Speech delivered at the Swedish Chamber of Commerce for the United Kingdom, London, January 28, 1988.

The

interest on part of the international community in Swedish politics is

modest. Politically we are a dull

country, normally ruled by Social Democrats and/or Social Democratic ideas. The Social Democratic Labour

Party is a nearly 100-year-old party that has spun a tight network of public

services and auxiliary voluntary associations and unions into every corner of

the Swedish scene. In the past 56 years

the country has been ruled by Social Democrats during 50 years and by Social

Democratic ideas executed by non-socialist for six years.

Most

Swedes have been reasonably happy with this state of affairs. By carrying the country through the

depression of the 1930s, through World War II without getting involved in the

fighting, and through the post war boom, the ruling Social Democracy gained

considerable legitimacy. 44 years of holding the premiership, 1932 to 1976, is

a very long time in politics. It began

before Hitler and it ended after Mao. No wonder that for the Swedes --

including the opposition -- Social Democracy defines the terms and images of

politics. Every Swede is a little bit

of a Social Democrat, whether he or she likes it or not.

0O0

Olof Palme, the most well known and the most

controversial of the Social Democratic Premiers, was assassinated on February

28, 1986. He had attended a movie with

his family. He had brought no security

guards, nor any chauffeur-driven limousine. He was walking to the Stockholm metro to take the subway train back home

- three stops down the line. Like most Swedes, he lived an unassuming life,

void of ostentation, in this open, innocent and calm society (yes, you may say

it is dull).

The Swedes lacked both the psychological and

administrative preparedness for such an event. The assassination of a head of government was something they associated

with other parts of the world, not with Europe, and least of all with

Scandinavia. The police work was

scandalously poor and the assasin got away.

The site of the assassination at the corner of

Tunnelgatan and Sveavägen, one of Stockholm's main streets, quickly became a

place of pilgrimage, almost a shrine, to which people brought poems and roses.

The funeral of Olof Palme was not a state funeral in a

cathedral with officiating bishops and a coffin carried by generals. It was a party funeral that took place in

the Town Hall of Stockholm. The

pre-eminent symbols were the emblem of The United Nations, the plain white

coffin blanketed with red roses, and the hundreds of black-shrouded scarlet

banners of Sweden's workers' districts. The Social Democratic Party saw nothing wrong in this: it has dominated

Swedish politics for half a century and makes little distinction between itself

and the state.

The funeral was attended by heads of state and

dignitaries from all corners of the globe. They were seated in alphabetical,

not diplomatic order.

The funeral

represented a majestic tribute from supporters, opponents, and colleagues from

all over the world to the basic common denominator of values we share and to a

consensus about what constitutes a praiseworthy politician in our times. The Secretary of The United Nations

described Palme as "the quintessence of democratic man."

The

assassination of Olof Palme is the most important political event in the life

of the present parliament. The Social

Democratic Labour Party emerged revitalized from the crisis following the

assassination of Olof Palme. The party

surged ahead in the polls, and its new leader Ingvar Carlsson received a

confidence rating from the Swedish public that far surpassed any rating ever

received by the controversial Olof Palme.

oOo

There is no strong

spirit of opposition at hand in Sweden. Now and then, the ruling Social Democrats are accused of showing the

arrogance of power. For one thing, like

all (foolish) entrenched ruling parties, they use their power of appointment to

give most every leading post in the country to a party faithful. At present, however, unemployment is very

low, inflation is modest, the budget deficit is down. The mood of the land is that the Social Democrats will continue

to rule, and may even deserve to do so.

