Seventeen Propositions about the Swedish Social State" from an anthology of Hans L Zetterberg’s papers entitled Sociological Endeavor. Selected Writings, edited by R Swedberg and E Uddhammar with an Introduction by Seymor Martin Lipset. European edition: City University Press, Stockholm 1997. US Edition 1998: Transaction Press, New Brunnswick, NJ 1998, pp 336-364. This chapter was an adaptation of the résumé in English (pp. 289-306) of Vårt land, den svenska socialstaten by Hans L. Zetterberg & Carl Johan Ljungberg, a final report from a research program sponsored by The Swedish Free Enterprise Foundation and coordinated by City University in Stockholm. Copyright ã 1997 by City University Press and the authors and reprinted in Sociological Endeavor by permission of Carl Johan Ljungberg.Originally called "

Original page number have been added to this text. Numbers in brackets [p 0] refer to Sociological Endeavor. Numbers of propositions (0) refer to Vårt land, den svenska socialstaten and s 0 stand for page reference in the latter book.

[p 336]

We cannot avoid welfare arrangements. People who cannot cope for themselves are found in every society that lasts more than a generation.

| Both past and present societies have four universal welfare populations: the very young, the sick or handicapped, the elderly, and the destitute. There are, moreover, special welfare populations in all modern societies, above all the unemployed. | (1)s23 |

Following Arvidsson, Berntson and Dencik (1994), we use the term social patronage for the support given to welfare populations. A state's commitment to welfare populations can vary from minimalist to maximalist. A state with a large social patronage is defined as a welfare state or social state. We use these terms synonymously but prefer the latter in scholarly reasoning since government patronage often has consequences other than simply "welfare."

As in other countries, the modern Swede pays taxes in order to obtain public protection of life, limb and property. But he has also been promised, on an ever wider scale, a living standard that is guaranteed by the state as well as a kind of state support at the crossroads and difficulties of life that assumes a scope and form typical of the Scandinavian countries. A modern Swede can hardly imagine himself apart from his welfare state without having to redefine his self-image and his own national identity. An internationally known Swedish economist calls the welfare state, not just a historical stage among many others, but a "triumph for the modern civilization" (Lindbeck 1993, p 98).

Kristersson (1994) describes how Swedish social legislation has evolved during the 20th century. Like a mountain creek it starts out at the turn of the century with the establishment of the principle of universal welfare and basic security in the Public Pension Act of 1913; it maintains universal welfare with an income protection principle in the Industrial Disabilities Act of 1916. Slowly it gathers into a stream, establishing income protection at unemployment in the 1930s. It widens to a river [p 337] after the Second World War with General Health Insurance and Child Benefits in 1947, Supplementary Housing Allowance in 1952 and Supplementary Pension (ATP) in 1959. It forms at last a mighty torrent with Parents' Insurance and Dental Insurance (1973), Partial Pensions (1975), and, finally, the Social Service Act (1980) which set up local Welfare Offices with the ultimate responsibility of insuring that everyone within a municipality had a decent living standard.

The social state is an international phenomenon.

| The transition from an agricultural to an industrial society resulted in new forms of social patronage, although its development did not follow a uniform pattern but was determined by the history, traditions, values as well as the power structure of the respective nations. | (4)s50 |

The transition prompted legislation for the welfare populations: child benefits, disability insurance, health insurance, old age pensions and unemployment insurance. In the case of Germany, Great Britain, and Sweden (representing three different European models of the social state) public assistance to the welfare populations was introduced in the same order of priority. First came pensions to the elderly, then support for the sick or those suffering from disabilities incurred on the job, then the unemployed and, finally, the young. Other countries have had different priorities, particularly the United States where mother and soldiers were protected before the workers. (See chronologies in Skocpol 1992, p. 9, or in Hicks, Misra & Nah Ng (1995 p. 337.)

The present transition from an industrial society to a global neo-industrial one based more on service and electronic communication will in turn presumably result in new forms of assistance to the welfare populations. So far, during the 1980s and 1990s, we have mostly seen a general retreat from state-run welfare in richer nations (Stephens, Huber & Ray 1995). In Sweden, for example, compensation levels for unemployment, sickness and parental leave have decreased during the period 1990-1995. Decisions have been made to lower retirement pensions and housing allowances. Early pensions and disability compensation have become more difficult to obtain. The list goes on. The inventive new features of welfare suitable to a neo-industrial order are less evident. HMOs (health maintenance organizations) in the USA and Provident Funds in Singapore can be cited as social innovations suited to a neo-industrial society.

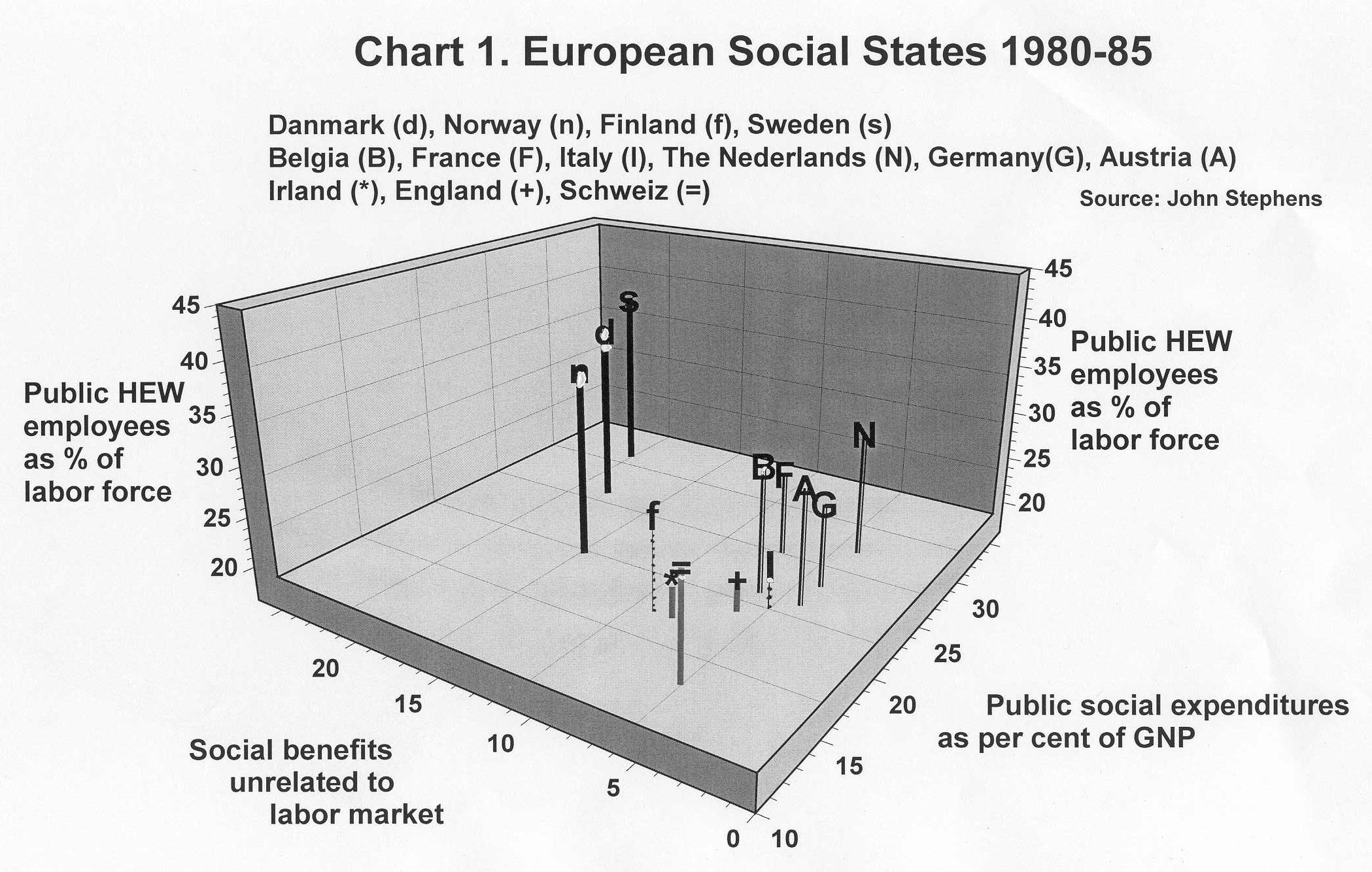

The size of the social state should not be estimated only as the welfare budget's share of the BNP. Also to be taken into account are the numbers of governmental employees involved in welfare service and how generous the system is in allowing people benefits without participating in the labor market, what is know as decommodification (Es-[p338]ping-Andersen (1990). With these three variables we distinguish three clusters of European welfare states in Diagram 1.

[p339]

| The Nordic model. Here the welfare states are maximalist and decommodifying and have many public employees in the delivery of welfare services. Denmark, Norway and Sweden belong in this group. | |

| The Continental model. Here the welfare states are maximalist, fairly decommodifying, and have few public employees in the delivery of welfare services. Subsidiarity prevails in such a way that public welfare comes in as the last recourse, usually financial rather than operative. Belgium, France, the Netherlands, Germany and Austria belong here. | |

| The Anglo-Saxon and mixed model. Here the welfare states are more minimalist, commodifying, and have few public employees in the delivery of welfare services. Ireland and Great Britain belong here. England's former colonies also belong here, but we limit our study to Europe. |

The Continental social state is not cheaper than the Nordic with its top-down approach. It does, however, allow for a somewhat greater role to be played by the market and the civil society before the state gets fully involved.

