![]()

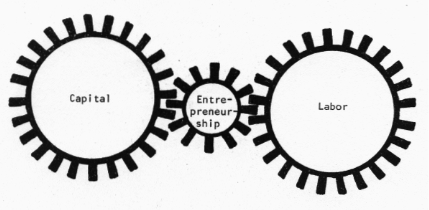

Both liberal and marxist economists tend to ignore the entrepreneur and innovator and speak of capital and labor as “the only two major elements in production”, as did Mr. A. M. Krusro in 1977 at the Amsterdam Conference of the International Chamber of Commerce. But Dr. G. Tacke quickly joined the discussion on that occasion and added the entrepreneur as “an indispensable factor of production independent of, and between labor and capital, with its own profile and structure”.

The spirit of entrepreneurship brings labor and capital together in the productive enterprise. It is a catalyst without which both labor and capital would be idle.

The spirit of entrepreneurship is easy to recognize when we see it, but it is difficult to define formally. We might see it as a dynamic integration of four elements:

Each element may be well known by itself, but their integration is a less process.(1) the development of marketable innovations,

(2) the charisma to attract capital for their exploration,(3) the leadership to organize labor and technology for their production, and

(4) the marketing skills to distribute and sell them.

Systematized knowledge about entrepreneurship is incomplete. Harvard University, inspired by the great Joseph Schumpeter, did create a research program in entrepreneurial history, and its first monograph appeared in 1931. But research in entrepreneurship has not spread through the community of social scientists. The topic has not been amenable to the mathematics of the economists. We lack the data banks, the specialized professorships, the graduate courses, the fellowships, the research grants, the journals, the conferences; in short, we lack the scholarly tools that makes possible a massive and continuous research effort into entrepreneurship. So it is that the most pivotal phenomenon of our civilization is subject to many guesses and intuitive hypotheses but few systematized facts and few, if any, established theorems.

A spirit of entrepreneurship can develop in many contexts. But so far capitalism has been its most hospitable framework. We do not deny the advances of the communist countries and the success of socialist leaders in raising the standard of living and allocating new material wealth according to criteria of social justice. But it is nevertheless a striking fact of our times that state-run economies of the Soviet type have failed to develop a spirit of entrepreneurship and a climate of innovation that can match those of the capitalist countries.Given our state of knowledge it is easier to talk about the entrepreneur than about entrepreneurship. We can readily grasp the former, when the elements of entrepreneurship combine in one person who himself is the idea-man, inventor, or designer and who himself puts up the capital from his own pocket, supervises production and does the selling. The local production of bygone times of the necessities of shelter, clothing, and food was often in the hands of entrepreneurial families who ran small-scale industries for building materials, textiles, and foodstuffs. However, entrepreneurship in contemporary advanced societies is of an entirely different order. The elements of entrepreneurship must now combine in an organization whose various functions may house many product ideas, hundreds or thousands of employees, numerous technologies, a sales network that may span many parts of the globe, and capitalization counted in millions of dollars.

The public’s many encounters with personal entrepreneurship have contributed to the common confusion that the capitalist and the entrepreneur are one and the same, or at best, different sides of the same coin. And many who know better and do make a distinction between the two consider the difference unimportant. For example, Karl Marx and his followers maintain that entrepreneurs without capital of their own are in the grip of capital, being kept men. Such may indeed have been a dominant pattern in the first or second generation of capitalism. A realistic look at the relationship in today’s affluent societies would reveal something entirely different: now entrepreneurs try to engage the services of capitalists more often than capitalists engage the services of the entrepreneurs.

Organizational entrepreneurship on a large scale is a characteristic of today’s advanced societies. Such entrepreneurship has many advantages over the personal variety that has dominated in the past and still is growing in many less developed countries. Organizational entrepreneurship can span generations without the threats to continuity posed by the whims of inheritance in selecting successors. It can handle a larger number of marketable innovations at the same time, making sure that new ones enter the market as old ones become obsolete. It is not barred from production requiring high initial investments. It can handle long and complex productions and is not overly dependent on quick sales. It can afford and encourage the training and specialization of its employees. The chemical, metallurgical, pharmaceutical, automotive, aerospace and other heavy modern industries are and must be organizational entrepreneur- ships. The old-fashioned personal entrepreneurships have declined in number in the advanced countries, but they are far from extinct. The recent technologies of the microprocessor and biotechnics will probably be very hospitable to the small entrepreneur.