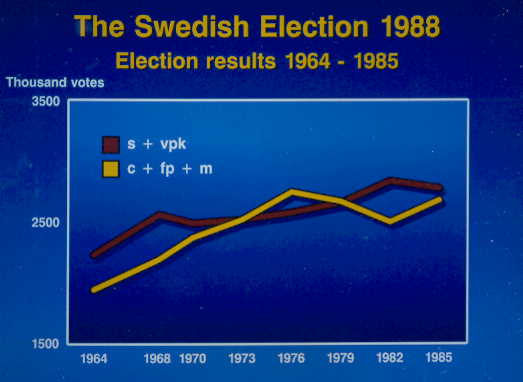

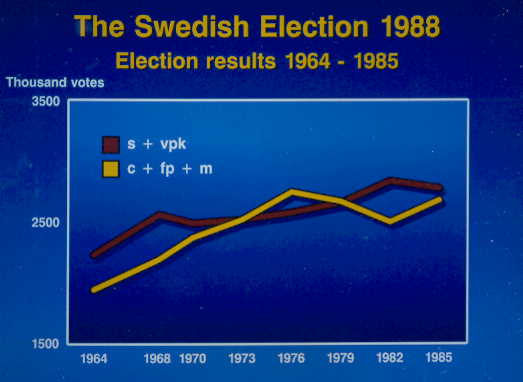

However, since 1964, there has emerged something like a British political rhythm: swings between the party of the left and the party of the right. (I am, of course, aware that Mrs. Thatcher has broken the normal rhythm by being re-elected a third time; such exceptions, however, do not cancel the main pattern of British political history.) In Sweden, a constitutional reform in 1970 abolished the upper house of Parliament and allowed such swings their full political consequences.

The socialist parties

in Sweden lost their majority i 1973 but continued to rule with a hung

parliament in which deadlocked issues were decided by the drawing of lots. In 1976, the non-socialists gained the

government for six years, that is, two election periods. In 1982 the socialists were back in power,

and they kept it with a reduced majority in 1985. Now, in the September election of 1988 we will find out whether

politics in Sweden is to remain a one-party affair like politics in Mexico or

Japan, or, to become a politics of alternating governments like Britain and the

Continent.

oOo

Political scientists

need not consider Swedish politics as dull. They can find their research stimulated by the fact that the Swedish

elections in the 1980s (along with the Danish) are the first ones in Western

Europe in which an absolute majority of the franchised derive their livelihood

from public funds. Sweden offers a

first-rate opportunity to study what happens when a country attempts to combine

the majority rule of democracy with such a large-scale public welfare so that a

majority is supported, in one way or another, by tax money.

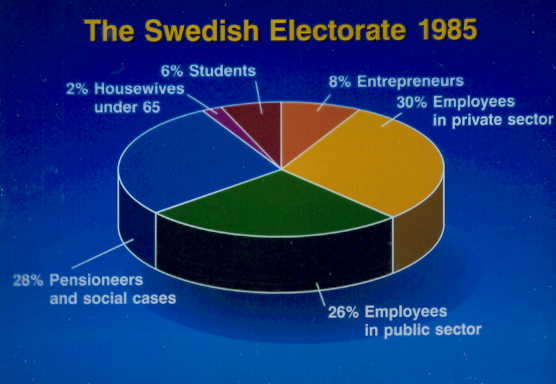

An absolute majority

of the 6.4 million enfranchised in the

Swedish elections of

the 1980s consists of those who are employed in the public sector or have their

primary source of income from the public coffers because of their entitlements

as pensioners, unemployed, chronically disabled, et cetera. Together, the "publicly supported"

constituted 52 percent of the voters in 1982, 54

percent in 1985 and 55 percent 1988 of the electorate.

Quite in line with these numbers is the Swedish tax

bite. Taxes constituted 51 per cent of GNP in 1982, 52 per cent in 1985 and 56

per cent in 1988. Needless to say, these rates are repeated world records of

taxation.

There, for the grace of God and Mrs. Thatcher goes

Britain, you may say.

The fathers of democracy never pondered such a

situation. The very thought that the

public sector would grow so large was beyond the horizons of their imagination.

Their reasoning was based

on the premise that the state with all its powers is in the hands of a minority

who are also living off the state. The

problem addressed by the fathers of democracy concerned the control this

minority. They devised democracy to

ensure that the ruling minority followed the will of the majority, who

naturally gained their livelihood in the private sector.

Sweden's problem has become the reverse: how shall a

minority who derive their incomes from the private sector protect themselves

against a publicly supported political bloc which not only represents a

majority of the electorate but can also draw upon all the sources of power

available to the state? And how is the

publicly supported plurality to guard against making decisions by majority rule

granting themselves favours that ruin the country?