Most research inside Sweden on the Swedish welfare state blissfully and tacitly takes its point of departure in those values of popular rhetoric which have come to dominate within the department and the institutions of public welfare and in the unions whose members man the welfare state. Swedish welfare researchers and their funding agencies as well as welfare politicians usually hold that any measures aiming at equality by means of rights guaranteed by the state are good (Kangas 1991). In our own research the underlying value premise has been that anything adding to human dignity is to be considered valuable, even if it does not always imply equality.

The term social patronage (or some synonym) is totally unknown to the Swedes. But such a term is necessary for an analysis of their situation. The term implies that support routinely can come to the welfare populations from parts of society other than the state. This is, however, beyond the cognitive horizon of most Swedes, a fact that results in nearly total support for the existing welfare state in public opinion polls (Svallfors 1992). Virtually the whole public debate in the second half of the 20th century is whether state support is sufficient or not.

It is not against the law in Sweden for associations and families in civil society to give relief to the welfare populations. Nor is it illegal for people to invest in private health insurance or pension plans. Again, it is not illegal to visit a private [p340] doctor or dentist. However, the ambition of the Swedish social state for the second half of the 20th century has been to make such procedures unnecessary. A Swedish member of a welfare population should not have to depend on his relatives, private charity, or the market. Governmental arrangements should suffice and be of such high quality that the alternatives become unattractive. This is the Swedish welfare doctrine, a doctrine of full service from the public sector to the welfare populations.

Against this doctrine we propose a tripartite doctrine that will be specified at the end of this paper. It is self-evident in most countries, but not in the Nordic ones:

| Welfare populations will have a more dignified life in return for reasonable investments from the whole of society when an optimal division of labor in social patronage has been achieved between civil society, the state, and the market. | (2)s23 |

In the face of a problem for a welfare population, we should not, as the Swedes do, only and immediately ask: What can the state do? We should also ask: What can the market do? What can civil society do?

Welfare populations actually begin from a strong position in the normative system of civil society. To give aid to children, sick, elderly and poor is an obvious, normal and expected reaction in civil society. These ideas live on, even in the most developed of welfare states. Karin Busch Zetterberg (1996) found that Sweden in 1994 had 450,000 men and 560,000 women who were "taking care of a sick, handicapped or elderly person" with no assistance at all from the local government. As we see it, it is an abnormality when such numbers are read as a measure of the failure of welfare!

The welfare populations have, by contrast, a weak position in the marketplace; they are quite simply short of money. Most children have few assets. The sick, especially the chronically ill, can be quickly drained of their savings. The elderly cannot renew their assets by returning to the labor market. Low-income earners can, of course, be actors on the market. There are entrepreneurs who specialize in developing and selling articles and services to low income earners. Less so in Sweden; affordable housing, for example, are governmental projects.

Social insurance schemes have become the welfare state's universal recipe for strengthening the position of the welfare populations on the market.

[p341]

In the 19th century needs-tested poor relief was the major welfare program. It did not treat its clients with dignity. The welfare clientele did not enjoy full rights of citizenship. In 1918 a new law came into effect for case-tested municipal relief to the poor which put an end to the practice of having local authorities act as legal guardians for the recipients.

Already by the 1910s, however, other principles for Sweden's social insurance policies had been put into place. As early as 1913, the 19th century conception of old age insurance had begun to be replaced by the principle of equal welfare in the form of the public pensions (analyzed by Elmér 1960). In 1916 the principle of loss of income compensation was introduced in an insurance against industrial disabilities (analyzed by Edebalk 1993). These programs were administered and financed by the public sector, not the private. Both the principle of equality in public pensions and the loss of income principle in disability insurance were universal, what the Swedes came to call generell socialpolitik and not dependent on case-testing. In Diagram 2 we illustrate three avenues -- case testing, basic coverage, and income protection -- along which Swedish social insurance has developed.

|

Chart 2. Major Avenues of Swedish Social Insurance Paradigmatic legislation from the 1910s and some later applications |

||||

| Case Tested Programs |

Universal Welfare Programs |

|||

|

1871 Poor Laws |

¯ |

¯ |

||

|

Equal coverage |

Income protection |

|||

|

Paradigmatic law: 1918 Poor Laws |

Paradigmatic law: 1913 Folk Pension |

Paradigmatic law: 1916 Industrial Disabilities Act |

||

|

¯ |

¯ |

¯ |

||

|

¯ |

¯ |

¯ |

||

|

¯ |

¯ |

¯ |

||

|

¯ |

¯ |

¯ |

||

|

¯ |

Child allowance |

Unemployment compen-sation (a-kassa) |

||

|

¯ |

¯ |

¯ |

||

|

¯ |

Unemployment stipend (KAS) |

Sick pay |

||

|

Housing allowance |

¯ |

¯ |

||

|

¯ |

Study grants |

Supplementary pension (ATP) |

||

|

Welfare cash |

¯ |

|||

|

Parent insurance |

||||

[p342]

The Swedish arrangements to cope with unemployment fall into two of the columns of the diagram. Unemployment insurance (a-kassa) as an arrangement for income protection is not completely universal since participation is voluntary; in the 1990s it covers about two-thirds of the labor force. It is managed by the labor unions, but the state pays almost all the expenses (as in the Continental model). An unemployed person who lacks unemployment insurance can still receive cash unemployment compensation (KAS), i.e. reduced benefits in the form of a fixed basic security payment granted upon application.

A new principle to create equal opportunities for higher education by means of benefits attached to personal repayment obligations was tested in the 1960s but only on a small scale. In all the essentials, the three major forms of Swedish social insurance -- case tested, basic coverage, and income protection -- already existed in the non-Socialist decade of the 1910s.

Case-testing has high transaction costs since it requires individual bureaucratic decisions for every payment. In line with the reasoning developed by Coase (1937,1960), we may state:

| As the state's social patronage grows in scale, it is more and more formulated as universal (not case-tested) assistance to the welfare populations. | (5)s65 |

In certain instances, however, case-testing does survive even in Sweden's universal welfare policy. A line runs from the Poor Relief Act of 1918 to the housing allowances of the 1940s, the Social Assistance Act of 1956 and the Social Services Act of 1980 which offers to all "a decent living standard". The right to welfare benefits has become clearer and the benefits have become larger, but needs-testing or income-testing remain in these welfare programs. The consequences have sometimes been bizarre, as Rivière (1993) has shown. She recounts, among many other things, a story about a drug addict who requested the help of Social Services in paying off old drug debts of 124,000 SEK. The request was rejected, but the man appealed to the Administrative Court of Appeals, which agreed to the payment, citing the Social Services Act.

Uddhammar (1997), using data from the national welfare rolls, follows welfare recipients for nine years (1982-1991) and demonstrates how welfare benefits interact with short and long-term exploitation of other benefits such as unemployment [p343] compensation, housing allowances and sickness benefits. Such a dynamic view of welfare recipients of working age (18-64) has not been previously available. In a cluster analysis he finds that within the "working ages" from 18 to 64:

| 57.7 per cent are gainfully employed (long-term as far as can be seen) and receive either no benefits or only very temporary ones; | |

| 17.6 per cent are gainfully employed with fairly long periods of unemployment benefits and/or sickness benefits; | |

| 5.8 per cent receive benefits as chronically sick and/or unemployed but do not receive supplementary benefits, with one in three on an early pension; | |

| 15.0 per cent remain outside the labor market as students, early retirees, housewives/househusbands, and at times receive various temporary benefits; | |

| 3.9 per cent are incapable of supporting themselves on the labor market and are long-term dependents on supplementary benefits and housing allowances. |

Interviews in 1995 indicate that about half, 49 per cent, of Swedes of working age receive some social benefit payments: child allowance, student allowance, housing subsidy, unemployment benefits, sick pension, in this order. But a much smaller percentage become totally dependent on state benefits. Correcting for early retirees who in interviews say that they both can work and want to work (36 per cent according to Berg et al 1997), we calculate that about seven per cent of working-age Swedes 1985-1995 are almost helplessly dependent on the social insurance system. You may say that this is the human price tag for living in our kind of society.