A high tribute is paid by big business to small business. Big business is and should be deadly afraid of growing stale and bureaucratic. Big business is anxious to preserve the entrepreneurial morality inherited from the personal entrepreneurships. Thus successful big business tends to organize itself as federations of smaller, more personal entrepreneurships.

Entrepreneurial morality is more positive than negative: it is more concerned with the obligations of the entrepreneur than with prohibitions. The entrepreneur is to act, not to abstain. He is to exert himself at all times and make the most of his opportunities, indeed often to create them. Many will come afterwards and comment on the entrepreneurial deed: “Oh, I could have done that, too”. But the point is precisely that they did not do it. The entrepreneur, however, caught the opportunity and acted upon it with a creative response.

The entrepreneurial spirit frets at the limitations imposed on human effort and strives to break through them by some prodigious assertion or cunning achievement or by some clever application of technology, all done with a keen sense of timing.

The entrepreneur enjoys business risks as long as there is a reasonable chance of gain. He delights in escaping from deadly office routines into the more exciting marketplace. He enjoys the finished deal as a great glory, but accepts being outbid in a deal - even if the glory is less.

The entrepreneur is not a hypocrite: he admits openly that the sweetness of life requires a certain amount of personal wealth. However, wealth is not usually sought for itself by an entrepreneur but serves two of his more prominent needs. The typical entrepreneur has a strong need to achieve. Personal wealth is one of his ways to keep score on achievement. He has also a strong need for independence, to be his own master and to control his own destiny. Personal wealth is a fundamental resource in this striving.

The entrepreneur is proud of his firm and his family, and in exerting himself for them he obeys something deep in his nature. He competes fiercely with other firms and families. But at the same time he honors anyone who can meet a payroll and close a profitable, useful deal. No competition, however merciless, need result in an insoluble conflict that ends in the destruction of a fellow entrepreneur. The entrepreneurial spirit has no room for the total vengeance of a vendetta. For no defeat of an entrepreneur is definite. He usually comes back with amazing resilience, in the same field or in another.

The nobility of the entrepreneurial outlook lies in the prominence it gives to personal sacrifice for a chosen cause. It is often said that the entrepreneur is selfish, lives for himself. This is hardly fair. He lives for a cause, innovations which he wants to promote across communities, nations, and worldwide marketplaces.

Unlike the capitalist and the laborer, the typical entrepreneur is exceptionally loyal to his enterprise. The capitalist will switch his money to a safer and more profitable company if his investment is threatened. In a publicly held company he will simply sell his shares without even telling management why he distrusts the future of the company. The laborer, clerk, salesman, or other employees without entrepreneurial duties or commitments may also switch jobs to other companies if wages, benefits, or working conditions seem more attractive there. The entrepreneur, however, will stick with his firm through adversity. He has tied his enterprise to his ego and can only abandon it with agony under unusual and special circumstances.

After this exposition of entrepreneurial virtue you may ask if there is no vice among entrepreneurs. The answer, of course, is yes. Entrepreneurial morality has been criticized - as has communist morality - for ignoring spiritual achievements. It is too concerned with calculation and too little with contemplation. Entrepreneurs call many parts of the world underdeveloped, and they are right in material terms. But the civilizations of the Third World call our parts of the world underdeveloped in emotional, spiritual, and religious terms. Entrepreneurial morality has also been criticized - as have other moralities that stress a heroic attitude toward life - for a failure to set limits and a built-in lack of balance. It believes in boundless expansion: all trees can and should grow to reach heaven. It is not coincidence that much criticism of entrepreneurship today is leveled in terms of limits and balances - the limits of growth and the ecological balance.