In the early 1930s

the Social Democrats began the long process of casting the powers of the state

in the role of ally rather than adversary. Implementation of welfare was placed in public aegis, both the financing

and the administration.

The Social Democrats favoured public sector expansion

and they turned in due course the swelling ranks of the public employees into

their voting support. The old bourgeois civil service became a minority in most of the bureaucracies.

When those dependent

on public funds for their livelihood were in a minority, the Social Democrats

had great appeal with the promise that they would enlarge the welfare

system. This proved most effective and

resulted in the 44-year rule 1932 to 1976.

The 1982 election was

the first one in which the publicly supported constituted more than 50 per cent

of the electorate. Now, when those

supported by public funds are in a majority, the Social Democrats' appeal lies in

their promise to preserve the welfare system as it stands. This sufficed in 1982 to secure a working

majority in the Riksdag without any promises of new welfare reforms. In the 1985 election the power gained on

this basis was consolidated.

To the public at

large the party has portrayed itself as the defender of the rights of all

citizens to tax-financed benefits and services. Internally, to those employed

in the public sector or dependent upon it for their income, the Social

Democrats portray themselves as the party that will guarantee their jobs and

benefits.

This Janus face gives

the Social Democrats a mighty position in the public debate. On the one hand they have almost free rein

to tend to the selfish interests of the many employees and workplaces in the

public sector. At the same time they

can claim to be the party that cares for the well-being of the entire citizenry.

oOo

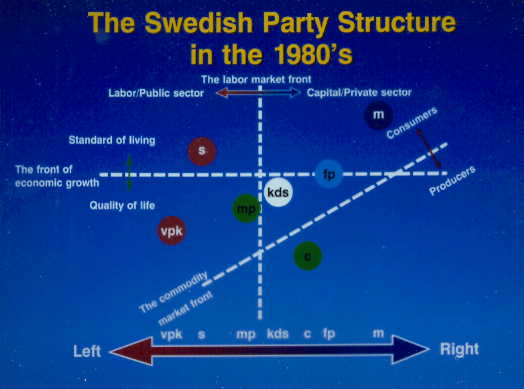

What is the party

structure that sustains this kind of politics?

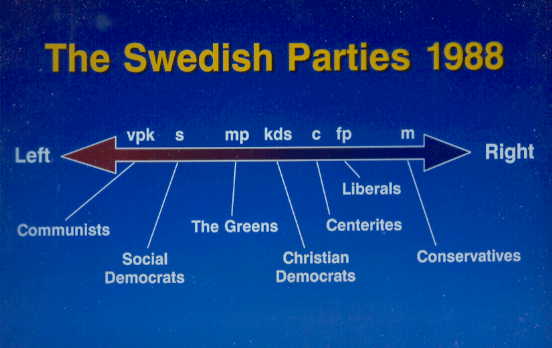

At stake in a Swedish

election - the next one is in September this year - is the manning of a truly

Big Government, albeit in a small state. The winners will directly control two

thirds of the GNP, and indirectly much of the remaining economy. The

incumbents, the Social Democratic Party

are designated (s). They are in the

main supported by Sweden's small Communist party (vpk).

The opposition

represents established bourgeois interests revitalized in the 1980s by the

Swedish counterpart to Thatcherite ideas, that is, neoliberal economic ideas of

our times and the revived moralism that calls for personal, family and network

responsibility rather than public welfare institutions. The opposition is split into four loosely

aligned parties: the Conservatives (m), the Liberals (fp), and the former Agrarians

called the Centerites (c), and the small Christian Democrats (kds).

The Constitution

excludes minor parties receiving less than 4 percent of the popular vote from

the Riksdag. By using a joint ticket

with a major party -- which is not unconstitutional in a technical sense -- a

minor party such as the Christian Democrats, got a seat in the 1985 Parliament

anyway. Such deals will not be repeated in 1988.