A major step towards equal and universal welfare was taken in 1913 when Swedish farmers received the same retirement benefits as industrial workers. The German concept of worker compensation was rejected and an old age insurance scheme was adopted for the entire nation, folkpension. The idea of benefits "equal for everyone with no individual testing" became one of the cornerstones of Swedish political praxis and rhetoric. It is what today would be called a socialist principle, even if it was acceptable to all the large vested non-socialist interests of the time. [p344]

Welfare programs in Sweden are not always motivated by the needs of the welfare populations. Sometimes this is quite explicit. For example, the rationale behind housing allowances is not just to offer the welfare populations a roof over their heads: they are also indirect public grants to the building trades and the construction unions for new housing construction. Sometimes this is hidden from view. In an echo of Pareto (1993 [1901] we may state:

| The development of public social patronage to the welfare populations usually runs on the fuel of concessions to major interest lobbies, but its lubricant has been ethical considerations with humanitarian overtones. | (6)s74 |

Without fuel, a motor won't get anywhere, and without lubricant it jams. In the entire welfare debate of the 20th century we find that social reforms result from a political fight over each group's share of the collective resources, although the debate itself is mostly pursued on the moral level. Reforms are presented as the result of a general humanitarian drive. Greed (or shall we say "rent seeking" in the vein of Tulloch 1989) may be the fuel, but the language of compassion is the lubricant. However, only the unselfish aspects are usually recorded for posterity.

Belonging to the social welfare legacy of the non-Socialist 1910s is the principle of compensating loss of income. In its day it was an ingenious social invention. With that in his bag a person could openly compete for better jobs and higher wages in the new industrial, urban society. The wages he attained at one stage were guaranteed up to a certain percentage by the state. Even after accidents and other misfortunes, he could still return and obtain a new, perhaps higher, salary, which in turn would again be guaranteed by the state. This arrangement could meet the conservative demand of maintaining status and rank, i.e. the accustomed standard of living, as well as the liberal demand of life chances, for example, constantly improving one's living standard. In the event of misfortune, an income guarantee permits a person to maintain his standard of living, whether high or low, thus providing an antidote against discouragement. Income protection gave Swedish capitalism a human face. As a social insurance principle it gave more to the middle classes than the working class. (Therborn 1989).

In the Industrial Disabilities Act of 1916, previous salary and wage levels determined the levels of compensation. In this way it differs completely from the Public Pension of 1913. [p345]

| The State's universal social patronage can be formulated either as basic coverage according to the principle of equality or as income protection according to the principle of dignity. The latter solution is more compatible with the market. | (7)s81 |

State-run social patronage is most effective when compatible both with the market and with civil society. Greatly contributing to this compatibility have been active efforts to try to bring the unemployed back to the job market.

Legislators with an egalitarian bent can massage income protection schemes by lowering ceilings and raising floors so that they result in fairly equal outcomes. This happened in Sweden after 1968.

During the latter decades of the 20th century in Sweden, two different forces, eroded the principle of compensating for loss of income: the supporters of decommodification, on the one hand, and the supporters of equality, on the other.

In the former case, there was a leftist desire to liberate people from the job market, i.e. to allow them to attain an acceptable living standard without having to work all the time.

In the second case, the idea was that social welfare should help to advance equality. Borg (1992) offers a series of examples of this from various areas of social legislation. Especially after 1968, equality becomes the by-word in Swedish social undertakings and welfare no longer means merely providing relief to the welfare populations of young, old, sick, unemployed and destitute. It was one of the signs of the times when Swedish sociologists (Korpi 1983, Korpi & Palme 1993) began to gauge the success of public welfare in Gini-coefficients, i.e. by measuring the gap between rich and poor, rather than the effectiveness of humanitarian measures for the suffering.

"It is most fair if everyone gets the same", says the Swede in one breath, speaking the language of 1913 on basic coverage. "It is most fair if those who have lost more or worked or paid more also get more", says the Swede in the next breath, speaking the language of 1916 on income protection. But you cannot have it both ways:

| The principle of basic coverage and the principle of income protection are dissonant in a social state, and when it seeks to house them both, it becomes unstable: the incompatible elements may at first be hidden in [p346] words, but, sooner or later, one of the elements comes to dominate the others so much so that it minimizes the dissonance. | (8)s90 |

The Swedes hide the dissonance by using the umbrella term "universal welfare" (generell välfärdspolitik). They hide it by using different bureaucracies to deliver basic coverage (e.g. KAS) and income protection (e.g. a-kassa). Our recommendation is that in the choice between income protection and basic coverage in social insurance policies, income protection should be chosen if possible. It is more compatible with the market and gives capitalism a human and dignified face.

Proposals for new social insurance plans in Sweden in the 1990s are all connected to the opportunities created by large-scale computerized accounting methods and are based on the idea that the state could or should act as the accountant of its citizens.

One solution is financial welfare service based on repayment obligations. It was first used in the allowance system of the 1930s for single mothers with children and later in the student financial aid of the 1960s which was part-scholarship, part-loan. The latter system was liberal in the specific sense of (1) offering everyone the help of the state in improving their opportunities, but (2) allowing each person to bear his own responsibility for carrying out his plan of life and (3) repaying the government, if successful. In the 1990s this type of support has been tried on a small scale to help arriving immigrants.

Since all benefits today are registered by the state, there is in theory a simple way of introducing the repayment principle into the whole social security system: through "claw-back taxes" by which the state "claws" back the benefits from those who do not need them. This would add an extra line to the income tax form on which the authorities have filled in the sum of received benefits. The sum would be taxed according to a special tax table. People with very large incomes from other sources would keep only a token benefit. The effect on universal benefits would thus be roughly the same as if the benefits had been selective and means-tested. The "clawing back" would enhance the targeting of the benefits and counteract possible overuse.

Other proposals being discussed but not implemented in the 1990s are tax-deductible deposits into "citizen welfare accounts" where the state commits itself to track the citizen's individual deposits and withdrawals made for welfare purposes (Fölster 1994). Assets on deposit (and advances granted) could be disposed of at the citizen's discretion for approved purposes such as education, purchase of [p347] housing, sabbatical leave, parental leave, sickness benefits, unemployment relief, pension etc. Relatives and others might also be allowed to make tax-deductible deposits in a citizen’s welfare account.

Even if compensation for loss of income has been the most effective tool of Swedish social security, it now has to be modified. The basis for all the social insurance policies of this type ought to be a running average of the reported income for recent years. A by-product of such a proposed change in the basis for loss of income insurance would be the increased incentive to report all income. Tax fraud would incur its own punishment in the form of lower welfare payments.

Employees in public social patronage form three groups: (1) business personnel in the nationalized corporations within the social welfare sector, (2) administrative bureaucrats and service workers, and (3) specialists and technocrats. The service workers dominate the personnel statistics in the Nordic welfare states. Women once bore most of the responsibility for the universal welfare populations (children, the sick, the elderly). As the state increasingly took over social patronage, women still performed the work inasmuch as they made up a disproportionate share of employees in the welfare establishment (Antonen 1990). In spite of Sweden's commitment to equal rights, an overwhelming number of women seem stuck in lowly paid jobs in the public social sector. They can not readily compete with their counterparts in Western Europe in level of education and opportunities for securing executive positions (Lignell Du Rietz 1994).

The nationalized companies in the welfare establishment include, among others, municipal housing corporations, Systembolaget, a retail monopoly for alcoholic beverages; Samhall, an employer of handicapped persons, and the Labor Market Board which carries out labor market initiatives and job training. Among the administrative bureaucrats we can distinguish a qualified category of "public officials" (ämbetsmän) who are well-educated and legally accountable. In the social state, however, traditional bureaucratic expertise is replaced by a so-called street-level bureaucracy that grants extensive powers to its functionaries, mostly in the handling of case decisions (Lipsky 1980). We believe it to be a general problem affecting, among others, the welfare sector that the traditional role of the public official in Sweden has for some decades now been replaced by lower administrative bureaucrats who carry out political decisions with less regard to competence, objectivity, impartiality, and self-control.

Industrial workers, employers and farmers profited from the first public pensions. The middle class benefited the most from the various income protection [p348] schemes. In time another vested interest, welfare managers, emerged. The welfare managers are powerful not only in respect to their clients but also in respect to the people who appoint them.

| Under state-run social patronage of the Nordic model, concessions to the interest group of welfare bureaucrats and functionaries are growing faster than the benefits to the welfare populations themselves. | (9)s128 |

According to Percy Bratt (1996), modern Swedish legislation in its development since 1945 and its culmination in the 1970s reflects a view of man with distinct features of environmental determinism. The individual is not presumed to be capable of complete personal responsibility for his social conduct. Instead, the state is to improve the social environment through reform measures. This idea of social determinism combined with a faith in equality is the key to the laws, regulations, welfare and penal institutions of present-day Sweden. The rules of law, legal stability, personal responsibility and privacy have been neglected to a corresponding degree. Punishment fell out of fashion, and was often replaced by therapy.

For some years now, however, a return to a more classical view of personal responsibility has been taking place and judges are once again attempting to define the principles for accountability and intervention. Lawmakers and the courts appeal now more frequently to the individual's free will and moral awareness, a trend that will probably have repercussions in the area of welfare politics.

The Swedish social state entails far more than social insurance. It includes also welfare services in natura: prenatal care clinics, day nurseries, after-school recreation centers, job centers, welfare offices, hospitals, homes for the elderly, other municipal housing for the elderly, et cetera. It is this tax-financed production and delivery of welfare services that results in the high number of government employees in the Nordic model of the welfare state.