The dilemma is a familiar one in the context of Western history. Socrates lived in a heroic age in which the spirit of entrepreneurship flourished and in which courage in battle and success in warfare were even more honored than commercial or artistic successes. He grew concerned over

the excesses encouraged by the heroic morality. Plato tells how Socrates, after a dialogue with

Phaedrus, passes a temple of Pan and offers a

prayer:

“0h beloved Pan and all the other Gods of this place,Do we need any more Phaedrus? For me that prayer is enough.”

grant to me that I be made beautiful in my soul within,

and that all external possessions be in harmony with my inner man.

May I consider the wise man rich;

and may I have such wealth as only the self-restrained man can bear or endure.

Plato carried the criticism of the Athenian heroic-entrepreneurial spirit beyond prayers for a balanced personality. In Georgias he complains: “They have filled the city with harbors and dockyards and walls and tributes instead of with righteousness and temperance”. He ‘denied most achievements of the Golden Age of his society and set out to plan a society that would prevent a repetition of such achievements by free, responsible men of heroic, entrepreneurial actions.

Today many intellectuals deny the values of the Industrial Age and want to place the entrepreneurs under guardianship. An increasingly limited tolerance of grandeur marks also our

times.

The serious slowdown in economic expansion in the 1970s has, of course, many and complex causes. On balance, there is no lack of capital and certainly no shortage of manpower. There seems, however, to be a short supply of profitable investments in the affluent societies. The reason for this may vary from country to country. But one common reason is the lack of marketable innovations.

It is often heard that innovations occur mostly in small firms and rarely in large ones. In support of this theses statistics are quoted showing that over half of the patented innovations emanate from small firms. Thus one tends to look for the climate of innovation in the small shops. This, however, is misleading. For every large business there are a thousand small enterprises, and most of them are not very innovative.

The appearance of marketable innovations within the large business establishments in an affluent society is not a matter of chance, nor is it dependent on a flash of genius. It is the result of a much more orderly, more pedestrian process. A most remarkable achievement of the modern entrepreneur is the

creation of organizations in which the development of innovations is routine. The main bench marks in the process of developing marketable innovations are well

known:

(1) Long-range planning enables a corporation to gauge the need for new products and markets and spreads an awareness of this through the ranks of the corporation.Corporations adopting these procedures retain their old concern for volume and quality of production while adding a new concern for novelty and change.(2) There is a separate budgeting of time, money, and man-hours for innovations inside the firm and for the procurement of marketable ideas from outside.

(3) An established routine provides for impartial evaluation of innovative concepts and for the setting of priorities among them according to how well they suit the firm’s marketing and level of technology as well as their estimated impact on the market.

(4) Test production and trial marketing are managed by a special organizational unit.

Experience shows that these two fields of endeavor need to be demarcated. The research and development budget must be separate from the production budget. The developers should not be personnel borrowed from production and liable to be recalled to their old jobs to handle crises there. Management of production should be separate from management of research and development, for no day-to-day production manager can be expected to have the time or motivation to develop innovations that would render obsolete the very process he is managing. Du Pont’s development of nylon, Bell Telephone’s development of the transistor, the bubble memory, and the laser, Battelle’s development of the xerographic process were all done in separate laboratories; in the case of xerography Battelle in fact was an outside laboratory commissioned to do the work. We can also derive an important lesson from the fact that management backed these inventions not because they were technological miracles - the world is full of technological miracles - but because management believed that these inventions would have a tremendous impact on the market.

In innovation-prone corporations top management should ideally act like the controller in an airport tower and usher in one innovation after another in an orderly fashion. This is the ideal. Reality is too often a far cry from this ideal. Corporations tend to grow complacent about innovations in good times when the established products sell well. When their sales drop and distress signals are heard there is a sure shortage of both time and money for the development of new products and markets.

Top management, of course, should be required to take a special interest in the development of marketable innovations. Innovations should be a standing item on the agenda for board meetings. It is counterproductive to reward top management only on the basis of the results in the next Annual Report. The development and marketing of innovations requires a longer-range perspective than that afforded by the accountant’s annual statements.