In the battle is also

an ecological party, the Greens (mp), which is expected to make progress this year,

and, according to the polls, for the first time gain seats in Parliament.

oOo

The simple scale of

the parties from left to right is a misleading guide to Swedish politics. In the Swedish multi-party system, the

parties' fight for votes is a war waged on all fronts. For a Liberal the struggle against the

Conservatives can be as important as that against the Social Democrats. For a Social Democrat the battle against the

Communists may seem as urgent as that against the Center Party. There are, however, three main frontlines in

the political battlefield of the 80s, and the parties may from time to time

variously join forces along these lines. The three fronts are the labour market, the commodity market, and

growth. The way the parties group themselves along

these fronts is illustrated in our diagram.

Most clashes occur

along the frontlines of the labour market. The struggle is for power over work

and the workforce, the production apparatus, and its surplus profits. The

frontline coincides with the preference for the private sector and the public

sector. The forces are aligned as follows:

Conservatives + Liberals + Centerites

against Social Democrats + Communists

This

frontline is the basis for the blocs in Swedish politics - the non-socialists

and the socialists, those who favour individual/entrepreneurial solutions and

those who favour collective/egalitarian solutions.

The other

front is the commodity market, primarily foodstuffs. The producers of

foodstuffs are in conflict with consumers. At the heart of the conflict are the

requisites conditions for primary industry and sparsely populated rural areas,

subsides to agriculture, and foodprices. The forces are aligned thusly:

Centerites

against Social Democrats + Communists + Liberals +

Conservatives

This front

is loosing importance; there are only 90.000 active farmers in the country. The

front is being redefined as periphery against the centre.

In

Swedish, Norwegian and Finnish history the farmers have never been serfs in a

feudal system. Thus we early had the

prerequisite for agrarian parties who organized the farmers while other parties

organized people in commerce and industry. The presence of the agrarian parties has split the bourgeois political

front in the Nordic countries and created the "Nordic decease of

politics": inability to oppose Social Democracy in a united way. The agrarian parties have often been ready

to enter compromises with the socialists, or enter coalition governments with

them. Only when the Swedish Centerites

in 1976 turned against the nuclear energy policy of the Social Democrats could

the latter be defeated.

The third

frontline is growth. The fight is between supporters of economic growth and

quality of life. It concerns the environment, large-scale industry, elaborate

bureaucracy, and heavy dependence on exports, decentralization. The forces are

aligned thusly:

Centerites

+ Communists + Greens against Liberals

+ Social Democrats + Conservatives

We

recognize this front from the 1980 referendum on nuclear energy. There are

indications of other minor frontlines. One would be the religious front, where KDS, the Christian Democratic

Socialists, stand-alone against all other parties, with the possible exception

of the Centre Party. Yet another would

be foreign affairs: APK, the Workers' Communist Party, is Stalinist and loyal

to the Soviet Union through thick and thin, and stands in opposition to all

other parties, particularly the Conservatives are viewed as more friendly to

the United States than others. In

contrast to many other countries, Swedish party structure does not evince any

marked alignment along cultural-ethic lines.

The

Green party is quality-of-life oriented, is more non-socialist than socialist,

and differs from the Centre party in that it is more concerned with the

consumer than with the producer.

oOo

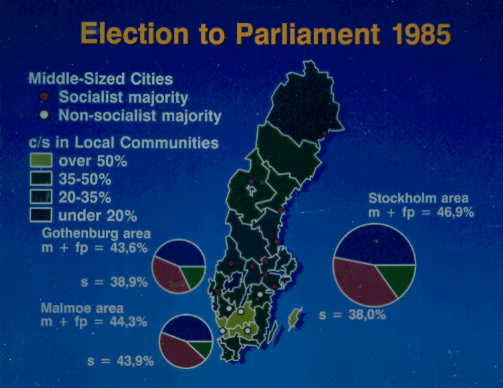

The regional election

trends show the Conservatives and Liberals jointly dominating the three

metropolitan regions of the country. In

the Stockholm, Gothenburg and Malmoe area they are bigger than the Social

Democrats. Centerites and Communists in

these areas are environmental parties, as are the Greens.

In the middle-sized

cities in the southern third of the country the non-socialists rule. (The

pattern is similar to England south of Manchester.) In the northern cities the

socialists rule.