The ideal under law is equal treatment, uniform service in kind. To treat all equally is, naturally, easier if the citizens are also all equal.

| Public social patronage to a homogenous welfare population is effective and legitimate if administrative bureaucrats who treat everyone equally according to the rule of law deliver it. | (10)s140 |

[p349]

Non-cash services become difficult to manage as soon as the welfare client groups cease to be homogenous. When administrative bureaucrats try to implement the Swedish special welfare legislation for immigrant groups, the system breaks down because the immigrants are extremely heterogeneous (Gür 1996). Since present-day needs and demands have become very diverse also in many other welfare populations, one possibility would be to give the citizens their pick of a public storehouse of welfare products of roughly equal value to be paid for by welfare vouchers. This is called an "IKEA model" by Arvidsson, Berntson and Dencik, (1994, pp. 347-351). However, it is an untried option.

The oldest welfare institutions are for health and dental care. Yet the sick do not make up a homogenous group: they are united only in being sick, i.e. excused from some normal social obligations. Medically speaking, there is heterogeneity among them. They all need individual diagnosis and treatment. Can a state committed to equal treatment of everybody provide this? Yes, if the task is delegated to the doctors. They represent a qualified kind of specialists we call "professionals". They have a monopolistic hold on their profession and academic discipline as well as a collegial professional organization; they take their cues from colleagues rather than from political and administrative superiors. The ultimate determining factor of the vitality of health care is the professional relationship between doctor and patient, not its outer administrative framework.

The professions are much better suited to deal with heterogeneous welfare populations than the administrative bureaucrats.

| The state's social patronage to a heterogeneous welfare population can be effective and legitimate if welfare politicians delegate the delivery of services to a profession. |

(11)s147 |

The doctor may at his discretion give one patient an expensive treatment or an inexpensive one. He is bound by professional practice to treat all patients, but to treat them, not equally, but differently according to their medical needs,.

This idea works well in medicine but does it fit social work?

Like the medical doctors, most social workers in Sweden (over 80 per cent) work in the public sector. As a predecessor to welfare service, the deacons made up a professional group with training in theology and a practical knowledge of humanity who treated people with a spirit of Biblical charity on an individualized basis. Politicians on the right, especially Gösta Bagge institutionalized secular social workers as an occupation in Sweden in the 1940s (Andreen & Boalt (1987). The social worker was, [p350] in his conception to act as a legally accountable municipal official with certain amount of schooling in psychology.

As a service provider according to the Social Services Act of 1980, the role of the social worker has become less defined as a public official and more elevated as a professional with a wide area of discretion to act according to a practice defined by colleagues rather than legislators. However, these colleagues do not have much of established academic disciplines to lean on, so they are often left to personal judgments regarding the cases at hand. When municipal social workers remove children from their alleged problem-laden biological parents they forecast a better life for the children. But no social science can make this type of forecast with any certainty on an individual level. The result may be good, but it may also be a tragedy (Nowacka 1991). The Swedish social worker in public service is de facto neither a very good public official, nor a very good professional (Carlsson 1995). Of course, the welfare architects are to blame for this state of affairs, not the social workers, who are distressed by their unclear role (Frankel 1991).

We recommend that the government distinguish more clearly between health care and welfare service and have greater respect for their different degrees of professionalisation. Professors in social work and their colleagues in relevant disciplines ought to be given a key role in defining decisions by social workers that they can make as independent professionals on scientific grounds (see, for example Turner 1995). Where there is insufficient scientific basis, the role of social workers as government employees subject to law should be emphasized and their decisions made only according to specific rules determined by Parliament.

The democratic state and the social state must be clearly distinguished. One can favor the welfare state without being for democracy. One can also be against the welfare state and still for democracy. Nevertheless it is often reasonable to hold that the grounding of democracy in our century in most cases is promoted by the allure of public welfare (Flora & Alber 1981, Linz & Stepan 1996).

Although the thought is unpleasant, it must be articulated all the same: welfare policies can become a trap for democracy. If the expenses of welfare reforms exceed the income and borrowing capacities of the state, crises can arise to the detriment of democracy (Langby 1984). An obvious example is the apparently vital democracy and social state that prevailed in the Weimar Republic. As politicians tried to finance overblown welfare promises and other commitments, the government printed more and more money with the result that inflation ran rampant. [p351] Meanwhile assets were also being diminished in the depression of the 1930s. In that situation the Germans voted in Hitler and the Nazis.