In advanced countries, then, marketable innovations do not simply happen: they are managed. This does not mean that we rule out the individual tinker of the independent inventor. But judging from patent applications, an increasing share of inventions nowadays emerge under a corporate umbrella as part of the research and development effort. Independent inventors are declining in number in affluent countries, and are not as important as one would expect from the attention they receive from journalists. In the United States a new profession of “invention brokers” has recently come into being. They assist independent inventors and companies that have innovations which they themselves do not want to exploit.

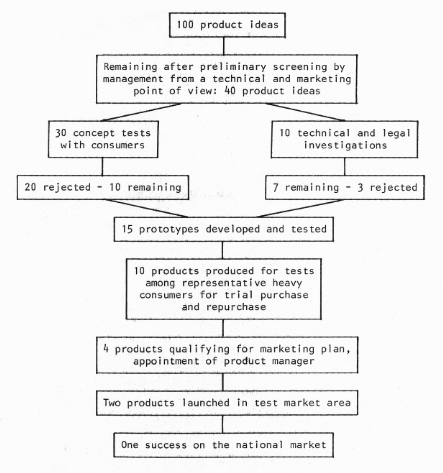

There are no general statistics available on the rate of failure in the innovative process. The diagram below has been used by consultants in Finland and Sweden to introduce management to the expected ratio between success and failure in launching new products for the household market.

Like other types of investments, the return on R&D is marred by increasing uncertainty in times of inflation and currency instability. In the late 1970s, we can see that government spending on research and development in the OECD countries is not increasing; in the United States it is actually declining. Money spent on corporate research remains at a figure that is less than 2 per cent of sales.

Government-sponsored inquiries into the worsening climate of innovation are under way in the United States, Great Britain, Sweden, and other countries. As these studies report, we are likely to hear in more or less polite paraphrase that government itself is at fault. By design or accident, governments are strangling the spirit of innovation in a web of bureaucracy, regulation, and taxation. To get new products or services into use is nowadays often as much a task for lawyers as for innovators. We live in the aftermath of the environmentalist and consumerism movements. And the aftermath has afforded us not only a better environment and safer products honestly presented. It has also introduced an incredible web of regulations, some of which are contradictory and some of which are obsolete products of bygone, unrealistic, and occasionally invalid public concerns. The political system clearly needs better devices to get regulations off the books, more systematic efforts to simplify the law, and better routines to get new legislation into harmony with existing laws.

In the conflict between innovators and regulators the role of the mass media cannot be ignored. It seems the media not only focus more on the conceivable harm an innovation can cause than on its obvious benefits. The media usually present the encounter between innovator and regulator as fight between the big guys and small guys, as a class struggle in which the interests of capitalists are pitched against the interests of the masses. Regardless of the outcome, the entrepreneurs and innovators usually walk away feeling dishonored in the media. A more realistic perspective is to see the struggle as one between two vested interests and two styles of life, the bureaucratic and the entrepreneurial, not as a class conflict.

However, the business community cannot put the entire blame for the worsening of the climate of invention on governments and other external forces. Some of the problems are home-made.

We select and promote more readily to captains of industry those who are skilled in handling manpower, capital, and marketing than those who are skilled in handling knowledge arid inventions. The number of civil engineers in top positions in the listed companies of the world is. steadily declining. Also in the parliaments of the world the engineer is very rare; there are actually countries entirely dependent on advanced technology without a single civil engineer in their parliament. What will become of the greatest technological civilization known to history when it stops admitting engineers to the decision process? No country today has engineers in corporate or political office to an extent that is commensurate with the importance of technology for national destiny.

We have also had some obvious difficulties in harboring the innovators in the corporate structure. The innovator needs periods of isolation from the day-to-day business process; he must be allowed periods of apparent inactivity; he needs freedom of thought and the stimuli of unorthodox approaches; he must be permitted a dual loyalty: to his firm and employer, and to an invisible college of fellow scientists-inventors- technicians. The innovator needs encouragement: generous treatment from the payroll office and the tax man. Innovators thrive where exceptional achievements can bring exceptional

rewards.