In the

periphery, or country side, the battle rages between Centerites and Social

Democrats. The Centerites are strong in two bands across the country, from

Halland to Gotland in the south, and in Jämtland in the north.

oOo

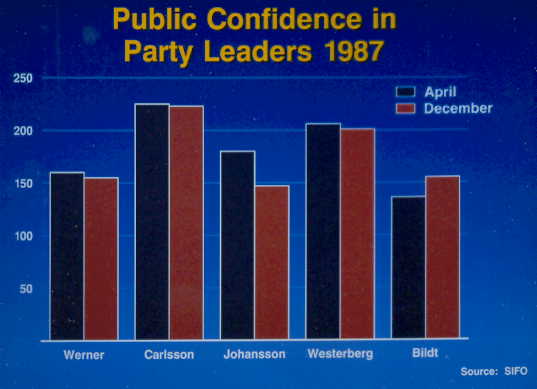

It so happens that

all parties in parliament except the Communists have new leaders. The Liberals

shifted to Bengt Westerberg prior to the last election, the others go into the

campaign with entirely new leaders. All parties have chosen experts as leaders.

Gone are the great gamesmen such as Palme (s) and Adelsohn (m) and Fälldin (c),

the helper

and facilitator Karin Söder (c). In came the knowledgeable men from middle

management and staff, men with facts and statistics but without classical

education, global experience, or practical knowledge that can only be gained

from the leadership of large, complex organizations.

Public

confidence in these men varies.

By a large

margin, the Social Democratic and the Liberal leader are in top.

oOo

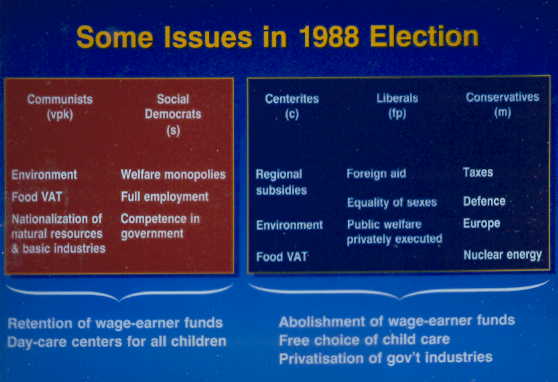

The size and

pervasiveness of the body politic in Swedish society make for many political

issues and is in itself an issue in the political debate.

The issues of the 1988 election are

illustrated in this chart.

Free

choice of subsidized child care is one of the issues that joins the three

non-socialist parties in this election. It is the first time that the

non-socialists have a popular welfare issue and the Social Democrats stand for

an unpopular issue.

oOo

To what does this all

add up? I have asked my computer.

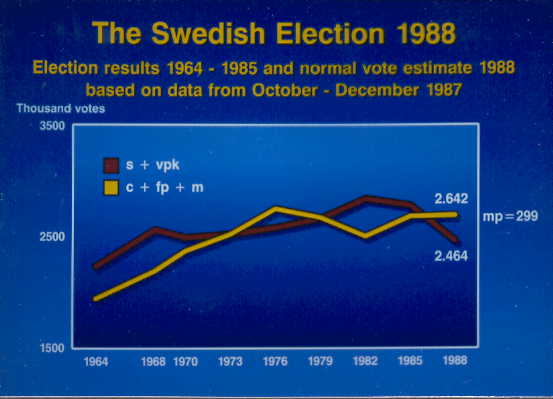

If the 1988 election

runs a normal course without unforeseen upsets, our calculations indicate that

the non-socialist bloc will resume the pattern it evinced between 1964 and 1976

prior to the disappointments with the Fälldin governments of growing at a

faster rate than the socialist bloc. The period 1982-85 began this tack. This would make for a close election, not

uncommon in Sweden. The odds, as I

calculate them at this early stage, are, however, in favour of the non-socialists, but with the

prospect that the

Greens will hold the balance of power in Parliament.

Green

parties tend to use parliaments as stages for political theatre rather than

political compromise. Thus I predict a weak

and unstable government in Sweden after this fall's election. We get a shift in government, a normal

European swing between left and right, but at the price of instability and

political inexperience.

That is

the end of my tale. Thank you very much!