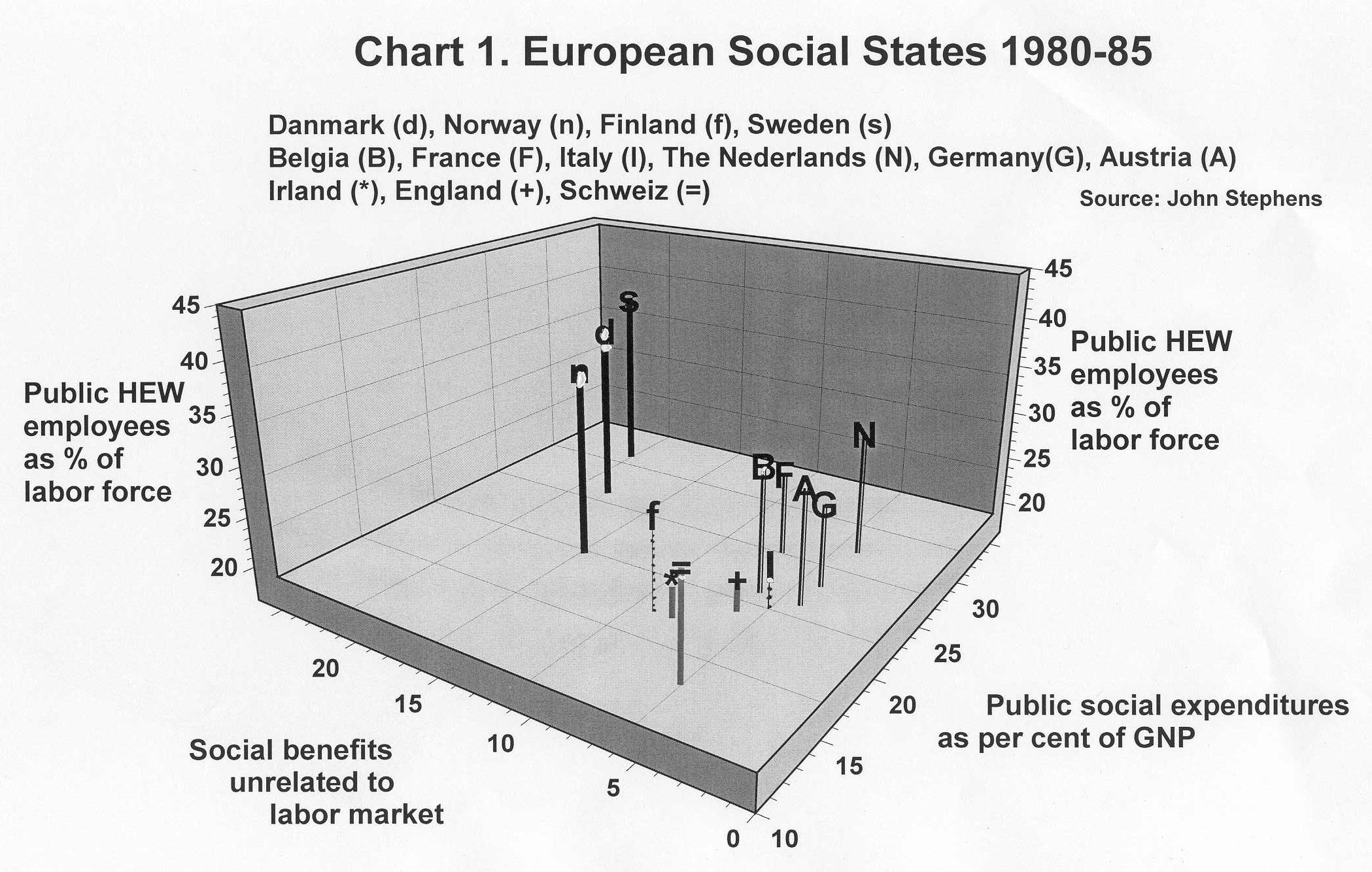

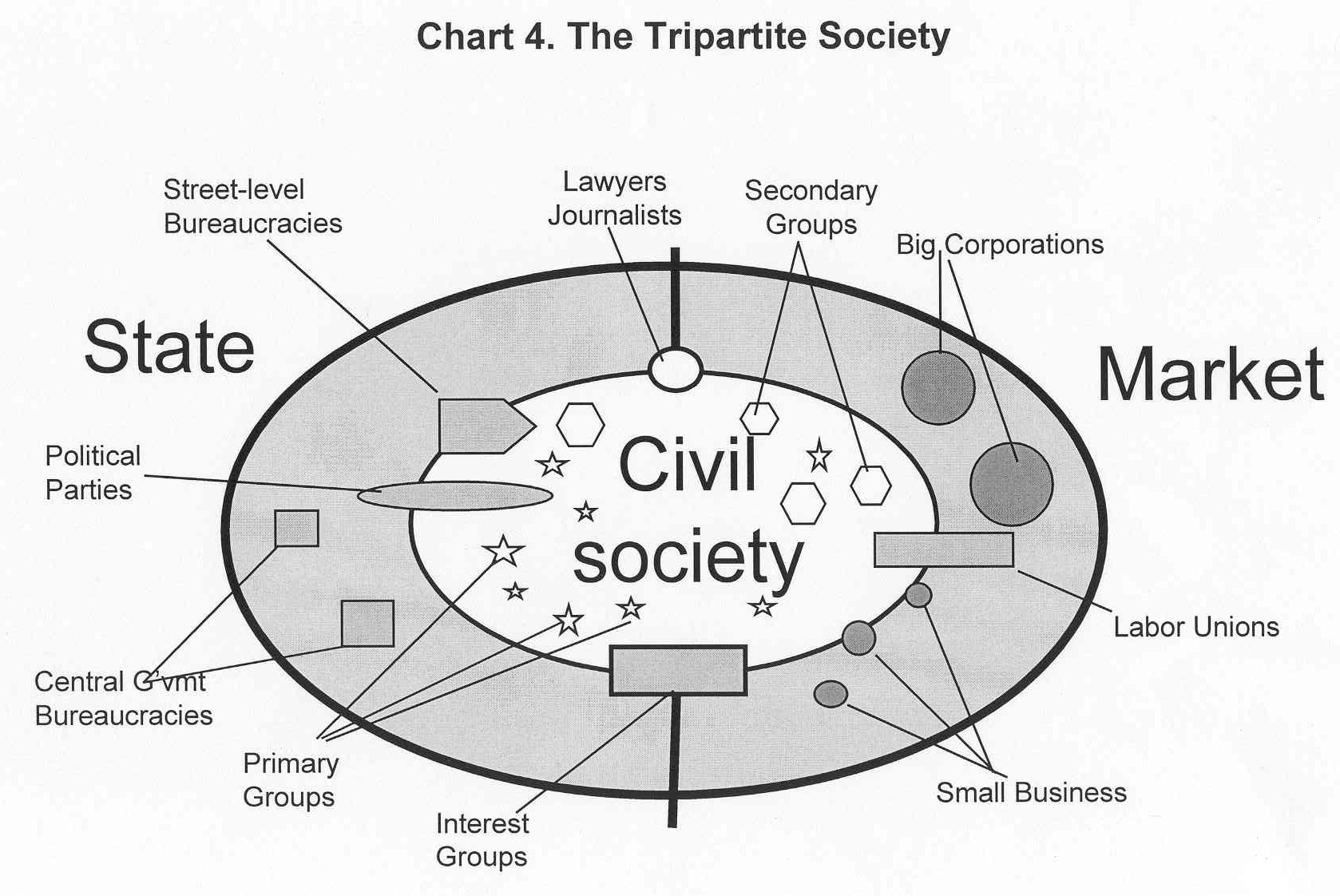

The Swedish (and Danish) situation illustrates another type of challenge that the social state poses for democracy. Most household income (counted in crowns) emanate from work, not from social benefits. But a high proportion of the population (counted in persons or voters) receive income also from the welfare systems. Diagram 3 gives a unique X-ray picture of the sources of personal income the Swedish social state in 1994.

[

[

[p351]

Employees in the public sector and the clients of the state are in absolute majority in the electorate. This is a situation the fathers of democracy never had cause to ponder. The very thought that the public sector would grow so large was beyond the horizons of their imagination. Their reasoning was based on the premise that the state is in the hands of a minority, and that only a minority can live off the state. The problem they addressed was how to control this minority and ensure that it followed the will of the majority ¾ who, they assumed, gained their livelihood in the private sector.

Denmark's and Sweden's problem has become the reverse. How shall a minority who derive their incomes from the private sector protect themselves against a publicly supported political bloc that not only represents a majority of the electorate but can also draw upon all the sources of power available to the state? And how is the publicly supported majority to guard against making decisions that may grant favors but may ruin the country?

The problem is particularly salient in welfare politics. Since a majority of the voters are employed by the public sector or dependent on its benefits, the incentives to reduce the public welfare system are weak. The majority have more incentive to use their ballots to raise their incomes and benefits without having to increase their work input.

Sweden's constitution sets no limit on the welfare mandate of elected officials. In the hands of the Social Democrats this mandate has produced a kind of doublespeak. On the one hand, there is a special concern for the many public employees and their services (egoism). On the other hand, the official motivation is to safeguard the health and prosperity of all the citizens (altruism). This prevarication provides both the fuel and the lubricant of the Swedish welfare doctrine.

Can our democracy survive the challenges of the maximalist welfare state? We would like to make such a question unnecessary by giving civil society and the market large enough roles in welfare so that the democratic political system can survive regardless of what happens to state-run social patronage.

Politics in Sweden for the most part means welfare politics. Whereas aggregate welfare expenditures made up 15.9 per cent of the national budget in 1920, in 1950 they were 39 per cent and in 1990 the share was 48.8 per cent (Kristersson 1994, p 16). In addition, there are less tangible indirect costs resulting from the risks and insurance which employers are obliged to cover, such as sick pay for the first weeks.

Sweden has turned moral responsibility for our neighbor's welfare into the responsibility [p353] of the taxpayer. Tax evasion has become synonymous with ignoring the needy along the wayside.

In 1900 the national government took one per cent of the citizens' incomes while the municipalities took four per cent, the same percentage for rich and poor. In 1902 the progressive income tax was introduced. The tax rate reached an extreme point around 1980 when the official expenditures were 20 per cent higher than in the rest of the OECD countries. In Sweden welfare fees (socialavgifter) are counted as taxes, more so than in the rest of the OECD, reasonably enough since the connection between fees and benefits is weaker here.

Public financing of social patronage has created an excess burden on the total economy. The large tax wedges distort prices, discourage investments, and make entrepreneurs abandon their projects. Du Rietz (1994) concludes his review of research findings:

| When state-run social patronage takes up a large part of the economy of a society, it is not infrequent for a state-run program to cost twice as much in the total economy as a corresponding privately run and financed program. |

(12)s193 |

In the opinion of Gunnar Du Rietz, one way to get around the disadvantages of costly public financing of social patronage is to privatize welfare programs and add more elements of ordinary insurance (including excess and deductibles) as well as to reduce benefit levels successively. He joins those who recommend citizen accounts in order to give households their own buffer in unforeseen events. Kjell-Olof Feldt (1994), economist and minister of finance under Palme and Carlsson, recommends another strategy, stating that "the welfare state cannot stay the same, equally comprehensive and generous, if we are going to pay for it out of our own incomes and not with loans from others." The Swedish welfare state should therefore be reduced to include only a core of "care, services, and education", thus abandoning support for housing, pensions and other schemes. Proposals by economists for reforms such as these have met with a cool reception. Instead of such structural reforms, general retrenchment has been the order of the day in the 1990s in order to put the finances of the Swedish welfare state in balance.

State-run social patronage is not innocent in the economic troubles of nations. In Sweden's case, however, one should add that inflationary wage settlements have an even greater share in the nation's economic woes. Moreover, through unemployment benefits, the economic problems inherent in the welfare state are joined to those produced by the labor market. There is a need to keep compensa-[p354] tion levels in most social insurance programs uniform; otherwise people tend to drift to programs with higher benefits (Bröms et al 1994). However, by linking unemployment insurance to problematic wage settlements, all the social programs designed as income protection wind up on too high a level. The excesses of wage formation in Sweden become then excesses of social insurance. This country has tied a tight knot between both its problem children: wage settlements and welfare costs.

In any tripartite form of cooperation between state, industry, and civil society, the market and civil society have an incentive to shift responsibility and costs onto the state, which has more easily available cash resources through its taxing power. This phenomenon occurs both in the case of social insurance plans and services in natura to the welfare populations.

| When social patronage is organized in such a way that the state is made partly responsible for financing and/or delivery, eventually its area of responsibility tends to turn into a public monopoly. |

(13)s211 |

This proposition casts a dire prognosis for subsidiarity as the organizing principle of social patronage. The Continental social states have traditionally financed and delivered welfare services through cooperation between the state, industry and the unions, churches and other institutions of local civil society. The trend has, however, continuously been in the direction of increased state involvement (Heinze & Olk 1981).

By definition, public insurance plans are state-run. However, the state does not have to manage them itself but can delegate the practical responsibilities to private interests, either on the market (e.g. insurance companies) or in civil society (e.g. nonprofit organizations). Such a provision was made, for example, in the paradigmatic Swedish Industrial Disabilities Act of 1916. This also gave employers a reason to monitor the costs of the system. Distrust of competition in social services was prevalent in Sweden in the 1920s and advances on the way to state monopolies were made in several areas, although these monopolies were only really take hold during the postwar governments (Berge 1995, 212-17).

There is, of course, the option for the state to compete with private insurance. We have one such case in Sweden in a scheme for voluntary public pensions dating from 1913. This was designed to be a premium reserve system. Throughout its long history, conditions for investors in this [p355] system have successively worsened. As a rule, governments are unsuitable at business since they play a double role: they make the rules and also play the game.

| When the state enters the market of commercial social patronage, it turns out to be an ineffective and unreliable competitor to private firms. |

(14)s217 |

In the market for social services, private actors such as insurance companies should not have to face a state competition that easily becomes unfair. However they should, of course, abide by a common set of rules laid down by law.