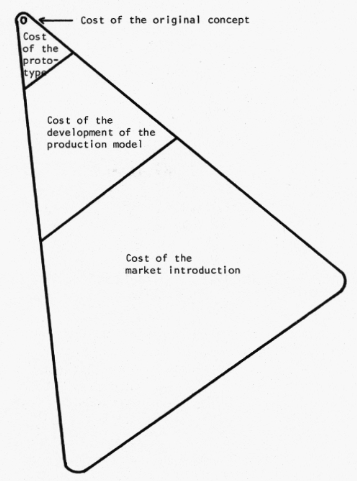

Most independent inventors are squeezed out of the picture by the increasingly heavy costs and the management skills required as an innovation goes through this process. There are, of course, outstanding exceptions to this: the name of Edwin H Land of Polaroid comes to mind. But to survive with an innovation that has such a growing appetite for capital the inventor needs the services of realistic venture capitalists. In Sweden the government has a program to assist inventors along the expensive road between prototype and production model. It is too early to tell whether this measure will keep the small cadre of independent inventors alive. Additional and larger assistance is needed on the still more expensive road between production model and marketing.

When innovations for households and industry are explored under a corporate umbrella the problem of capital is not normally a serious one. In interviews with persons responsible for product development in Swedish industry we found that “lack of capital” ranked twenty-first in importance and frequency among the problems mentioned. Twenty problem areas were considered worse than that of shortage of capital.

The most serious obstacle to product development as revealed in this study is a lack of protection of the development work from intrusions from production and administration. The innovators in most corporations are apparently not allowed to use their time for innovation! The second most serious problem area is a lack of knowledge of what the market will buy and use. There is a failure to use contacts and proper research to ascertain the needs of the market. The innovators need to come closer to the future users of their innovations, to learn about their problems and about their complaints with existing products and services.

Capital and management requirements to fight obsolesce in the affluent countries are of serious scope today, so serious that the banking systems and capital markets in most countries have government help to cope with it. When a government - or a group of governments such as the EEC - is faced with the problem of large-scale obsolesce in a basic industry it can respond in two ways: (1) It can give in to the crisis and the accompanying political pressures by providing protection and subsidies, including the biggest subsidy of all, nationalization; or (2) it can take a longer-range view by providing rewards through a series of incentives and/or resources, generally on terms which are themselves incentives.

We have in the recent decade gone a long way on the subsidy route. Several affluent countries now spend more on subsidies to distressed industries than they spend on research and development. But few will argue that we now have a healthier structure, say, in steel or shipbuilding than we had prior to large—scale subsidization. Of course, a government must be allowed to give temporary aid to industries in temporary trouble. But lasting subsidies, particularly those to export industries, are a threat to worldwide economic well—being; they become prolonged protection of inefficiency and obsolesce.

The boom in world trade in the 1960s was ushered in to the tune of the Kennedy round of mutual tariff reductions. The boom of the 1980s could be accompanied by a Carter round of negotiations on mutual reductions in subsidies. These talks might also include the special kind of subsidies to manufacturing provided by the so-called Free Trade Zones in the Third World. For a healthy development of the world economy and of a world trade with decent prices is threatened today both by the rich welfare states that rescue jobs in obsolete export industries by subsidies and by poorer states that serve international companies with cheap labor without charging the normal costs for pensions, health benefits, and environmental protection.

How can the affluent societies work out alternatives to government subsidies to obsolescent industry? We have set up in recent decades many institutions to serve the capital needs of the less developed countries. We have the World Bank, the United Nations Development Program, the Interamerican Development Bank, the African Development Bank, the Asian Development Bank, and the Central American Bank for Economic Integration. But in the affluent countries we do not have an International Bank for Reconstruction.

The existing banks for developing countries were initially financed by government contributions, but they are gradually beginning to float bond issues and attract funds from the private money market. An international bank for reconstruction of obsolete industry in affluent countries could, from the beginning, obtain the lion’s share of its capitalization from non-government sources.

