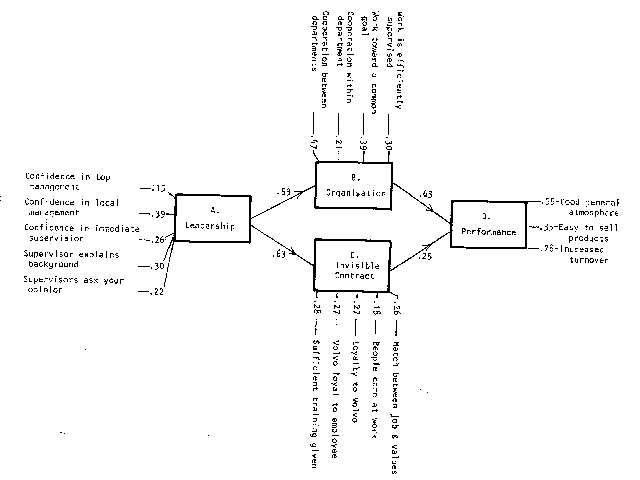

This model can be quantified by the data collected in the Volvo Monitor Survey. Various "manifest" indicators, i e answers to interview questions, in the survey are used to construct the key "latent" variables, i e leadership, organization, invisible contracts, and performance. (To measure the latter we also add data from the recent balance sheets.)

The result - calculated by Herman Wold's method - Is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Management Model According to LVPLS. 18 Volvo Units Outside Sweden

We first read the inner path coefficients. They clearly show that leadership indeed works through organization and invisible contracts. They also show, not unexpectedly, that over-all results are more closely related to good organization than to good Invisible contracts. But both, of·course, are needed for top performance.

We then read the coefficients between the items we have used to define our four main concepts. We see that they are all positive and contributing. Note in particular the high Importance of "working toward clearly defined common peals," and the high weight given to "good cooperation between departments."

Herman Wold, "Model Construction and Evaluation When Theoretical Knowledge Is Scarce: On the Theory and Application of Partial Least Squares" in J Kmenta & C J Ramsey (editors), Model Evaluation in Econometrics, Academic Press, New York, 1981. Our calculation is done by means of the computer program LVPLS 1.6 by J-B Lohmöller.

At Home and Abroad

Heedless to say, the many Volvo establishments abroad differ from the home establishments in Sweden. (For comparison we use the Volvo Monitor Survey in Sweden 1982-83, the 1984-85 interviews are not completely analyzed at the time of writing.) Taken as a whole, the assembly facilities in Belgium, Scotland, the US, and Brazil show an employee morale and dedication that is on the same level, and sometimes better then In the manufacturing facilities in Sweden. The Swedish Volvo plants may compare well to non-Volvo plants in Sweden, but not necessarily to the Volvo plants outside of Sweden. Seen strictly from' the point of view of employee morale and dedication there Is nothing self-evident about locating new Volvo manufacturing In Sweden, although this may be a good policy on other grounds.

There are also obvious differences between Volvobil, the marketing unit for the home market, and the Volvo importing and marketing companies in other countries. The mere difference in market shares makes all comparisons skewed. But looking again at employee attitudes and dedication one can find marketing companies that compare favorably with Volvobil in Group 1).

This points to a tough lesson for the home-based companies. They can learn much from Volvo outside of Sweden!

The survey reveals surprisingly large local variations. Volvo has not imposed a uniform corporate culture on its far-flung establishments nearly to the extent that IBM has. Differences In attitudes between Volvo employees in two countries may In fact be larger than the differences between attitudes in the two national populations. Thus the difference between Volvo France and Volvo Italia are, on balance, greater than the differences in a typical survey on values and attitudes In France and Italy. In the same way Volvo Deutschland differs from Volvo Suisse more than Germans and Switzerdeutsch normally do.

A closer study of human groups and societies usually turns up ambiguities, contradictions, and paradoxes. The Volvo community is, of course, no exception. Some of these can be resolved, but not all. Is it necessarily desirable that the Volvo Group presents a consistently uniform profile in its many subsidiaries and many parts of the world? One of the Group's continuing tasks will be determining its priorities - which contradictions or deviations from the norm it is prepared to accept and which it will find unacceptable for its business ends.

Copyright © 1984 Sifo AB and AB Volvo. Reprinted by permission of Sifo.