Regulated companies can be projected within health services. Health Maintenance Organizations (HMO) is the term used in the United States to denote a type of health insurance company that by contract or ownership organizes medical and hospital care, rehabilitation and the purchases of pharmaceuticals. These organizations represent the fastest growing form of health protection. A member in an HMO receives a list of participating doctors, health care centers, pharmacies, and hospitals. Doctors are not normally employed by the organization but are practitioners with temporary contracts. An HMO makes continual quality controls of its doctors and encourages the best referral system. The economic advantage of this is obvious: in the long run, repeated visits for the same complaint to a general practitioner will cost much more than a single visit to a competent specialist. Sweden's regional councils in charge of medical care (landsting) as well as försäkringskassor could be converted into competitive, privatized HMOs (Berggren et al. 1994).

As we pointed out earlier, the most common of the special welfare populations in modern market economies is that of the unemployed. The protection provided them by the state is, however, becoming antiquated. Companies shift their priorities from having a stable work force subject to continuous in-house training, to hiring temporary personnel of special competence only when they need them. This creates a labor market with an increasing number of self-employed and a decreasing number of employees with standard (union) contracts (Lyttkens 1996).

It is a great advantage for industry to have a mobile and diverse labor supply. The main responsibility for the unemployed should thus rest with industry, for reasons just as obvious as a government to take care of its war veterans or that a civil society be principally responsible for children and senior citizens. When industry accepts such a responsibility, its solution will be market-based.

Careers are more fragmented nowadays and more affected by unemployment than before. It is nowadays unreasonable to demand that an employer pay for all non-work periods; other arrangements are required for sabbatical leaves, study [p356] periods, and retirement, such as a citizen account. Different provisions must likewise apply to the long-term sick.

There is nevertheless room for what we would call Employment Maintenance Organizations, EMOs (in Swedish arbetsbevarande organisationer, AMO). They do not (yet) exist in real life. The concept is a new type of company that has elements of an insurance company, a union for unemployed, training center, and employment agency. The idea is for different EMOs to compete with one another, and an EMO's measure of success (and profit) would be its ability to get the jobless back to work. Everyone in the work force would by law belong to an EMO of his choice and pay a membership fee. Employers would pay a graded premium to the EMO for their employees or contractors depending on the degree of job security offered in the job contract.

Present-day labor market initiatives and unemployment benefit funds (a-kassor) could be privatized as competitive EMOs. Subject to government inspection, the market could thus take over much responsibility for the unemployed. Corporate law would, of course, have to be amended to provide for such entities as HBO and EMO companies.Civil Society

In civil society, compassion rules in the place of competition or organized justice. It is here that patterns of trust and cooperation are created for society as a whole, including the government and the market. It has long been commonplace knowledge that it is very expensive for the state to let law enforcement substitute for the training in civility and civic-mindedness that the civil society provides. Not even a police state has as many policemen as those policemen internalized in the population by a functioning civil society. It should be equally obvious that the active compassion and responsibility for the young, the sick, the elderly that is taught in civil society cannot be substituted by a social state. So many social functionaries are not to be found even in the most maximalistic welfare state.

Civil society's long-term effects on other parts of the larger society are nowadays a favorite topic for research and theorizing (Gidron, Kramer & Salamon 1992, Green 1993, Hall 1995, Nisbeth 1973, Putnam 1993, Seligman 1992, Wolfe 1989). In the social sciences in Sweden this research tradition has small but promising beginnings (Micheletti 1994, Sjöstrand 1995).

Two attitudes toward civil governments have evolved in Europe. One is that of the French Revolution which condemned and persecuted associations outside the state (Rose 1954). The second is that of England's "Glorious" Revolution which [p357] encouraged the voluntary associations of civil society at the expense of the state (Halévy 1949-52). Between the end of the 18th century and the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, England seems to have possessed Europe's most flourishing civil society. The state was small and the freedom of the citizens great. Politicians were pragmatic mediators, not ideologues. They had no blueprint for the modeling of society's families, economy, sciences, religion, art or morality. They performed their functions through selective measures in order to render somewhat more tolerable the spontaneous arrangements of civil society and business. Yet, judged by the standards of the time, a golden age was witnessed in the fields of politics, business, individual rights and freedom.

The traditions of freedom and the autonomy of civil society from the Glorious Revolution and the Scottish Enlightenment were transmitted to Great Britain's North American colonies later to become the United States. The tradition of a free and enterprising civil society came to Scandinavia in part directly from England, but mostly by way of returning emigrants from the United States (Thörnberg 1943).

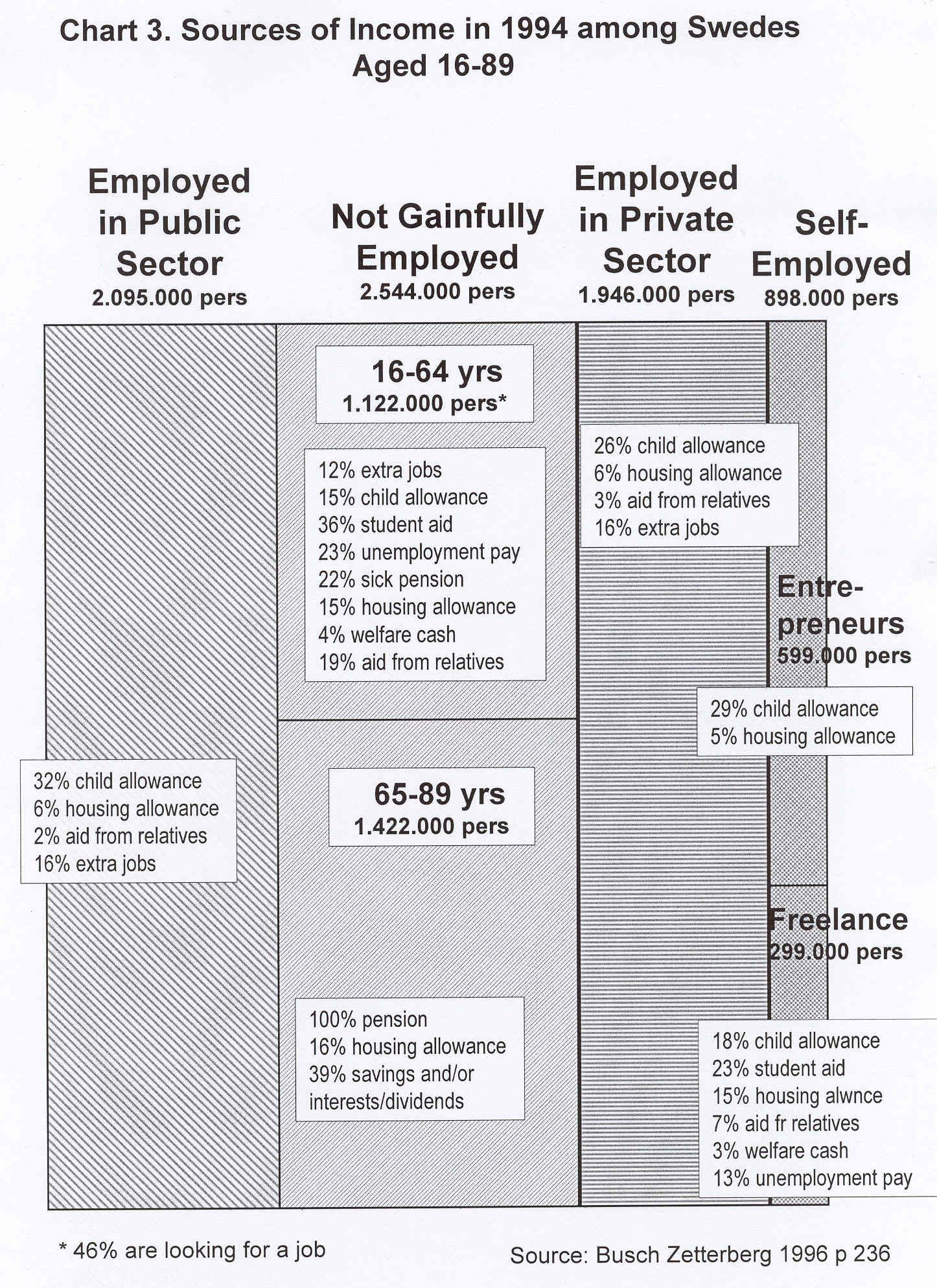

On the one hand, civil society consists of a "small world" of primary groups (Cooley 1909), such as family, playmates and youth groups, and, on the other hand, of a "large world" of secondary groups, such as churches, unions, founda-[p358]tions or, in other words, NGOs, i.e. large non-profit non-governmental organizations. The various connections of civil society to the state and the market are shown in Diagram 4.

The family is the most important of the primary groups. It was once common for many children to lose a parent due to death, but more children nowadays know the experience of having one parent leave home voluntarily. Although the number of divorced parents has risen in Sweden, still three out of four young people (73%) have not been exposed to either the divorce or death of parents. For the majority of young people, the contemporary image of a broken and dysfunctional family does not apply (Busch Zetterberg 1996, 17).