Until recently the banks designed for the developing world concentrated heavily on government projects, mainly of an infrastructure character. Recently, however, there has been more emphasis on getting closer to the people. For example, the World Bank has shifted priorities to agriculture (small farmers), education, nutrition, and community development. As a result there is greater emphasis on creating local instrumentalities to disburse funds to small farmers and small communities through cooperatives and local banks, especially agricultural banks. The World Bank has also created a quite active subsidiary organization, namely the International Finance Association, which has the responsibilities of encouraging the creation of privately controlled industrial and business banks, in Latin America called Financerias. The Association has also taken equity capital in such banks.

Organizational inventiveness in this effort in the less developed countries is impressive. We can learn much from it when setting up instrumentalities to deal with obsolesce in the basic industries of the developed countries.

Take a leaf from the book of experience in international finance in the less developed world and add a thorough knowledge of the innovative process and you can see the contours of a bank for reconstruction of obsolete industries in the developed world. Such a bank could identify needed innovations that are transferable between countries, provide capital for the introduction of innovation and for the modernization of plant and equipment, and provide capital for the needed investments in selling and marketing. It would be an institution set up that it would earn a profit, could pay interest on its bonds, and be financially self- sufficient. Through its services it would preserve a worldwide market economy, not hamper it as do subsidies to export industries from national governments.The history of the Northern Hemisphere from the time of the French and American revolutions is very much a history of the movement from status to contract. It was this movement that opened the gates for an entrepreneurship which no longer became dependent on royal privilege and permission. When the modern entrepreneur organizes production and approaches the market he enters into freely negotiated contracts with employees, suppliers, buyers, and shareholders. The right to contract is as essential to him as the air he breathes.

At present the right to contract is no longer expanding, except, perhaps, for women. The remnants of the status society in terms of sex roles have been the last to go. It is interesting to note that at a time when this last area moves from status to contract, many other areas have moved from old-type contracts to new forms.

A most important modification of contract in affluent societies has given voluntary associations the right to enter into agreements that are binding upon their members. The individual laborer and the individual employer have to abide by the contract made between the labor union and a federation of firms. Thus, some effective right to contract and to control one’s own destiny has been taken from the individual and become vested in his organizations. Parallel trends, although less formal and codified, can be ascertained for farm groups, consumers’ cooperatives, and other voluntary organizations. These groups also make enforceable contracts on behalf of their members. Sometimes the other party to the contract is an employer, sometimes it is the state itself, acting as cosponsor of a welfare program.

An old-fashioned contract was achieved by shopping around for the best deal and by competitive bidding. Contracts made by large, powerful organizations acting on behalf of their members in collective bargaining cannot be of this nature. A situation in which the winner takes all and the loser gets nothing is impossible. Rewards reaped from organization contracts tend to be modest gains, and to be fairly equally distributed among all members, regardless of the merit and effort of the individual. This has proved discouraging to the innovators and entrepreneurs, who thrive on the prospect of truly big rewards.

The impact of organizations equipped with these rights to collective contracts is considerable. To a very great extent a person’s political influence and financial circumstances in today’s affluent societies in Europe depend on what associations he belongs to. This new pattern, however, is not quite the same as the feudal one when a man’s status as nobleman, farmer, or burgher determined his entire life. The movement from status to contract has not been reversed. Although strong forces make for collective and compulsory joining of the large organizations, the citizen is still free to leave them, something not true of the feudal estates.

The main effect of unionization has been felt by the capitalists, not the entrepreneurs. Unions have tilted the balance of power between capital and labor in favor of labor. Taking an average year the 1970s in the affluent societies we find that the ratio of what labor receives from the listed corporations to what capital gets is about 100 dollars to 4 dollars. And to get the figure 4 dollars for the capitalists we have to add both dividends and retained earnings. If enacted, the Dutch proposals of Vermogenaanwasdelning and the Swedish proposals of löntagarfond will tilt this balance further toward labor.

A major consequence of the welfare state has been to preserve the individual’s ambitions and motivation at times when adversity strikes.

Since the state steps in with a helping hand in crises - whether they are related to the individual’s work situation, family, or health - he is not easily pushed into a despair or fatalism. Contrary to conservative ideology, there is much individual competition and ambition to achieve and get ahead in the welfare states.

The change is this: competitors do not have to face the roughest consequences of their losses. A system has evolved in the advanced welfare states according to which one can still make both small and big gains, but one can make only small losses. The Swedish pension reform enacted in the late 1950s is indicative of the principles of the welfare state: each citizen is guaranteed an annual old age pension amounting to some 60 per cent of his average earnings during the ten best paid years of his employment. In the same way health benefits are tied to earnings. Motivation is high, then, to improve earnings. By retiring from the labor market a Swede may lose some income, to be sure, but never more than 40 per cent of what he earned in his best years. A floor of another kind is represented by the large number of positions, both in government and industry, that have tenure contracts. In these positions one’s job is secure but promotion is dependent upon performance. Both these examples indicate a curious mixture of status and contract: a man’s status is insured as in a feudal society, but he can compete for better contracts as in the developed society. This kind of “insured contract” is very characteristic of the affluent welfare state.

A society based on insured contracts is not of itself hostile to entrepreneurship and its ambitions and rewards. The welfare politicians who set up the insured contracts do a job that is important and necessary and for which the entrepreneurs usually lack both skill and inclination. The welfare politicians redistribute the enormous wealth generated by enterprise so that life in all segments and corners of society becomes more bearable. The wealth generated by entrepreneurship finances the modern welfare state. The first generations of entrepreneurs in the industrial age tried to handle the redistribution function themselves. They contributed generously to churches and welfare causes - agencies often set up by or run by their wives and daughters. This system of private charity did a great deal of good but proved grossly inadequate

for the needs of a society in which more and more people left self- sufficient farms and became urban dwellers and workers in an entrepreneurial economy. Thus the welfare politicians entered the scene. It is worth stressing that entrepreneurship and social welfare in the affluent societies represent a sensible division of labor. The two are quite compatible, a fact that has been confirmed over and over again since the welfare concept was first enacted in Bismarck's Germany. The conflicts that do occur between entrepreneurs and welfare politicians come about when the latter use a flat rate of dole unrelated to performance in the labor market which kills motivation to work, instead of insured contracts. And, of course, when politicians impose a level of taxation that threatens to kill the goose that lays the golden egg. The most stupid thing politicians in the affluent society can do is to strangle the entrepreneurs to slow death by taxes.

In sum, the scope of entrepreneurship has been broadened by the trend from status to contract, and has not been seriously affected either by the modified contracts involved in unionization or by welfare politics. The threats come rather from two other sources: the decline in profit- based activities and the increased use of majority rule in place of entrepreneurial judgment.

If we, like the proverbial man from Mars, look at the big organizational structures on this earth we quickly discover that they fall into two classes:

This is a great divide in the man-made landscape. The future life of our planet depends very much on the balance between these two types of organizations. Roughly, they correspond to government and business. (But the correspondence is not entirely precise in all countries since there are government agencies that live on fees for the goods and services they provide and there are corporations with such a monopoly status that their prices are a kind of taxes.)(1) those that get their resources from taxation,

(2) those that get their resources from profits.

Opinion polls in the 1970s tell a story of declining confidence in government. In the United States this has been interpreted as a reflection of Vietnam and Watergate. But the same declining confidence in government is found in the other affluent countries of North America and Europe. (This trend, however, is not matched by an increased confidence in business.) There is reason to believe that the expansion of tax-based activities is near its peak in the Western countries. An extrapolation of current trends would make British, Dutch and Swedish taxes 100 per cent of GNP within some 30 or 40 years.

If we look at how decisions are made and justified in the big structures of today we find another great divide:

(1) decisions resulting from negotiations and justified by contracts,In the first instance a single person or group may enter a contract with many others and the contract is valid in spite of the fact that there are few on one side and many on the other. When majority rule applies, the will of the many decides over the few.(2) decisions resulting from voting and justified by majority rule.

An increasing number of decisions in the affluent countries are nowadays based on the majority principle, and the contractual principle is loosing ground, except perhaps for insured contracts. For example, in large organizations the employees are many and the employers few. There used to be and still is a straightforward hiring contract between employer and employee. However, we find increasing demands that varieties of majority rule and codetermination shall apply also in situations previously covered by contracts. In the name of majority rule, the labor unions act as if they held the places of work as fiefs. Trends in legislation in several countries regarding codetermination and union rights often support such claims.