The second important primary group is the young person's circle of friends. Ljungberg (1996) found a great willingness among Swedish youth to get by on their own, particularly on the job market, despite the welfare safety net. Interest in state support may come when the young seek housing on their own and when they have their first child. Violence and/or drugs or crime are problems among about ten per cent of young Swedes, and the welfare state seems rather helpless in coping with them. Welfare dependency in the parental home correlates with significant social deviation of its children.

The most important secondary groups in Sweden are what are called folkrörelser or popular movements, free churches, temperance movement , labor unions, sports associations, et cetera. These turn out to be an essential element in democratic development. Popular movements originally had the role of carrying out important welfare functions on their own responsibility. As time went on, they have turned to extracting benefits and services for their members from the state. In a few instances they participate in the management of welfare programs, for example, in the funds for unemployment benefits (a-kassor) which are administered by the unions. However, when associations in civil society are called upon to administer state programs they tend to become more like public bureaucracies (Lewin 1992).

When civil associations manage state-financed social patronage, they loose their egalitarian, friendly stance and wind up becoming hierarchical and centrally regulated. (15)s266

This is a problem more for the Continental model of welfare than the Nordic one.

Civil society's voluntary and often cooperative approach to social policies, which was found also among the Swedish Social Democrats, was in the main abandoned in the 1950s in favor of all-governmental schemes.

[p359]

The market is one of the jaws of the pincers pressing down on modern civil society. When the market begins to overshadow civil society, it tends to splinter it. That is, purely individual preferences prevail over group loyalties.

The other jaw of the pincer is the government. Characteristic of the postwar social structure of welfare nations has been the state's interference in the welfare provided by civil society and commerce: it nationalizes a part of it and plants a crop of regulations over the rest. Nascent voluntary, cooperative, and commercial efforts to solve problems of social security and care were cut off. Once public systems were launched on the local level, they soon became normative, sometimes acquiring a de facto monopoly. In Sweden, their short-term advantages at a local level were obvious (Gustafsson 1988). They were consolidated into national systems and subjected to the common regulations of parliament. It would take many decades before the long-term accumulated disadvantages of the national systems were subjected to scrutiny.

The state's intrusion into civil society takes place both by nationalizing child care, education, health care and care for the elderly, and by covering it with a far-reaching regulatory system for rights and transfers. It is also in large measure a case of colonization, not nationalization. The presence of social legislation has had a fundamental effect on the decisions normally made within civil society but which now must be made in accordance with the rigid conditions of state-run insurance plans, benefits programs, and rules about job leaves (Lignell Du Rietz 1994).

In the beginning of the 20th century Max Weber expressed his disbelief in Marx’ prediction that the capitalist modernization would result in the dictatorship of the proletariat. Rather, he held, the future would be a dictatorship by the officials of the state bureaucracies. The outcome in the advanced welfare states is along Weber’s lines. It can now be further specified. In the name of welfare, legislators and social functionaries have established a kind of dictatorship rule over the proletariat (particularly the Lumpenproletariat). They have also established a colonial-type regime over the middle classes in which the latter the have freedom only within the rules set by their colonizers and their taxing power.

There are four different ideological proposals for the design of social patronage. Based on our own research, we reject the pure versions of all four current welfare ideologies: the Swedish welfare doctrine, the neo-liberal ideology, the communitarian ideology, and the approach of subsidiarity. [p360]

| Swedish welfare doctrine. Government schemes of social insurance and

state-run non-cash services of childcare, job placement, health care, social

aid and geriatric care replace reliance on relatives and charity as well as

on the market. We have seen the financial difficulties intrinsic to this concept. It is also difficult to implement. With the possible exception of medical care, it is not and has never been a realistic reflection of the Swedish welfare state. It has been a nostrum of politics, journalism, and social science. In practice a modern state cannot take care of its entire people from cradle to grave. | |

| Neo-liberal ideology seeks to make exclusive use of private insurance

arrangements and private welfare services. Social insurance should be

privatized as well as childcare, health care, job placement, geriatric care,

and other non-cash welfare services. This approach does not solve the problems of the poor who cannot afford to buy insurance policies or purchase services on the market. Special types of companies, such as HMOs and EMOs, could, however, be created which would give the market a larger role in the struggle against disease and unemployment than that which we have seen up to now. | |

| The communitarian ideology relies on civil society, both on primary

groups like the family and on secondary groups such as voluntary

associations with a social agenda. This approach can be encouraged by legislation, but it does not lend itself to legal enshrinement. It presupposes a tradition of self-reliance and responsibility. It may be an underused option but not an immediately available one. | |

| The ideology of subsidiarity; the first recourse of welfare populations

should be to civil society and the market, and when these have exhausted

their resources and can no longer help, the state should come in with

financing, and, in the last resource, take over full responsibility. This division of responsibility, which is central to the Continental social states, has apparently worked fairly well. However, it seems to be untenable in the long run. Once the state gets its foot in the door, the inner logic of democracy eventually causes it to go all in and take over responsibility for all social patronage. |

Today's many jobless are presented with a multitude of helping hands ranging from the state, the unions, customers in the informal sector, all the way to neighbors, friends and their own families (Berg et al. 1997). This diversity of assistance explains why the massive unemployment of the 1990s did not lead to massive starvation, evictions, or bankruptcies. What holds true for the jobless may now hold true for other welfare populations (children, elderly, sick and handicapped). The [p361] conclusion we draw from Sweden's crisis of the 1990s is a first specification of our Second Proposition:

| Welfare populations are best served by a diversified social patronage from state, market, and civil society. |

(16)s276 |

For an optimal division of responsibility in social patronage between the state, market and civil society, a pragmatic tripartite approach to welfare is called for. We must be aware of the fact that -

| One welfare population may obtain optimal results under a certain arrangement between the state, market and civil society, while another population is better off with a different spread of services. |

(17)s279 |

Ideologies of the one-size-fits-all variety should not be enlisted as far as social welfare is concerned. The best system for the young may not necessarily fit the elderly. The most appropriate plan for the sick and handicapped may not be the best for the unemployed. Market-based solutions may be the cheapest and most efficient in some areas but not in all. Civil society can offer many contributions, but it can not be all things to all men. The government is obviously suited for certain assignments but far from all of them. When policy analyses like our own can be deliberately freed from prevailing prejudices, they can offer a more balanced view and put popular assumptions into question.

The search for a well defined, reliable and optimal division of responsibility in social patronage between state, market and civil society can begin with a few simple considerations:

| For the young who cannot yet look after and support themselves, the primary groups of civil society should take on the principle commitments. State childcare benefits and subsidized childcare can supplement the contribution of the primary groups. | |

| For the short term sick, a market-based solution in the form of health maintenance organizations can be tested as a main alternative. | |

| For the long term sick, disabled or life-long handicapped of working age, the state's role will have to be much larger than that of the market, although government programs should not undermine the significant role played by civil society in for this group. | |

| For the unemployed, a market-based solution in the form of employment maintenance organizations can be tested as a main alternative. [p362] | |

| For the elderly who can no longer work or support themselves, income protection is needed in the form of pension insurance, state and/or private. |

The attraction of the Swedish doctrine of cradle-to-grave governmental welfare lay in its promise of a complete and reliable coverage. It also promised a life of equality. Our own proposal for a well-defined optimal tripartite cooperation in social patronage also entails complete and reliable coverage. Our proposal threatens neither democracy, nor state finances, in the way the current Swedish welfare doctrine has. It is a vision promising a life in dignity.

While new solutions are being tested, a whole family of ideas and concepts about the social state must be re-examined and true compassion must be put back into place after a long era of sentimental, utopian, and not very disinterested notions of welfare.

(1997)

On the Swedish scene there are no examples of a modern welfare program

that integrates the role of the state, the market, and the civil society. By

studying only Sweden we

could not illustrate what we had envisaged as the most viable welfare model.

However, in 1995 Germany introduced an old age insurance that approximates

our ideals. After ten years of operation in a tough economic climate it serves

well as a real-life

demonstration of the combined efforts of the state, the civil

society, and the marketplace to meet the demands of a growing group in the

population.

The insurance becomes due when a person needs care for a minimum of one and

a half hours per day. Relatives and other caregivers are paid for their

services and receive four weeks' vacation. The elderly can chose the home

care services they want within the framework and fees of the insurance

system. The insurance pays for wheelchairs, special beds, and other aids to

daily living. The three types of service for the elderly -- home care,

service residences, and nursing homes/hospices -- are available on three

levels. The form and level that the insurance plan entitles one to is

determined by a physician, not by local politicians or civil servants. Even

if they have different care needs, married couples are kept together as far

as possible. The form of service granted can be upgraded by the recipient.

For example, a person who has been granted home care can move to a service

residence by paying the difference out of his own pocket.

In 2004 two million Germans availed themselves of old-age insurance. More

than anything else, the qualification that a person requires care a minimum

of an our and a half daily affects the extent to which the insurance is can

be utilized and make it affordable for the sorely pressed official

treasuries.

Germany's capacious social insurances are partly financed through the

federal and constituent states, but it is not implements by them.

Approximately 85 percent of Germans have placed their sick insurance in the

public system (Gesetzliche Krankenkasse or GFV). Others carry private

insurance. The efficiency of the system benefits from the competition that

exists between insurance companies that vie to deliver GFV's sick care. They

are known by their three-letter abbreviation: AOK, BEK, BKK, DAK, KKH, TKK,

among others.

The German old-age insurance described above is automatic for all members in

the public system, GKV, and is obligatory for all others. The cost is 1.7

percent of wages/salaries (split evenly between employer and employee), and

1.7 percent of the pensioner's income. The above mentioned insurance

companies either buy the practical implementation of the policies or handle

it themselves. Unlike the Swedish arrangement whereby counties and

municipalities implement the insurance plans, in the German welfare state,

voluntary association, churches and unions have traditionally carried out the

practical aspects of the plan. They can provide home care and service

residences as well as out-patient treatment and some hospital care. In

Germany there are rules governing the division of responsibility in the

public sphere between the state, industry and business, and the civil

society. All is not relegated to either the market, the state, or the civil

society.

Another difference between Germany and the Nordic countries in respect to

their welfare systems is the German voter's tendency to associate German

welfare policies primarily with the conservative Christian Democrats,

whereas Scandinavian welfare policies as mainly viewed as a project of the

Social Democrats.

(2005)

Andreen, P G & Boalt, G (1987), Bagge får tacka Rockefeller. Rapport i socialt arbete, nr 30, Stockholm: Socialhögskolan.

Anttonen, A (1990), "The feminization of the Scandinavian welfare state", L Simonen (red), Finnish debates on women's studies. Tammerfors: University of Tampere.

*Arvidsson, H, Berntson, L & Dencik, L (1994), Modernisering och välfärd: om stat, individ och civilt samhälle i Sverige. Stockholm: City University Press.

Berg, J O et al (1997), Den dolda världen. Stockholm: City University Press. In press.

Berge, A (1995), Medborgarrätt och egenansvar: de sociala försäkringarna i Sverige 1901-1935. Lund: Arkiv.

Berggren, G R m fl (1994), HSF-modellen. Stockholm: Stiftelsen MOU. (Medborgarnas offentliga utredningar. 1994:1).

*Borg, A (1992), Generell välfärdspolitik: bara magiska ord? Stockholm: City University Press.

*Bratt, P (1996), "Samhälls- och människosyn i social- och strafflagstiftningen", preliminärt manuskript till forskningsprogrammet Den svenska Socialstaten, City universitetet, Stockholm.

Bröms, J et al (1994), En social försäkring. Rapport till expertgruppen för studier i offentlig ekonomi. Ds 1994:81. Stockholm: Finansdepartementet.

*Busch Zetterberg, K (1996), Det civila samhället i socialstaten: inkomstkällor, privata transfereringar, omsorgsvård. Stockholm: City University Press.

*Carlsson, S. (1995),. Socialtjänstens kompetens och funktion. Stockholm: City University Press.

Coase, R H (1937), "The nature of the firm", Economica, nr 4, sid 386-405.

--(1960), "The problem of social costs", Journal of Law and Economics, nr 3, sid 1-44.

Cooley, Ch H (1909), Social Organization. New York: Scribners.

[p363]

*Du Rietz, G (1994), Välfärdsstatens finansiering. Stockholm: City University Press.

Edebalk, P G (1993), "1916 års olycksfallsförsäkring: en framtidsinriktad socialpolitik", Scandia, vol 59, sid 113-134.

Elmér, Å (1960), Folkpensioneringen i Sverige med särskild hänsyn till ålderspensioneringen. Lund: Gleerup.

Esping-Andersen, G (1990), The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Feldt, K-O (1994), Rädda välfärdsstaten! Stockholm:Norstedts.

Flora, P & Alber, J (1981), "Democratization, and the development of welfare states in Western Europe", Flora, P & Heidenheimer, A J, red, The development of welfare states in Europe and America. New Brunswick: Transaction Books.

*Frankel, G (1991), "Välfärdsstatens frontpersonal: en kvalitativ undersökning", rapport från Demoskop AB till City-universitetet, Stockholm.

Fölster, S (1994), "Socialförsäkring genom medborgarkonto: vilka är argumenten?" i Ekonomisk Debatt, vol 22, nr 4. 1994.

Gidron, B, Kramer, R M & Salamon, L M editors (1992), Government and the third sector. Emerging relationships in Welfare States. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Green, D G (1993), Reinventing civil society. The rediscovery of welfare without politics. London: IEA Health and Welfare Unit.

Gustafsson, B (1988), Den tysta revolutionen. Uppsala: Gidlunds.

*Gür, Th (1996), Staten och nykomlingarna. Stockholm: City University Press.

Halévy, E (1949-52), A history of the English people in the nineteenth century, 6 vol., London: Benn.

Hall, J A, red (1995), Civil society. theory, history, comparison. Cambridge (UK): Polity Press.

Heinze, R G & Olk, T (1981), "Die Wohlfahrtsverbände im System sozialer Dienstleistungsproduktion: Zur Entstehung und Struktur der bundesrepublikanischen Verbändewohlfart", Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologi und Sozialpsychologie, no 1.

Hicks, A, Misra, J & Nab Ng, T (1995), "The programatic emergence of the social security state", American Sociological Review, vol 60, June, sid 329-349.

Kangas, O (1991), The politics of social rights. Stockholm: Institutet för social forskning. (Dissertation series nr 19).

Korpi, W (1983), The democratic class struggle. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

-- & Palme, J (1993), Socialpolitik, kris och reformer: Sverige i internationell belysning. Bilaga 17 in Ekonomikommissionen (A Lindbeck et al.), SOU 1993:16, Nya villkor för ekonomi och politik. Stockholm: Allmänna förlaget.

*Kristersson, U (1994), Det socialpolitiska arvet. Stockholm: City University Press.

Langby, E (1984), Vinter i välfärdslandet. Stockholm: Askelin & Hägglund.

Lewin, L (1992), Samhället och de organiserade intressena. Stockholm: Norstedts.

*Lignell Du Rietz, A (1994), Myten om jämställdhet i välfärdsstaten. Stockholm: City University Press.

[p364]

Lindbeck, A (1993), The welfare state. The selected essays of Assar Lindbeck, vol 2. Hants: Edward Elgar.

Linz, J J & Stepan, A (1996), Problems of democratic transition and consolidation. Southern Europe, South America, and post-communist Europe. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Lipsky, M (1980), Street-level bureaucracy: dilemmas of the individual in public service. New York: Russell Sage.

*Ljungberg, C J (1996), Ungdomar i socialstaten. Stockholm: City University Press.

Lyttkens, L (1996), Alltmera huvud, allt mindre händer. Stockholm: Akademeja.

Micheletti, M (1994), Det civila samhället och staten: medborgarsammanslutningarnas roll i svensk politik. Stockholm: Fritzes.

Nisbet, R A (1973), The quest for community. London: Oxford University Press.

*Nowacka, E (1991), En bur sökte sin fågel: berättelsen om Ewa och Kasia. Kommentarer Bo Edvardson & Agneta Pleijel. Stockholm: Timbro.

Pareto, V (1991), The rise and fall of elites. An application of theoretical sociology. New Brunnsvick, NJ: Transaction Publisher.

Putnam, R D (1993), Making democracy work. Civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

*Rivère, H (1993), Meningen var ju att hjälpa människorna, inte att ta ifrån dem ansvaret. Stockholm: City University Press.

Rose, A M (1954), "Voluntary Associations in France" in his Theory and Method in the Social Sciences. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 72-115.

Salonen, T (1993), Margins of welfare. Hällestad: Hällestad Press.

Seligman, A B (1992), The idea of civil society. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Sjöstrand, S-E (1995), "I samspel med andra. Om organisering av ideell verksamhet" E Amnå (red), Medmänsklighet att hyra? Örebro: Libris.

Skocpol, T (1992), Protecting soldiers and mothers: the political origins of social policy in the United States. Cambridge, MA: Belknap.

Stephens, J D, Huber, E & Ray, L (1995), "The Welfare State in Hard Times", Conference on Politics and Political Economy of Contemporary Capitalism, Chapel Hill, NC, 9-11 september 1994 to be published in Kitschelt, H, Lange, P, Marks G, & Stephens J D (eds.), Continuity and change in contemporary capitalism, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, forthcoming.

Svallfors, S (1992), Den stabila välfärdsopionionen. Umeå: Sociologiska institutionen vid Umeå universitet.

Therborn, G (1989), "Arbetarrörelsen och välfärdsstaten", Arkiv för studier i arbetarrörelsens historia, nr 41-42, sid 3-51.

Tulloch, G (1989), The economics of special privilege and rent seeking. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publisher.

Thörnberg, E H (1943), Folkrörelser och samhällsliv i Sverige. Stockholm: Bonniers.

Turner, F J red (1995) Differential diagnosis and treatment in social work, 4th ed. New York: Free Press.

*Uddhammar, E (1997), Arbete, välfärd, bidrag. En dynamisk analys av folkets välstånd och välfärdsforskningens missförstånd. Stockholm: City University Press. In press.

Wolfe, A (1989), Whose keeper? Social science and moral obligation. Berkeley: Univerity of California press.