Majority rule is a great achievement when applied to tax-based activities. No taxation without representation in the legislature, and no rule against the legislative majority. Such is the essence of political democracy and it should be honored and defended.

But should majority rule also apply in profit-based organizations? Here we must pause, and thoughtful men will reflect that there are obvious limits. The entrepreneurs and innovators thrive in a contractual society, and feel ill at ease if decisions about their life and work are made by a vote. Business decisions by majority rule also tend to be slow, cautious, and defensive, a far cry from the assertive risk—taking of the entrepreneurial spirit. To replace entrepreneurial judgments with majority decisions may drain business of dynamic qualities. For wherever majority rule applies the entrepreneurs tend to became outvoted by majorities of non-entrepreneurs. The entrepreneurial spirit, then, cannot perform its catalyzing role between labor and capital. To adopt the socialist solution and make labor the owner of capital is no remedy in this dilemma. For labor in the role of wage-earner normally gets the upper hand over labor in the role of guardian of capital.

If we combine the two dimensions we have delineated we obtain a fourfold table that more precisely defines the scope of entrepreneurship in affluent societies:

|

Decisions through negotiations: contracts |

Decisions through voting: majority rule |

|

| Resources from profits | A | B |

| Resources from taxation | C | D |

The A-sector is the traditional scope of entrepreneurship, and the D-sector is the traditional political democracy. The B- and C-sectors represent other elements. In C we find anything from public authorities (i e the hybrids of government and business that operate toll roads and bridges and also many ports and airports in the United States) and subsidized business of all kinds, to state capitalism. In B we find Maoist enterprises after the cultural revolution, Yugoslavian factories and other varieties of guild socialism as well as some versions of codetermined enterprises. It remains to be seen whether the spirit and morality of entrepreneurship can survive when fused with such encroaching elements from other sectors. The A-sector, the entrepreneurial territory par preference, is shrinking while all other sectors expand. The story seems to be the same in all affluent countries.

The Industrial Civilization started in England around 1770 and is only 200 years old. It has developed with unrivalled rapidity. The results are so impressive that one is apt to neglect any indication that the structure of Industrial Civilization is not built on unshakable foundations.

Few people realize how narrow the ranges are in the balance of forces - private, public, political, technological, educational, ideological - that have made the Industrial Civilization grow and prosper. While it lasts the balance of forces is rich in rewards. If or when it breaks down it will bring down the comfortable and exiting civilized life as we have learned to live it in the affluent countries. It is to the undying credit of the men who shaped the main parts of 19th and 20th centuries that they maintained the precarious balance of forces: allowing dynamic entrepreneurship to achieve growth and allowing humanitarian compassion to distribute the resulting welfare.

However, by not paying attention to the delicate balance of forces that favor entrepreneurship and innovation some of the affluent societies of today have probably come dangerously close to stagnation and actually face the threat of decline. For they refuse to recognize that the spirit of entrepreneurship and the climate of innovation are rare, if sturdy, plants in the human garden. Such plants do not sprout spontaneously but must be consciously cultivated in order to grow and survive. Political, educational, religious, and other institutions can promote or smother entrepreneurship. Politicians and educators of today - perhaps because of the success of the entrepreneurs and innovators - have tended to take them for granted. In affluent societies the entrepreneurs themselves now complain that the spirit of entrepreneurship and the climate of innovation are threatened by the spreading weeds of government regulations, the draining of resources by taxation, and the growing application outside the political realm of majority rule in place of entrepreneurial judgment. The critics of business argue that this is the usual griping of businessmen, and they are right in the sense that earlier generations of entrepreneurs expressed similar worries. But can we trust these critics to distinguish a gripe from a cry of a drowning man?

So far entrepreneurship in the affluent societies has weathered the storms and adjusted well to new conditions. But there are limits also to the amazing resilience of the entrepreneurs. The conditions of entrepreneurship should be studied more thoroughly and articulated wide and clear.